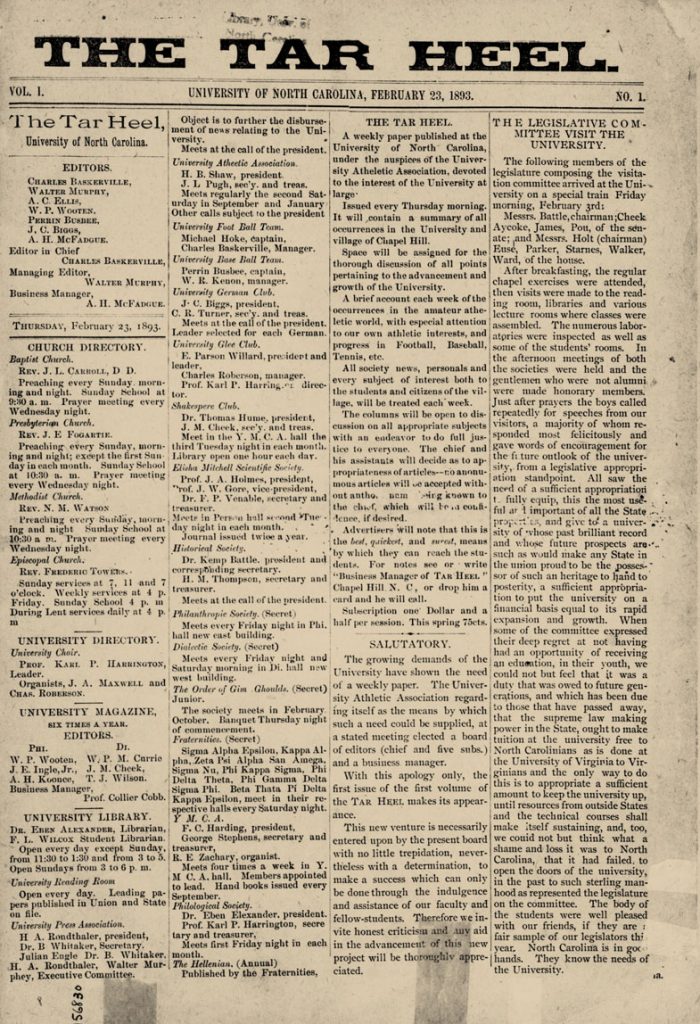

This what if began with a question found in the December 6, 1877 edition of The Farmer and Mechanic, a weekly paper published in Raleigh. Dr. W. Haw, an “analytical chemist” of Oswego, N.Y., wanted to know whether the poppy species that yields opium could be planted in the South.

I resided a long time in the East Indies, and cultivated opium near Patva, and I should think the Southern States favorable therefor (sic). I should like to engage in the business, if possible. The question is—is the opium of the South strong enough, has it proper medical qualifications, and is the yield favorable.

A search of subsequent editions of The Farmer and Mechanic yielded no answer to Haw’s inquiry. The question remained. These days North Carolina is home to numerous experiments with “specialty crops.” Tar Heels are growing truffles, hops, edamame and wasabi. Did anyone ever try growing papiver somniferum, the Latin name for the poppy species that yields opium and its medicinal derivatives as well as the seeds that coat a popular type of bagel?

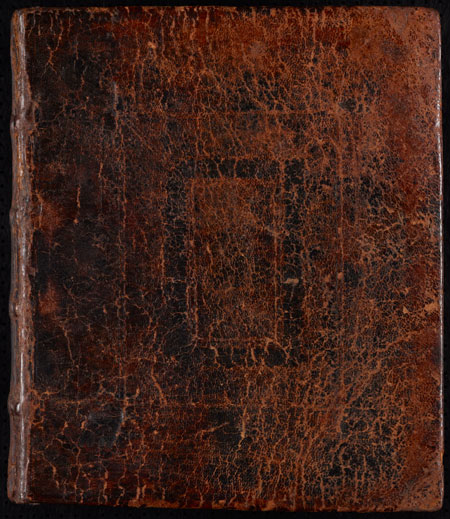

A search of the North Carolina Collection stacks produced a paper written by Thomas Williams Kendrick to fulfill requirements toward his graduate degree in pharmacy from UNC in 1899. His paper, with the simple title “Opium,” details the history of opium use and poppy cultivation through time, leading the reader through Moghul India, royal courts in Europe and 19th-century China. Kendrick, who, upon leaving UNC, worked as a pharmacist in the southwest Piedmont of N.C., then notes:

During the last two years of the Civil War, R.W. Price, M.D. (Cleveland County, N.C.) cultivated the poppy and gathered enough to supply the needs of his patients until some time after the close of the war. He considered the opium superior to that obtained from the markets. The drug was collected in the usual way by making several incisions in the capsule and collecting the concrete juice on the following morning.

Kendrick offers no other details on Price or his poppy cultivation. He attributes the information to correspondence with someone in Grover, N.C., a town in Cleveland County, in November 1898. A search of Cleveland County histories and records suggests that the Price to whom Kendrick referred may have in fact been Reynolds Bascomb Price (that’s R.B. Price, rather than R.W. Price), a man born in 1826 who practiced as a physician in Grover for many years. Price was an 1844 graduate of Davidson College and died in 1907. But, alas, he appears to have left no account of his life, particularly his experiments with poppy cultivation and opium production.

Kendrick also cites information from Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural, a volume by Francis Peyre Porcher, a South Carolina physician. Porcher taught at the Medical College of South Carolina for many years during the second half of the 19th century. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined the Confederate Army as a surgeon and served mostly at hospitals in Norfolk and Petersburg, Virginia. Midway through his Confederate service, Porcher was released from his hospital duties to work on a handbook about local plants with therapeutic qualities that could be used by Confederate doctors as well as Southern planters and farmers in place of manufactured drugs that were unobtainable because of the Union blockade. Resources of the southern fields and forests,…. was initially published in 1863 and subsequently republished several times because of its valuable information.

Porcher devotes 5 1/2 pages to papaver somniferum. He quotes from several European authors describing poppy cultivation as well as a U.S. Patent Office report for 1855, which notes that cultivation of poppies for opium is “an object worthy of public encouragement, as the annual amount of opium imported into the United States is valued at upward of $407,000.” Porcher writes that his own experiments on “specimens of the red poppy found growing in a garden near Stateburgh, S.C.” yielded more than “an ounce of gum opium, apparently of very excellent quality, having all the smell and taste of opium (which I have administered to the sick)….” He adds:

I have little doubt that all we required could be gathered by ladies and children within the Confederate States, if only the slightest attention was paid to cultivating the plants in our gardens. It thrives well, and bears abundantly. It is not generally known that the gum which hardens after incising the capsules is then ready for use, and may be prescribed as gum opium, or laudanum and paregoric may be made from it, with alcohol or whisky.

Some 40 years after Porcher’s experiments, Edward Vernon Howell began cultivating poppies. Howell was a Raleigh native whom UNC president Edwin A. Alderman hired in 1897 to revive the moribund School of Pharmacy at the University. During his 30 year association with the pharmacy school, he spearheaded its growth from a program with 17 students and one professor (Howell himself) to a professional school with 148 students occupying an entire classroom building, now known as Howell Hall, in his honor.

Howell was active in state and national professional organizations. And he discussed his research on poppies and opium production at several meetings of the American Pharmaceutical Association. The proceedings of the 1908 annual meeting of the American Pharmaceutical Association report:

Mr. Howell, of North Carolina, said he was particularly interested in opium at one time—that most everybody has an ‘opium spell’ at one time or another. He had between five and ten thousand poppy-plants in cultivation last year, and he got opium running 6 per cent, of morphine. The young plants he ate with mayonnaise dressing, ‘and they were all right!’ He described a number of personal experiences, some of them rather amusing, along this line. Most of his efforts came to nothing.

Howell formally shared his research in an article in the June 1925 issue of the Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association. He writes that poppies are well-suited to North Carolina. “To successfully plant and harvest an acre of poppies would be no more tedious, for instance, than to complete an acre of tobacco,” Howell suggests. He records various efforts to produce opium from the plants.

Every possible effort to express, crush, or extract the juice after crushing and thus obtain opium, avoiding the tedious and expensive labor of bleeding the capsules, was tried without success. The addition of ferments and the use of oxidizing agents was fruitless. Nature’s mystic method, retaliation for man’s wounding the plant, was the only way I found of producing opium—scarifying with knives padded to incise very slightly, a white milk juice exudes, which remaining on the capsule hardens and turns brown; this can be scraped off after twenty-four hours. In this time twelve to eighteen alkaloids and an acid or two are developed by the plant.

Howell considers poppy cultivation not just for the production of opium, but also for potential revenue from poppyseed oil.

In the study of the uses and abuses of plants, we see this useful plant—furnishing the best of drying oils, one that has preserved for us, in the realm of art, the wonderful work of master painters—stung, by the inhumanity of man, to the production of morphine. The subsequent introduction of the evils of our opium situation is strictly the work of man. That opium can be produced in North Carolina is certain; that also the seed will mature after incising the capsules has been demonstrated. Just what is the effect on the oil content of the seed, after bleeding, I haven’t had time to ascertain.

Howell proceeds to describe planting methods that will yield the highest number of poppy seeds. European seed, he writes, sells for 10 cents per pound. At such a price, Howell suggests, Tar Heel farmers could earn from $45 to $175 per acre.

Howell concludes his paper by restating papiver somniferum‘s potential value to North Carolina both for the production of opium and for poppyseed.

Lest you conclude that it’s worth planting papiver somniferum in your yard or field, you should know that the Opium Poppy Control Act of 1942 makes it a crime to “produce or attempt to produce the opium poppy, or to permit the production of the opium poppy.” Botany writer Michael Pollan conducted his own experiment and offers words of warning. And for those who’ve noticed poppies growing in highway medians across the state, as the N.C. Department of Transportation is careful to point out, those poppies are a different species and don’t produce opium.