Death noted: Karl Fleming, 84, one of the greats of civil rights reporting.

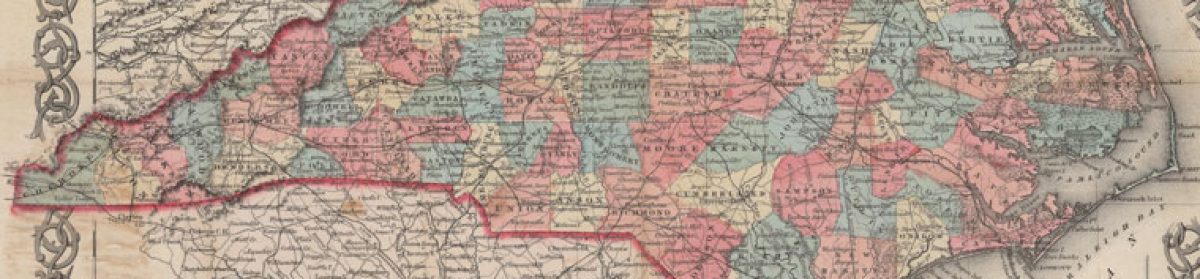

Fleming was born in Newport News, Va., but grew up in the Methodist Orphanage in Raleigh, attended Appalachian State and worked on dailies in Wilson, Durham and Asheville before landing his career-defining job at Newsweek.

This is from his “Son of the Rough South: An Uncivil Memoir” (2006):

“To be an alien reporter in the remote towns of Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana where the young black ‘outside agitators’ were causing trouble was to be almost totally isolated behind enemy lines, linked to the outside world only by a long distance line that I always assumed was tapped. My nerves were constantly on edge. I drank a lot of Maalox and a lot more bourbon. That I had grown up in segregated North Carolina and had a redneck crewcut and deep Southern accent made it even worse. Not only was I a troublemaker, I was a traitor as well… perceived as betraying ‘our Southern way of life’….”

However perilous Fleming’s years on the Southern “race beat” — and he exaggerates not an iota — it was not until, as chief of Newsweek’s Los Angeles bureau, that his life began collapsing amidst a confluence of depression, drugs and alcohol. A beating after a 1965 Black Power rally in Watts left him with a fractured skull, and in 1973 he was scammed out of $30,000 by a phony “D. B. Cooper.”

But in his prime he surely deserved mention alongside his frequent roommate on the road, Claude Sitton.