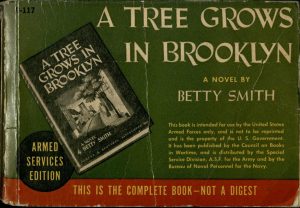

During WWII, keeping up morale for American soldiers was a major national concern. The Library Section of the U.S. War Department, and later an organization called the Council on Books in Wartime, figured out a way to print contemporary titles inexpensively in a small paperback format that would also be easy to carry. The books were printed on presses used for magazines, so the text was set in two columns and each printed page usually included the text of four books. Once printed, the pages were cut apart horizontally. This process created paperbacks that were wider than they were tall. The covers of the Armed Services Editions (ASE) showed an image of the original book cover and noted whether the edition was abridged. Most were not.

Over the course of the war, 1,322 books (some of which were reprints) were selected to be Armed Service Editions. The list of titles comprised many genres and styles, including fiction, nonfiction, plays, and poetry. It included contemporary literature as well as classics. Though the Army and Navy had to approve the titles selected by the Council on Books in Wartime, there was much less censorship of the titles than might be expected. The program handed out more than one million copies of ASE paperbacks, each free to service members.

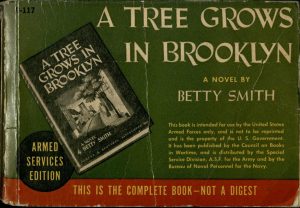

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Armed Services Edition

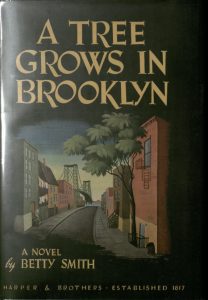

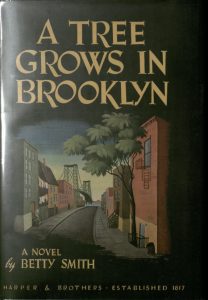

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, standard edition

One of the books chosen for publication as an ASE was Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Smith worked for years as a playwright before writing her first novel, which was wildly successful. She wrote A Tree Grows in Brooklyn while living in Chapel Hill, but based the novel on her childhood in Brooklyn. This story of a young girl growing up in the tenements was surprisingly popular with soldiers, who sent lots of fan mail to Betty Smith in Chapel Hill. According to Michael Hackenberg’s “The Armed Services Editions in Publishing History,” Smith actually received much more fan mail from soldiers than she did from civilians, even though her book was very popular at home.

Because of its popularity, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was one of about 100 titles chosen for a second printing as an ASE. In their fan letters, some soldiers wrote that Smith’s book reminded them of their own childhoods in Brooklyn.

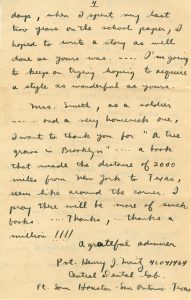

Letter to Betty Smith from September 23, 1944, Betty Smith Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library

In a fan letter dated September 5, 1944, Charlie Pierce wrote, “I am a soldier some 1,500 miles from my beloved Brooklyn of which you wrote, so I know something of loneliness. Your book brought many hours of happiness to me – it was so human and so understanding.” Yet another soldier, Frank Ebey, called it simply, “that splendid book,” in his letter from September 1944. Perhaps it was the humanity that Pierce notes, more than a sense of place, which caused A Tree Grows in Brooklyn to resonate with so many ASE readers.

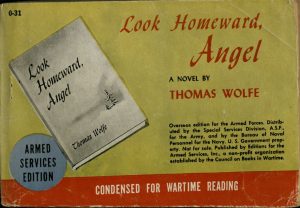

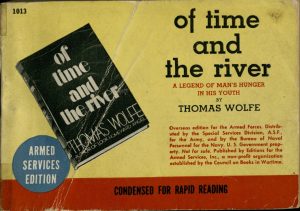

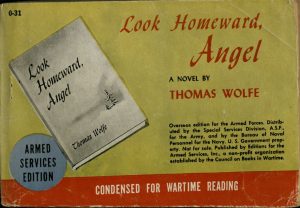

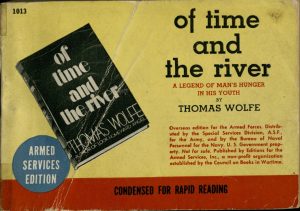

Betty Smith was not the only author with North Carolina ties to have a work published as an ASE. The program printed two of Thomas Wolfe’s novels, Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River.

Look Homeward, Angel, Armed Services Edition

Of Time and the River, Armed Services Edition