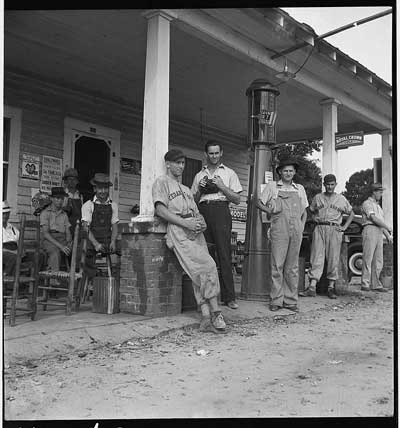

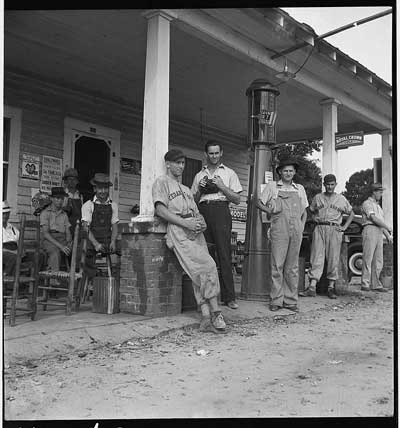

“The [Office of War Information’s] propaganda operation even used and defanged Lange’s [Farm Security Administration] work. In one case, a 1939 photograph of a typical, run-down North Carolina country store/filling station with a group of young men goofing off on the porch was transformed into a World War II poster by cropping and superimposing a message: ‘This is America…. Where a fellow can start on the home team and wind up in the big league… Where there is always room at the top for the fellow who has it on the ball….This is your America!… Keep it free!’

“Lange had made five photographs of the scene, showing about a dozen figures, several in baseball uniforms, preparing to play with a local league; mugging for the camera, they began picking up and swinging one guy by his arms and legs. In the original context, these images signaled the economic backwardness, inactivity and racism of the rural South. At the far end of the porch, distinctly removed from the others, was a black man who did not participate in the roughhousing, but sat tight with a tense smile. In the poster both sides of the image were cropped, and it showed only young white men standing in manly, confident but relaxed postures, ready to play the quintessentially American game.”

— From “Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits” (2009) by Linda Gordon

The official caption on this Fourth of July image puts it “near Chapel Hill,” where Lange worked closely with Howard Odum’s Institute for Research in Social Science. The “Cedar Grove” modestly marking the players’ uniforms is a community in northwest Orange County.

[NCM note: The image above comes from the Library of Congress’s American Memory website: http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/fsa/8b34000/8b34000/8b34021v.jpg]