This Month in North Carolina History

On the 4th of July, 1937, a new form of American drama was born on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, as a part of the celebration of the 350th anniversary of the arrival of the first English settlers in North America. The Roanoke Island Historical Association, led by W. O. Saunders, editor of the Elizabeth City Independent, and D. B Fearing, a state Senator from Dare County, approached Pulitizer Prize-winning North Carolina author Paul Green about writing a play on the Roanoke settlement of 1587.

Saunders, on a recent trip to Germany, had seen the outdoor religious plays at Oberammergau in Bavaria and wanted something similar for North Carolina. Green, as a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, had been encouraged by his mentor, Professor Frederick Koch, to draw literary inspiration from local history and folklore.

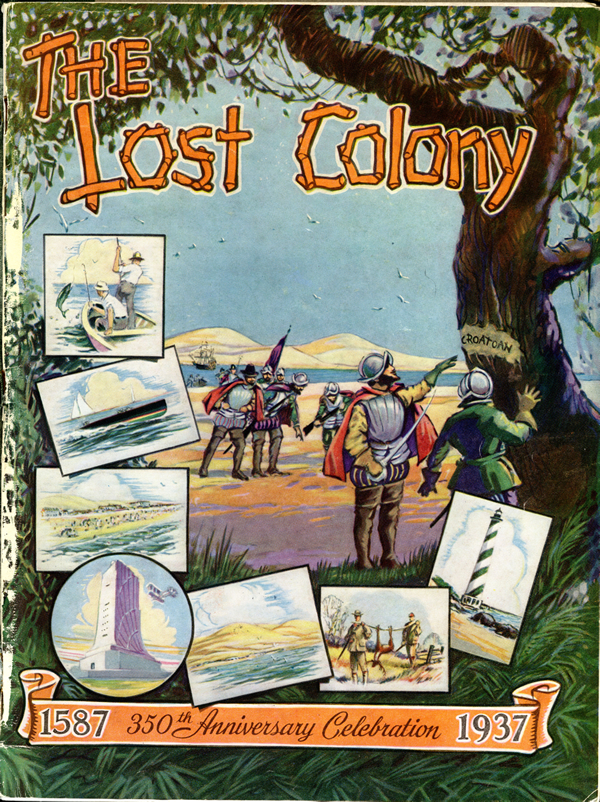

In fact, some years earlier, Green had written a one-act play based on the Roanoke Island experience. Although he considered the play a failure, Green had been inspired by a visit to the island at the time and readily took on the job of writing the new play. Green envisioned a production that would combine drama, music, dance, and pageantry all in a sweeping outdoor setting. He called his creation The Lost Colony: A Symphonic Drama of American History.

Conceived in the depth of the Depression, when supporting funds were hard to find, The Lost Colony was made possible ultimately as a cooperative effort by local people and several state and federal agencies.

Workers from the Roanoke Island camp of the Civilian Conservation Corps build the open-air Waterside Theatre where the play was performed and later several of them joined the cast. The Rockefeller Foundation gave an organ to provide musical accompaniment. The Playmakers of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill provided lighting and other technical assistance and also supplied the director, Samuel Selden. Actors came from the Federal Theatre Project and from among the islanders themselves. The project had the support of North Carolina’s U. S. Senator, Josiah William Bailey and Congressman Lindsay Warren. The U. S. Postal Service issued a stamp to publicize the event and the Treasury minted a commemorative half-dollar which the Roanoke Island Historical Society was allowed to sell for $1.50 to raise money.

The drama and the setting were ready. The question remained, would anybody come? Getting to Roanoke Island on North Carolina’s Outer Banks in 1937 was a challenge. From the North it involved a ferry ride, several miles on a “floating road” over a swamp, and the rest of the way on packed sand roads.

The “easier” route from the west consisted of miles of graded dirt roads and two ferry trips. Nevertheless, approximately 2,500 people attended the first performance of The Lost Colony, and by the end of the summer attendance stood at about 50,000, including President Franklin Roosevelt.

Originally, the play was scheduled to run only for the Summer of 1937. It had been so popular, however, and such a boon to the local economy that it returned in 1938 and by the end of the next year it was being seen by 100,000 people a season. Except for four years during World War II, The Lost Colony has played every summer, becoming an institution on the North Carolina coast and in the American theater. It is one of the mainstays of the island’s economy and has been a training ground for young actors and theater technicians around the country.

Alumni of The Lost Colony include Andy Griffith, Chris Elliot, Eileen Fulton, Carl Kasell, William Ivey Long, and Joe Layton. The Lost Colony also set the pattern for dozens of similar productions, usually referred to as outdoor dramas, staged from Florida to Alaska.

Sources

“The Lost Colony” [editorial], The Carolina Play-Book, vol. XII:2 (June, 1939).

Anthony F. Merrill, “Miracle at Manteo,” The Carolina Play-Book, vol. XII:2 (June, 1939).

Green, Paul, The Lost Colony: A Symphonic Drama of American History ; edited with an introduction and a note on the text by Laurence G. Avery, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Federal Theatre Scrapbook, vol. 1, 1935-1937, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. FC812 G79L

“The Lost Colony,” official website, http://www.thelostcolony.org.

Image Sources

“The Lost Colony” souvenir program, 1937, cover. North Carolina Collection call number Cp970.1 R62L 1937

“The Lost Colony” souvenir program, 1952, cover. North Carolina Collection call number Cp970.1 R62L 1952