This Month in North Carolina History

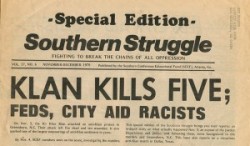

On November 3, 1979, members of the Communist Workers Party (known then as the Worker’s Viewpoint Organization) sponsored a rally at Morningside Homes, a housing project in Greensboro. Billed Klan Kills Five Headlineas a “Death to the Klan Rally,” the demonstrators gathered to speak out against what they saw as continued racial injustice in North Carolina.

A group of self-proclaimed Klansmen and Nazis attended the rally and fired upon the crowd, killing five people and wounding nine. Much of the violence was captured on film by reporters who were covering the event.

The men accused of firing on the crowd were apprehended and charged with murder. In November 1980 a jury found them not guilty on the grounds of self-defense. After extensive FBI inquiries into the killings, the case was reopened and, in 1983, nine people were indicted for conspiracy to violate the protesters’ civil rights. Again, the defendants were acquitted.

In addition to their outrage at the violence in their community, many people in Greensboro blamed the police department for failing to act promptly enough to prevent the killings. The frustration in the community continued to grow as the courts failed to convict anyone for the shootings.

At the twentieth anniversary of the killings in 1999, it was clear that tensions in Greensboro still ran high and that there were many unresolved feelings and accusations surrounding the case. A Truth & Reconciliation Commission, modeled on similar projects in South Africa, was established in 2004. The Commission began holding public hearings on the 1979 killings, operating under the principle that the community cannot begin to heal until the events of the past are honestly and openly confronted. The final report of the Commission is due in 2006.

Sources

Elizabeth Wheaton, Codename GREENKIL: The 1979 Greensboro Killings. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987.

“The Third of November.” Southern Exposure, vol. 9 no. 3 (Fall 1981), pp. 55-67.

Greensboro Truth & Reconciliation Commission

http://www.greensborotrc.org/

Greensboro Truth & Community Reconciliation Project

http://www.gtcrp.org/ (available via the Wayback Machine)

Image Source:

Southern Struggle (Special Edition), vol. 37 no. 6 (November-December 1979). Greensboro Massacre Materials, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“They Died Fighting Rather Than Live As Slaves.” Card produced by the Committee to Avenge the Greensboro-CWP 5, [1979]. Greensboro Massacre Materials, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

We’ve recently discussed a couple of North Carolinians — George Badger and John J. Parker — who failed to be confirmed by the Senate after being nominated for the Supreme Court. We should point out that not every Tar Heel proposed for the Court has met with this fate. It’s just been a little while since one of our fellow North Staters has been confirmed. James Iredell was the first Supreme Court Justice from North Carolina, serving on the court from 1790-1799. After the death of Iredell, New Hanover County native Alfred Moore was nominated by President John Adams and confirmed by the Senate. Moore sat on the Court until 1804.

We’ve recently discussed a couple of North Carolinians — George Badger and John J. Parker — who failed to be confirmed by the Senate after being nominated for the Supreme Court. We should point out that not every Tar Heel proposed for the Court has met with this fate. It’s just been a little while since one of our fellow North Staters has been confirmed. James Iredell was the first Supreme Court Justice from North Carolina, serving on the court from 1790-1799. After the death of Iredell, New Hanover County native Alfred Moore was nominated by President John Adams and confirmed by the Senate. Moore sat on the Court until 1804.

“While there may be some question as to who should be regarded as the greatest North Carolinian, certainly in a list of the five greatest, the name of George E. Badger should be included.”

“While there may be some question as to who should be regarded as the greatest North Carolinian, certainly in a list of the five greatest, the name of George E. Badger should be included.” Whenever we walk through the county history section in the North Carolina Collection, one book always catches our eye. Most hardcover books used to be bound in cardboard which was then covered with cloth (many still are today, though more and more publishers go simply with the board covers). When it came time to bind Walter Whitaker’s Centennial History of Alamance County, 1849-1949, they probably didn’t have to think very hard about what kind of cloth to use.

Whenever we walk through the county history section in the North Carolina Collection, one book always catches our eye. Most hardcover books used to be bound in cardboard which was then covered with cloth (many still are today, though more and more publishers go simply with the board covers). When it came time to bind Walter Whitaker’s Centennial History of Alamance County, 1849-1949, they probably didn’t have to think very hard about what kind of cloth to use.