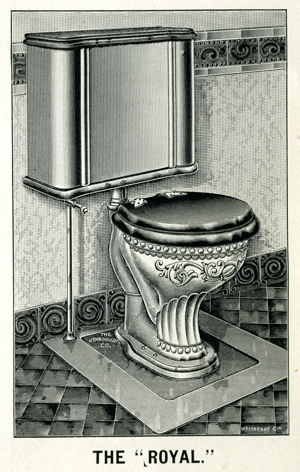

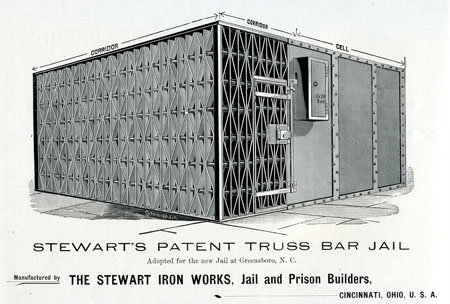

The image above comes from the same publication I mentioned in my previous post on jail construction. While I’ll let the image and name of the device speak for itself, I do wonder if these were also installed in the Greensboro jail. Somehow, I doubt it.

Month: December 2008

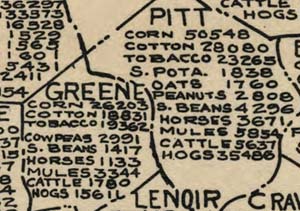

1921 Crop Map

There is an interesting map on the North Carolina Maps site showing the agricultural output of North and South Carolina in 1921. Listing livestock and crop production by county, the map demonstrates the richness and variety of farm activities in the state. The map shows heavy yields of tobacco, sweet potatoes, and peanuts in the eastern part of the state, while wheat, oats, and rye were grown out west. Cattle and hogs show up just about everywhere.

There is an interesting map on the North Carolina Maps site showing the agricultural output of North and South Carolina in 1921. Listing livestock and crop production by county, the map demonstrates the richness and variety of farm activities in the state. The map shows heavy yields of tobacco, sweet potatoes, and peanuts in the eastern part of the state, while wheat, oats, and rye were grown out west. Cattle and hogs show up just about everywhere.

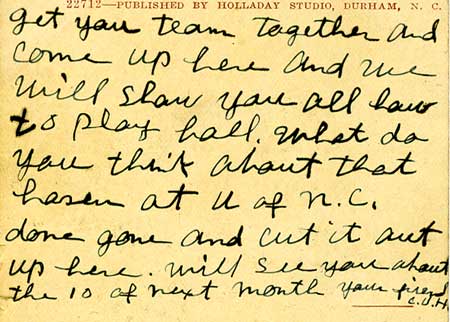

Isaac William Rand Hazing Incident

I don’t mean to dwell on postcards, but you really do find some amazing things on both sides of them. Most of our blog entries have focused on the image side, but some have examined the messages found on the cards. As I was editing a recent batch, I noticed the following message on a postcard from Oak Ridge Military Institute:

“get your team together and come up here and we will show you all how to play ball. What do you think about that hasen at U of N.C., done gone and cut it out up here. Will see you about the 10 of next month your friend C.U.H.”

The postcard is postmarked 18 September 1912. Something about “hasen” [hazing] and September of 1912 sounded very familiar…and then it hit me: the Isaac William Rand hazing incident.

For those of you that have not heard of this, a short version of the story from our “This Day in the History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill” website is below:

“September 13, 1912:

Isaac William Rand, a freshman from Smithfield, died in an early morning hazing incident. After falling from a barrel and cutting his jugular vein on a broken bottle, he quickly bled to death. Four sophomores were dismissed from the University for the episode, and they were later arrested by Orange County officials. After the trial, one was acquitted of any wrongdoing and three were found guilty of manslaughter.”

For more information on this incident, visitors to the North Carolina Collection can view Materials pertaining to the hazing death of Isaac William Rand, 1912 / compiled by Jerry W. Cotten.

Jail Construction

I have to admit that I’ve never really thought about how a jail or prison was constructed…other than my January 2007 “This Month in North Carolina History” on the construction of the North Carolina State Penitentiary. Still, I didn’t give a lot of thought to how the individual cells were constructed. Well, I still can’t speak intelligently on the subject, but I do have this nice image to show! This ad is found in a book of architectural plans from ca. 1898-1900. Hey, if it was good enough for the Greensboro jail, it’s good enough for me.

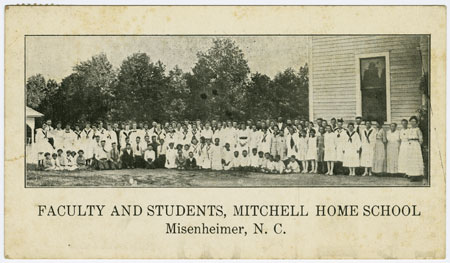

New Towns On NC Postcard Site

The North Carolina Postcard site now has a postcard from Misenheimer and Pine Level, two NC towns that were not on the site before. Check them out!

Jonkonnu In North Carolina

Have you ever heard of “Jonkonnu”? No? Well, you can check out Harry McKown’s most recent edition of “This Month in North Carolina History” for the details.

December: Jonkonnu in North Carolina

This Month in North Carolina History

In antebellum North Carolina, Christmas season was the time for an African American celebration found almost nowhere else in North America, but widespread through the islands of the Caribbean. Variously called Jonkonnu, Johnkannaus, John Coonah, or John Canoe, the custom was described in the slave community of Jamaica in the late eighteenth century where it was thought to have been of African origin. Although the details often changed from place to place, Jonkonnu usually involved several African American men who dressed in costumes made of rags and animal skins with grotesque masks and horns. Sometimes one of their number wore his best clothes instead. They danced wildly, often playing musical instruments and singing. In towns, the Jonkonnu men went from house to house while on plantations they performed at the homes of masters, overseers, and other white people. They expected to be rewarded with gifts of money or liquor. Jonkonnu dancers were often accompanied by crowds of men and women who cheered them on while taking no direct part in the performance.

Jonkonnu obviously represented a time of release and enjoyment for slaves from the drudgery of their day–to–day work. Some historians believe that it may also have been a time when the constraints of the slave system were loosened in other ways. On plantations in North Carolina slaves of all sorts had access to their masters in ways that they seldom had during the year. The Jonkonnu performers and their accompanying crowd usually came right up to their master’s house, a privilege usually denied to all but house servants. After the performance, the master would often speak to the performers and shake hands with them, another departure from usual practice. Jonkonnu continued in North Carolina after emancipation, at least in Wilmington, where it was observed as late as 1880. A version of it also seems to have been adopted by whites in the late nineteenth century. In the end, however, it may have been too closely tied to the slave system in which it arose to have survived long after freedom.

Sources

Fenn, Elizabeth A. “‘A perfect equality seemed to reign’: Slave Society and Jonkonnu.” The North Carolina Historical Review, 65:2 (April 1988), pages 127-153.

Powell, William S., Ed. The Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, c. 2006