Just how abusive was Eleanor Roosevelt in her comments on the South? In “Weep No More, My Lady” (Miscellany Sept. 17) W.E. Debnam rendered her as Carry Nation gone radically chic. But the archives of her “My Day” column (http://www.gwu.edu/~erpapers/myday/) reveal a far gentler and more tolerant Mrs. Roosevelt. Three examples from her surprisingly frequent missives from North Carolina:

April 17, 1941: “We visited two housing projects on the outskirts of Charlotte; one for colored people and one for white people in the low income group. They were nice houses and very much appreciated by the tenants. The rents are reasonable and everyone seems very happy.

“The playground for Negroes had very little equipment, but I hope that this is only temporary and that it is going to be possible to give the colored children a similar opportunity for recreation.”

Nov. 19, 1941: “I went to the NYA [National Youth Administration] resident center in Greenville and was tremendously proud of what these North Carolina boys had achieved, for they built all of their own buildings! They have some excellent shops in wood-working, sheet metal work, radio, photography, etc.

“Much of their work is, of course, done for the Army, because NYA training is with a view of making these young men valuable in defense industries as quickly as possible.

“The health program is stressed in North Carolina…. Every boy is given a complete physical examination, and I was appalled to hear that somewhere around 70 percent were found to be undernourished.”

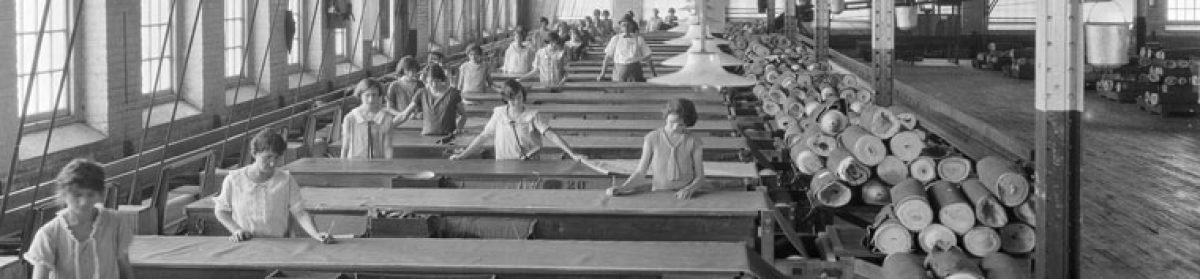

Aug. 15, 1942: “Cannon Mills has evidently been enlightened in dealing with its [16,000] employees. I was told it encouraged ownership of house and land by employees. If work is slack, the building and loan fund does not collect any payments during the layoff period.

“[Charles] Cannon told me most of the work is done on a piecework basis, and outside of a few people in the day laborer class the average earning power of a woman is $22 a week… so I was surprised to find the mill was not unionized.”