The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission has just released a draft of its report on the violent uprising that ravaged Wilmington’s African American community in November 1898. The Commission was organized under legislation sponsored by two Wilmington legislators and charged with examining and reporting on what is now widely acknowledged to be the only coup d’etat in American history. Today’s Raleigh News & Observer and Wilmington Star-News have stories about the report’s findings.

Category: History

Presidents in Kernersville

Most of the media reports of President Bush’s speech yesterday in Kernersville noted that it was the first presidential visit in the town since George Washington passed through in 1791.

Washington visited North Carolina on his tour of the southern states in the spring and summer of 1791, as part of his plan to visit every state in the union during his term in office. We know about his visit to Kernersville from an entry in his diary for June 2, 1791. Washington’s party was traveling from Salem, where he had spent several days, to Guilford, where he was to visit the site of the Revolutionary War battle of Guilford Courthouse. Washington wrote,

“In company with the Govr. I set out by 4 Oclock for Guilford — Breakfasted at one Dobsons at the distance of eleven Miles from Salem . . . .”

The “one Dobson’s” was Dobson’s tavern, located at Dobson’s crossroads, at the site of what would later become the town of Kernersville (incorporated 1871). Sadly, there is no mention in the diary of what was served.

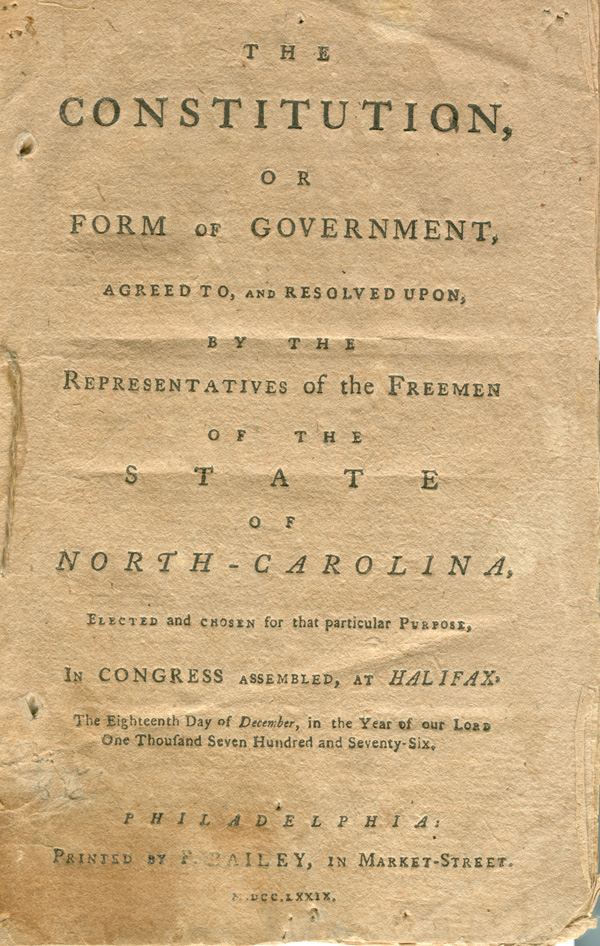

December 18, 1776: North Carolina Constitution

This Month in North Carolina History

News that the American colonies had declared independence from Great Britain finally reached North Carolina on July 22, 1776. One of the first orders of business in the newly independent state was the writing of a constitution. Elections for the Provincial Congress were held in October and, once elected, the representatives met in Halifax. Several states had already adopted constitutions, and North Carolina looked to these as examples. The legislators also examined the English Declaration of Rights and wrote to John Adams for advice. Rather than go through the lengthy and uncertain process of submitting the document to the voters, the representatives agreed that once they approved the final draft, it would be enacted. On December 18, 1776, North Carolina had its first constitution.

News that the American colonies had declared independence from Great Britain finally reached North Carolina on July 22, 1776. One of the first orders of business in the newly independent state was the writing of a constitution. Elections for the Provincial Congress were held in October and, once elected, the representatives met in Halifax. Several states had already adopted constitutions, and North Carolina looked to these as examples. The legislators also examined the English Declaration of Rights and wrote to John Adams for advice. Rather than go through the lengthy and uncertain process of submitting the document to the voters, the representatives agreed that once they approved the final draft, it would be enacted. On December 18, 1776, North Carolina had its first constitution.

The 1776 North Carolina Constitution has many elements that will seem familiar to North Carolinians today. The Constitution opens with a Declaration of Rights, containing twenty-five guarantees of personal freedom that anticipate the Bill of Rights in the United States Constitution and many of which are present in similar form in the current state constitution. The first North Carolina constitution also presents a familiar form of government, with a governor and a bicameral legislature.

However, there are several sections that differ significantly from current practice. The most notable of these were the property requirements for officeholders and voters. In order to be eligible for the Senate, members had to own at least three hundred acres of land in the county they sought to represent; candidates for the House of Commons were required to own one hundred acres; and voters were required to own at least fifty acres to be eligible to cast a ballot for a senator.

Under the 1776 constitution, most of the power was vested in the General Assembly. Governors were chosen by the legislature, served only a one-year term, and were not eligible to serve more than three terms in a six year period. Legislators were appointed by county (with a few assigned to specific towns), without regard to population. This vested a disproportionate amount of influence in the eastern part of the state, which had many small counties, even though the western counties began to increase steadily in population.

The 1776 constitution was effective in establishing an independent government in North Carolina and guaranteeing individual liberties for its citizens. Yet under this document, the state remained in the control of a small group of primarily eastern elites. North Carolina grew slowly, on its way to earning the nickname “The Rip Van Winkle State” in the early nineteenth century. By overlooking many of the demands of its less prosperous citizens, North Carolina saw a widespread emigration and was finally forced to draft a more egalitarian constitution. The state passed a series of amendments in 1835 that changed to a system of representation that was determined by population and allowed for the popular election of the governor. It was not until after the Civil War, in 1868, when North Carolina finally adopted a constitution that did not include property requirements for officeholders.

Sources:

William S. Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

John L. Sanders, “A Brief History of the Constitutions of North Carolina.” In North Carolina Government 1585-1979: A Narrative and Statistical History. Raleigh: North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State, 1981.

“Constitution of North Carolina: 18 December 1776.” Avalon Project, Yale Law School, http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/states/nc07.htm

Image Source:

The Constitution, or Form of Government, Agreed to, and Resolved Upon, by the Representatives of the Freemen of the State of North Carolina. Philadelphia: Printed by F. Bailey, 1779.

Our First State Constitution

The December This Month in North Carolina History feature looks at North Carolina’s first state constitution, adopted on December 18, 1776.

Chicken Dispute

As a service to our readers, we want to point out that the North Carolina General Assembly has just amended the state law on cockfighting. As of today, “[a] person who instigates, promotes, conducts, is employed at, allows property under his ownership or control to be used for, participates as a spectator at, or profits from an exhibition featuring the fighting of a cock is guilty of a Class I felony.” Previously, guilty persons were charged only with a Class 2 misdemeanor.

Long gone are the days when the fighting cocks of North Carolina were a matter of state pride. In B.W.C. Roberts’s article, “Cockfighting: An Early Entertainment in North Carolina” (North Carolina Historical Review, July 1965), we learned about the great battle between North Carolina and South Carolina in Wilmington in 1896. At the three-day match, called a “main,” the North Carolina cocks prevailed, nine to three. We checked the Wilmington Morning Star for May 8, 1896, to see how much attention the fights received in the local press. It was indeed front page news, though it warranted only a single, somewhat droll paragraph under the “Local Dots” section:

“A chicken dispute has been going on for the past three days about a half mile from the city limits on the Princess Street road, between North Carolina and South Carolina, the North Carolina birds winning the main.”

North Carolina Lottery

With a new state lottery about to begin, we decided to have a look at Alan D. Watson’s article, “The Lottery in Early North Carolina” (North Carolina Historical Review, October 1992) to see how it worked a few centuries ago.

Watson pointed us to the early laws of North Carolina, which contained a provision for a lottery as early as 1760. The act allowed four Managers to organize a lottery to raise money to finish the construction of churches in Wilmington and Brunswick. It was noted that an earlier lottery had been tried but failed due to “the Scarcity of Proclamation Money in this part of the Province.” The new act allowed players in the lottery (referred to as “adventurers”) to buy tickets with only a written promise of payment. The price for the ticket was pretty steep for a somewhat meager payment, at least by PowerBall standards. For three pounds, you could purchase a ticket giving you a chance at a grand prize of four hundred pounds. In order to supplement the money raised by the lottery, the state would also allow the churches to use money obtained from the sale of slaves captured from a wrecked Spanish privateer.

Tar Heels on the Supreme Court

We’ve recently discussed a couple of North Carolinians — George Badger and John J. Parker — who failed to be confirmed by the Senate after being nominated for the Supreme Court. We should point out that not every Tar Heel proposed for the Court has met with this fate. It’s just been a little while since one of our fellow North Staters has been confirmed. James Iredell was the first Supreme Court Justice from North Carolina, serving on the court from 1790-1799. After the death of Iredell, New Hanover County native Alfred Moore was nominated by President John Adams and confirmed by the Senate. Moore sat on the Court until 1804.

We’ve recently discussed a couple of North Carolinians — George Badger and John J. Parker — who failed to be confirmed by the Senate after being nominated for the Supreme Court. We should point out that not every Tar Heel proposed for the Court has met with this fate. It’s just been a little while since one of our fellow North Staters has been confirmed. James Iredell was the first Supreme Court Justice from North Carolina, serving on the court from 1790-1799. After the death of Iredell, New Hanover County native Alfred Moore was nominated by President John Adams and confirmed by the Senate. Moore sat on the Court until 1804.

Iredell is the subject of a recent biography by Willis P. Whichard (Justice James Iredell, published by Carolina Academic Press, 2000). There is still no full-length biography of Moore, but interested readers can look to a shorter sketch by Robert Mason, Namesake: Alfred Moore, 1755-1810, Soldier and Jurist, published by the Moore County Historical Association in 1989.

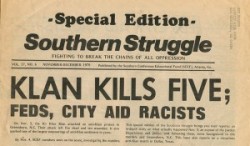

November 1979: Greensboro Killings

This Month in North Carolina History

On November 3, 1979, members of the Communist Workers Party (known then as the Worker’s Viewpoint Organization) sponsored a rally at Morningside Homes, a housing project in Greensboro. Billed Klan Kills Five Headlineas a “Death to the Klan Rally,” the demonstrators gathered to speak out against what they saw as continued racial injustice in North Carolina.

A group of self-proclaimed Klansmen and Nazis attended the rally and fired upon the crowd, killing five people and wounding nine. Much of the violence was captured on film by reporters who were covering the event.

The men accused of firing on the crowd were apprehended and charged with murder. In November 1980 a jury found them not guilty on the grounds of self-defense. After extensive FBI inquiries into the killings, the case was reopened and, in 1983, nine people were indicted for conspiracy to violate the protesters’ civil rights. Again, the defendants were acquitted.

In addition to their outrage at the violence in their community, many people in Greensboro blamed the police department for failing to act promptly enough to prevent the killings. The frustration in the community continued to grow as the courts failed to convict anyone for the shootings.

At the twentieth anniversary of the killings in 1999, it was clear that tensions in Greensboro still ran high and that there were many unresolved feelings and accusations surrounding the case. A Truth & Reconciliation Commission, modeled on similar projects in South Africa, was established in 2004. The Commission began holding public hearings on the 1979 killings, operating under the principle that the community cannot begin to heal until the events of the past are honestly and openly confronted. The final report of the Commission is due in 2006.

Sources

Elizabeth Wheaton, Codename GREENKIL: The 1979 Greensboro Killings. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987.

“The Third of November.” Southern Exposure, vol. 9 no. 3 (Fall 1981), pp. 55-67.

Greensboro Truth & Reconciliation Commission

http://www.greensborotrc.org/

Greensboro Truth & Community Reconciliation Project

http://www.gtcrp.org/ (available via the Wayback Machine)

Image Source:

Southern Struggle (Special Edition), vol. 37 no. 6 (November-December 1979). Greensboro Massacre Materials, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“They Died Fighting Rather Than Live As Slaves.” Card produced by the Committee to Avenge the Greensboro-CWP 5, [1979]. Greensboro Massacre Materials, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Greensboro Killings, 1979

The latest This Month in North Carolina History feature looks at the events of November 3, 1979, when members of the Communist Worker’s Party clashed with the Ku Klux Klan in Greensboro. The current work of groups like the Greensboro Truth & Reconciliation Commission reminds us that our history is more than dry details and dates relegated to textbooks, that in fact it is a vital part of the world we live in today.

George Badger

“While there may be some question as to who should be regarded as the greatest North Carolinian, certainly in a list of the five greatest, the name of George E. Badger should be included.”

“While there may be some question as to who should be regarded as the greatest North Carolinian, certainly in a list of the five greatest, the name of George E. Badger should be included.”

We’ll bet he wasn’t on your list. That quote, and the portrait, are from volume seven of Samuel Ashe’s Biographical History of North Carolina, published in 1908. Badger (1795-1866), a native of New Bern, held a number of government posts, including Secretary of the Navy under William Henry Harrison. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1846.

We ran across Badger in researching North Carolinians who had been nominated to the Supreme Court. In 1853, President Millard Fillmore nominated Badger to fill a seat left vacant by the death of Justice John McKinley. The discussion over Badger’s nomination focused on his views on a strong federal government and slavery. Southern, pro-slavery Democrats ultimately turned against Badger, a Whig, and his nomination was defeated by a vote of 26-25. After leaving the Senate in 1855, and with the demise of the Whig party, Badger did not hold another prominent position in government.