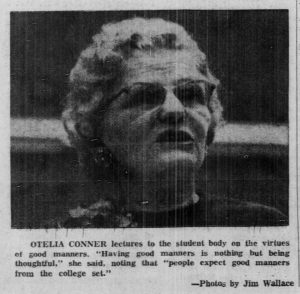

Before there were Pit preachers, there was Mrs. Otelia Connor, an elderly Southern woman who patrolled the manners of Carolina students in the 1960s. Instead of a Bible, she carried an umbrella to thwack those who ran afoul of her rules. Though she reportedly only used the umbrella once, the threat of her wrath was enough to keep many in line—at least in her presence. Connor was known as a campus gadfly, a character whose outsized personality kept her on the pages of The Daily Tar Heel. Her mission and popularity led Time magazine to write a feature in which they coined the term “Oteliaquette” to describe her unique take on campus etiquette. She later appeared on other media outlets, including The Mike Douglas Show and various radio programs. Her moment in the national spotlight faded, though she continued to contribute to campus life until her death in 1969.

Otelia Cunningham Connor, a widow from an illustrious North Carolina family, originally came to Chapel Hill for her son’s graduation from law school in 1957. She fell in love with Carolina, and promptly moved to a modest apartment near campus. Though the mother of two grown children, Otelia adopted the entire student body as her children and set about improving their manners from her base in Lenoir Hall. Her rules ranged from common demonstrations of respect—such as holding the door for older people—to specific prohibitions against everything from chewing gum to bumping the back of her chair. In general, she advocated friendly and thoughtful behavior as hallmarks of a proper upbringing and education. She wrote of her calling, “The world expects good manners of a college graduate. When I correct the young people it is because I think too much of them to see them go out into the world without the rudiments of good manners . . . . Most young people appreciate someone taking the trouble to correct their thoughtlessness.” Otelia Connor, “Manners Minder,” DTH (11 April 1962, pg. 2)

Dean of Students Charles Henderson described Otelia as an “anthropological treasure . . . a throwback to those lost days when manners counted for something, and when elderly ladies thought it their duty to preserve them.” Students were more divided on her mission and methods. Some students appreciated her contributions, as Stanley Cameron wrote to the DTH, “She is truly a pearl. Carolina would not be the same without her. Only a mature, reserved, detached woman like herself could display such keen insight in the life of this university.” Stanley Cameron, “Wants More Otelia, Wellman,” DTH (15 February 1963, pg. 3). Others were more dubious, “Otelia Connor writes such stinging comments on the social manners of our times that she has been suspected of being the pseudonym of a crotchety editor whose pen has an acute case of acid hemophilia.” Alan K. Whiteleather, “The Pen’s Poison, But Manners Are the Motive: ‘Otelia’—It’s No Pseudonym,” DTH (13 February 1963, pg. 1). Indeed, DTH editors had to reassure incredulous students that Otelia was indeed “real” on multiple occasions.

As the self-appointed guardian of manners, Otelia was often viewed as a prude. The 1963 April Fool’s issue of the DTH (March 31, 1963) featured Otelia as a member of an imaginary “Human Relations Committee” to enforce the administration’s abolishment of sex. Indeed, Otelia argued against pre-marital sex during a Di-Phi debate. Otelia was also positively scandalized by a dance called the Thunderbird, citing its resemblance to “an orgy” and expressed concern that a male student might “shake his backsides right off,” continuing, “please excuse me from this bottom-shaking business. Whatever it is, it is not a dance and shouldn’t be classified as a dance.” Otelia Connor, “From Otelia,” DTH (11 July 1963, pg. 4).

Despite her traditional ideas about sex and dancing, Otelia was more progressive regarding dissent. As she wrote in a rare political letter to the editor, “When this country ever reaches the point where it is afraid of new ideas and afraid to let people express themselves in open and free debate, then democracy will already be dead, and waiting to be buried by the communist world.” Otelia Connor, “More Afraid Of J Birchers,” DTH (11 December 1962, pg. 2). This is not to say that she embraced an activist worldview. Although she claimed to support civil rights for African Americans, she objected to continuing demonstrations by the Civil Rights movement, “I think it would be the part of wisdom to consolidate the many gains they have made recently, and give the extreme segregationists a chance to accommodate themselves to the changes which have come about.” Otelia Connor, “From Otelia On Civil Rights,” DTH (1 August 1963, pg. 5).

By the end of her life, Connor had recanted some of her earlier strictures regarding dancing, male-female relationships, and—in her final letter—long hair on men. In that last article, she decried her earlier belief “that everybody should conform to the status quo, and that there should never be any changes.” After exhorting men with long locks to keep their hair clean, she offered words of wisdom for all generations, “Let us all, students and adults, grow into maturity, and be ready to accept the next period of change around the corner.” Otelia Connor, “Time For Change,” DTH (31 July 1969, pg. 6).