This Month in North Carolina History

Arguments between states in this country are usually settled more or less decorously and peacefully through debate and compromise. In at least one instance, however, such a quarrel resulted in armed conflict and loss of life. In December 1804, in disputed land along their common border, several Georgians assaulted and killed a Buncombe County, North Carolina constable, and North Carolina responded by sending in a detachment of militia to restore order and assert its authority in the area. Called the Walton War, this incident was part of a series of more peaceful boundary conflicts between North Carolina and its neighbors which were caused by confusion inherited from British colonial rule and territorial pressure resulting from the creation of the new American nation.

At the time of the American Revolution, North Carolina’s boundary with South Carolina was in dispute, particularly in the western part of the state. After the Revolution the new government of the United States pressed states that had claims on land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River to cede those lands to the national government. North Carolina gave up its claim to a broad swath of land from which most of the state of Tennessee was later formed. South Carolina, however, had only a narrow strip to cede between the southern border of North Carolina and the northern border of Georgia. In 1802, after long negotiation with the federal government, Georgia surrendered claim to the territory from which Alabama and Mississippi were formed. As part of the negotiation, the federal government gave Georgia the strip recently ceded by South Carolina, giving Georgia and North Carolina a common border. Unfortunately, this common border had never been accurately surveyed, and there was substantial debate about how it should be defined. The eastern edge of this strip, as Georgia defined it, contained land at the head of the French Broad River that North Carolina believed to be part of Buncombe County which at that time was the only county in the far western end of the state.

This messy situation was aggravated by the presence of settlers in the disputed territory who began coming over the Blue Ridge about 1785. By 1802 there were some 800 people in the area. The fundamental problem was that many of the settlers held their land by grant from South Carolina while many others had North Carolina grants. In the confusion over state authority settlers saw the possibility of losing their land and hence their livelihood. In 1803, to solidify its claim, Georgia organized the disputed territory into Walton County, named for George Walton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Relations between residents in the new county rapidly deteriorated. Holders of South Carolina land grants supported the new county government and resisted the authority of Buncombe County officials. North Carolina grant holders supported Buncombe and refused to acknowledge the Walton County government.

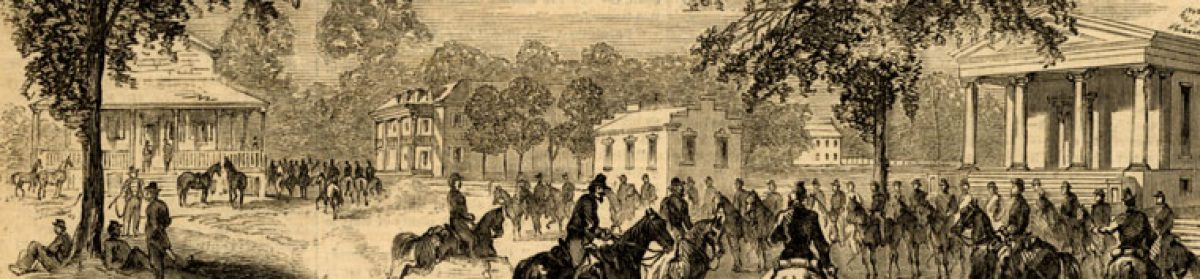

The crisis came in December 1804 when Walton County officials and their supporters attempted to intimidate and possibly dispossess several outspoken partisans of Buncombe. One of these, John Havner, a Buncombe County constable, was struck on the head with the butt of a musket and killed. In response, Buncombe County called out the militia. A detachment of seventy-two men, under Major James Brittain, marched into Walton County on December 19, 1804, where they were joined by twenty-four North Carolinians living in the disputed area. Ten important Walton County officials were taken prisoner and sent to Morganton, North Carolina, to be tried in the death of Havner. The Walton County government was effectively crushed. North Carolina and Georgia continued to quarrel over the disputed territory until 1807 when commissioners from both states met to establish the boundary. Joseph Caldwell, president of the University of North Carolina, and Joseph Meigs, president of the University of Georgia, were charged with making the scientific observations for the party and after several trials established that the true boundary was a number of miles south of its assumed position. The commissioners from Georgia admitted that all of Walton County was in fact in North Carolina.

In the end North Carolina recognized the South Carolina land grants and extended amnesty to those who had opposed the state in the Walton War — except for the ten men accused of the death of John Havner. They, however, had escaped from the jail in Morganton and fled the state, never to be seen again. Although Havner was the only fatality, stories of the Walton War grew over the years creating a legend of the conflict in which truth and fiction freely mixed. In the legend, dozens of Georgians died in pitched battles with North Carolina militia. The frustrated farmers of Walton County, worried about the legality of their land grants, became, in some stories, bands of vicious desperados inhabiting a “no man’s land” beyond the law.

By the late twentieth century the Walton War was almost, but not quite, forgotten. In 1971 Georgia questioned the location of its boundary with North Carolina, and the North Carolina General Assembly, reported by the press to be in a “jocular mood,” passed a resolution urging that the National Guard be called out to defend the border.

Sources

Carpenter, Cal. The Walton War and tales of the Great Smoky Mountains. Lakemont, GA: Copple House Books, 1979.

Reidinger, Martin. “The Walton War and the Georgia-North Carolina Boundary Dispute.” Typescript in North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1981.

Skaggs, Marvin Lucian. “North Carolina Boundary Disputes Involving Her Southern Line.” James Sprunt Studies in History and Political Science, Vol. 25, No. 1. University of North Carolina Press, 1941.

Durham Morning Herald, 12 September 1971 as found in North Carolina Collection Clipping File through 1975, Subject Clippings, vol. 177.