Today’s News & Observer has a story about the tragic explosion at the Carolina Coal Company mine in Coal Glen, N.C. on May 27, 1925. There is more information about the explosion, and about the history of coal mining at the site, on the North Carolina Collection’s “This Month in North Carolina History” page.

Library Regulations

We recently came across this list of library regulations from the Charlotte Social Library, published around 1820. We’re still wondering how they enforced the “wet finger” rule.

The Durham Rose Bowl

Fans of the football teams at the major North Carolina universities may be scratching their heads in search of a connection between this state and tonight’s Rose Bowl game. Indeed, it’s been a while since a team from the Tar Heel state traveled to Pasadena: the last was Duke, who lost 7-3 to USC in the 1939 Rose Bowl. But the Blue Devils are able to claim an even more significant connection to the game. Duke had already accepted an invitation to face Oregon State in the 1942 Rose Bowl when the attacks on Pearl Harbor shook the nation. Determined to go ahead with the game, but wary of holding it on the west coast, the game’s organizers decided to relocate to Durham. The Durham Rose Bowl was held on January 1, 1942. Despite the home field advantage, Duke lost to the visiting Beavers by a score of 20-16.

The Duke University Archives has the story of the Durham Rose Bowl, with game photographs, on its website.

Dorothea Dix Hospital and Bird’s Eye Views

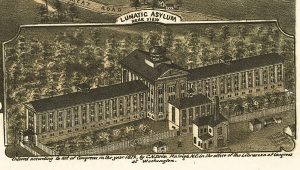

The January 2006 This Month in North Carolina History feature looks at the work of Dorothea Dix in North Carolina and her role in establishing a facility for caring for mentally ill North Carolinians.

The illustration of the hospital shown here is from a “Bird’s Eye View” map of Raleigh from the collections of the Library of Congress. The Library of Congress has digitized a number of these fascinating maps, including ones depicting Asheville, Winston-Salem, Rocky Mount, and Hendersonville.

January 1849: Dorothea Dix Hospital

This Month in North Carolina History

In the 1830s and 1840s the United States was swept by what one historian has described as a ferment of humanitarian reform. Temperance, penal reform, women’s rights, and the antislavery movement, among others, sought to focus public attention on social problems and agitated for improvement. Important among these reform movements was the promotion of a new way of thinking about and treating mental illness. Traditionally, the mentally ill who could not be kept with their families became the responsibility of local government, and were often kept in common jails or poorhouses where they received no special care or medical treatment. Reformers sought to create places of refuge for the insane where they could be cared for and treated. By the late 1840s, all but two of the original thirteen states had created hospitals for the mentally ill, or had made provision to care for them in existing state hospitals. Only North Carolina and Delaware had done nothing.

Interest in the treatment of mental illness had been expressed in North Carolina in 1825 and 1838 but with no results. Several governors suggested care of the mentally ill to the General Assembly as a legislative priority, but no bill was passed. Then in the autumn of 1848 the champion of the cause of treatment of the mentally ill made North Carolina the focus of her efforts. Dorothea Lynde Dix was a New Englander born in 1802. Shocked by what she saw of the treatment of mentally ill women in Boston in 1841 she became a determined campaigner for reform and was instrumental in improving care for the mentally ill in state after state.

In North Carolina Dix followed her established pattern of gathering information about local conditions which she then incorporated into a “memorial” for the General Assembly. Warned that the Assembly, almost equally divided between Democrats and Whigs, would shy from any legislation which involved spending substantial amounts of money, Dix nevertheless won the support of several important Democrats led by Representative John W. Ellis who presented her memorial to the Assembly and maneuvered it through a select committee to the floor of the House of Commons. There, however, in spite of appeals to state pride and humanitarian feeling, the bill failed. Dix had been staying in the Mansion House Hotel in Raleigh during the legislative debate. There she went to the aid of a fellow guest, Mrs. James Dobbins, and nursed her through her final illness. Mrs. Dobbins’s husband was a leading Democrat in the House of Commons, and her dying request of him was to support Dix’s bill. James Dobbins returned to the House and made an impassioned speech calling for the reconsideration of the bill. The legislation passed the reconsideration vote and on the 29th day of January, 1849, passed its third and final reading and became law.

For the next seven years construction of the new hospital advanced slowly on a hill overlooking Raleigh, and it was not until 1856 that the facility was ready to admit its first patients. Dorothea Dix refused to allow the hospital to be named after herself, although she did permit the site on which it was built to be called Dix Hill in honor of her father. One hundred years after the first patient was admitted, the General Assembly voted to change the name of Dix Hill Asylum to Dorothea Dix Hospital.

Sources:

Margaret Callendar McCulloch, “Founding the North Carolina Asylum for the Insane,” North Carolina Historical Review, vol.13:3 (July, 1936).

Dorothea Lynde Dix, Memorial soliciting a state hospital for the protection and cure of the insane: submitted to the General Assembly of North Carolina, November, 1848. Raleigh, N.C.: Seaton Gales, printer for the State, 1848.

Dorothy Clarke Wilson, Stranger and traveler: the story of Dorothea Dix, American reformer. Boston: Little Brown, 1975.

Richard A. Faust, The story of Dorothea Dix Hospital. Raleigh, N.C., 1977.

Image Source:

“Lunatic Asylum. Rear View.” Inset illustration in “Bird’s eye view of the city of Raleigh, North Carolina 1872. Drawn and published by C. Drie.” Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Big Drop

What do acorns, possums, and pickles have in common? Are they: 1) Ingredients in authentic North Carolina brunswick stew; 2) mascots of local high school football teams; or 3) items dropped by North Carolina towns on New Year’s eve?

Residents of Raleigh (acorn), Brasstown (possum), and Mt. Olive (pickle) would have had an easy time with this one. All three communities will ring in the New Year tonight by dropping an item representative of their local history and culture.

One Book, One State

Community reading activities seem to be popular nationwide, but we’re not aware of any “One Book, One State” programs. North Carolina might be coming close with Timothy Tyson’s Blood Done Sign My Name. Wake County has just selected the book for its 2006 “Wake Reads Together,” following close behind Rocky Mount’s pick of the same book for its “One Book, One Community” program. New Hanover County chose Blood Done Sign My Name for a similar program earlier this year, and the current crop of freshman at UNC-Chapel Hill read it over the summer.

Tyson’s compelling history of a racially-motivated murder in Oxford, N.C. in 1970 is interwoven with an honest autobiographical account. Blood Done Sign My Name is a great starting point for a community-wide discussion about race and how we remember the past. If North Carolina were to give “One Book, One State” a try, this book would be an excellent choice.

The Slaves’ New Year’s Day

Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is a moving narrative of her childhood and early adulthood living as a slave in Edenton, N.C. In the chapter “The Slaves’ New Year’s Day,” Jacobs reminds her readers that New Year’s Day was among the most dreaded days of the year for African Americans in the antebellum South. On January 1, slaves were commonly hired out for the year, a process that often split families apart. Jacobs writes

O, you happy free women, contrast your New Year’s day with that of the poor bond-woman! With you it is a pleasant season, and the light of the day is blessed. Friendly wishes meet you every where, and gifts are showered upon you. Even hearts that have been estranged from you soften at this season, and lips that have been silent echo back, “I wish you a happy New Year.” Children bring their little offerings, and raise their rosy lips for a caress. They are your own, and no hand but that of death can take them from you.

But to the slave mother New Year’s day comes laden with peculiar sorrows. She sits on her cold cabin floor, watching the children who may all be torn from her the next morning; and often does she wish that she and they might die before the day dawns. She may be an ignorant creature, degraded by the system that has brutalized her from childhood; but she has a mother’s instincts, and is capable of feeling a mother’s agonies.

The full text of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is available on Documenting the American South.

Ellen Foster at 15

One of the most memorable characters in North Carolina literature returns with the release today of The Life All Around Me by Ellen Foster, by Kaye Gibbons. Ellen Foster, Gibbons’s 1997 novel, opened with the unforgettable line: “When I was little I would think of ways to kill my Daddy.” The novel received national attention when it was selected for Oprah’s book club.

The Life All Around Me finds Ellen Foster at 15, applying for early admission to Harvard, thriving despite her troubled childhood, and still living in North Carolina.

Library Machinery

In reading through the North Carolina University Magazine from 1890, we found the following interesting announcement in the “Library Notes” column:

Students of the Latin and Greek Seminary have begun a card catalogue of the Classical Department in the Library. It is much to be desired that the first move towards providing what is now an absolute necessity may be followed by some determined effort on the part of the Faculty and Societies. There is, perhaps, no other library of thirty-four thousand volumes in the country without a card catalogue. Such a compilation is indispensible—a regular part of library machinery, as much so as the alcoves, the shelves, Poole’s Index, or Encyclopædia Brittanica.