At the end of July 2008 thousands of people gathered in Denver, North Carolina, for the annual Rock Springs Camp Meeting. The oldest continuing camp meeting in North Carolina, Rock Springs traces its roots to a meeting held at Rehobeth Methodist Church in Lincoln County in 1794. Camp meetings grew out of the isolation of life in a frontier area and the strong revival spirit of protestant Christianity. Often churches of different denominations would combine to sponsor the meeting, and families would come from miles around to the campground for a series of preaching and singing events which lasted from several days to a couple of weeks. Some families have been returning to the same tents – actually small cabins – at Rock Springs for generations. The accompanying illustration, from our post card collection, shows the permanent “arbor” at Rock Springs. [Thanks to loyal NCM reader Kevin Cherry for this suggestion.]

At the end of July 2008 thousands of people gathered in Denver, North Carolina, for the annual Rock Springs Camp Meeting. The oldest continuing camp meeting in North Carolina, Rock Springs traces its roots to a meeting held at Rehobeth Methodist Church in Lincoln County in 1794. Camp meetings grew out of the isolation of life in a frontier area and the strong revival spirit of protestant Christianity. Often churches of different denominations would combine to sponsor the meeting, and families would come from miles around to the campground for a series of preaching and singing events which lasted from several days to a couple of weeks. Some families have been returning to the same tents – actually small cabins – at Rock Springs for generations. The accompanying illustration, from our post card collection, shows the permanent “arbor” at Rock Springs. [Thanks to loyal NCM reader Kevin Cherry for this suggestion.]

Harry McKown

Horse Racing In The Carolinas

Once again engaged in one of my favorite pastimes — browsing back and forth between the Encyclopedia of North Carolina and the South Carolina Encyclopedia — I was pleased to find that in both of the Carolinas the Sport of Kings was, at least in the antebellum period, the king of sports. A love of fast horses brought us together. From the very beginning of the colonial era, Carolinians talked horses, raced horses, and bet on horses. As early as 1734, horses raced on Charleston Neck for a prize of a saddle and bridle. In our collection there is a copy of a map of Hillsborough, North Carolina, drawn in 1768, which shows a racetrack in addition to the handful of houses and public buildings. Horse racing went into a decline after the Civil War, but has made something of a comeback in recent times in both Carolinas.

The Viewpoints of Jesse Helms

The recent death of Jesse Helms, formerly United States Senator from North Carolina, started me thinking about our collection of transcripts of Helms’s Viewpoint television editorials. Between 1960 and 1972 Helms was the on-air editorialist for the evening news on Raleigh’s WRAL-TV. Our former curator, Bill Powell, talked the television station into letting us have transcripts of the talks, more than 2500 editorials in all. Direct copies of the videos had long since disappeared. Almost from the day we made them available the editorials have been among our most frequently used items, reflecting in part Jesse Helms’s rise to a position of power and leadership in the Senate and in the conservative political movement in the United States. Opinion on the content of the editorials varies widely, if not wildly, but they are never dull. Helms, who had been a reporter or editor most of his life, was a gifted writer and polemicist. Another attraction of the WRAL editorials is that, as a recent biographer has noted, Helms was remarkably consistent in his political views over his long political career, and the opinions of Helms the editorialist link closely to the opinions of Helms the political leader.

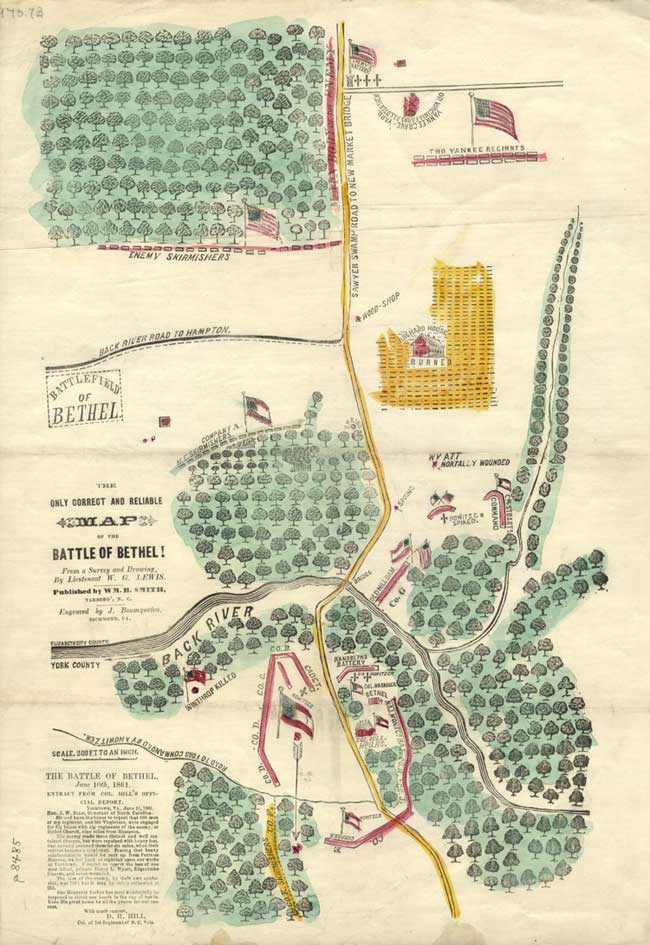

June 1861: Battle of Bethel

This Month in North Carolina History

One could say that the Civil War began for North Carolina on the 10th of June, 1861, near Bethel Church, Virginia. On that day the First Regiment of North Carolina Infantry (6 Months, 1861) engaged U. S. troops in what has been called the first battle of the Civil War.

The First North Carolina Infantry was mustered into state service in Raleigh on May 13, 1861 and was led by Colonel Daniel Harvey Hill of Mecklenburg County. Consisting of colorfully named units from several counties, such as the Hornet Nest Rifles, Charlotte Grays, Orange Light Infantry, Buncombe Rifles, Lafayette Light Infantry, Burke Rifles, Fayetteville Independent Light Infantry, Enfield Blues, and Southern Stars, the regiment reflected the general enthusiasm of the early days of the war.

Then, on May 17, the regiment was accepted into Confederate Service and ordered to Richmond, Virginia. From there it was sent to Yorktown, and went into camp. On June 6 the regiment marched south eleven miles to Bethel Church, Virginia, sometimes called Big Bethel, and bivouacked without tents in the rain. The regiment had brought only 25 spades, 6 axes and 3 picks, but Colonel Hill was determined to put his command in a good defensive position. Dirt flew, and by June 8 the fortification of the camp was substantially complete. That night Confederate General John Magruder arrived at Bethel to take command.

Some nine miles from the First North Carolina at Bethel was the Federal stronghold of Fortress Monroe. Built to protect the United States from foreign attack, the fort served during the Civil War as a staging ground for United States troops and ships and a stepping off point for military operations into Virginia. General Benjamin F. Butler, commander of Union forces at Fortress Monroe, learned of the movement of the North Carolina Regiment and dispatched General Ebenezer W. Peirce with 2,500 troops to attack the Confederates at Bethel.

Discovering the Federal advance, the North Carolinians moved to their prepared positions. Around 9:00 a.m. on the 10th of June the Battle of Bethel began and by 2:00 p.m. it was over. Federal troops made successive uncoordinated attacks on the First North Carolina’s position and, meeting a spirited defense, retired from the field. Federal casualties were 76 while North Carolina’s total was only 11. Of these 11, Henry Lawson Wyatt of Tarboro, North Carolina, was the only Confederate soldier killed.

Over the next four years tens of thousands of North Carolinians served in every theater of the conflict, and North Carolina’s total loss from the war, 40,000, was greater than any other Confederate state. To North Carolina Confederates, however, the state’s participation in the first battle of the war was a source of pride, and “First at Bethel” was a boast for many years in the Tar Heel State.

Sources:

David J. Eicher. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Walter Clark, Ed. Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65. Raleigh, NC: Published by the State, E. M. Uzzell, Printer and Binder, 1901.

Louis H. Manarin, Comp. North Carolina Troops, 1861-1865: A Roster. Vol. III. Raleigh, NC: State Department of Archives and History, 1971.

North Carolina Civil War Sesquicentennial. North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.

Image Source:

W. G. Lewis. The Only Correct and Reliable Map of the Battle of Bethel!: From a Survey and Drawing. Tarboro’, N.C.: Wm. B. Smith, [1861]. North Carolina Collection. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Sound Comes to This Month in North Carolina

This Month in North Carolina for May, 2008, the story of Tom Dooley, is now wired for sound. This is a first for the NCC. The Southern Folklife Collection provided us with an audio file of G. B. Grayson and Henry Whittier performing a version of the Ballad of Tom Dooley from the 1920s. I like it a lot, but it is very different from the “Tom Dooley” made famous by the Kingston Trio in the 1950s. Read, listen, and enjoy!

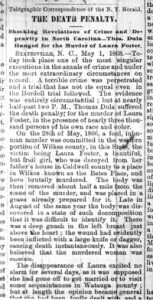

May 1868: The Death of Tom Dooley

This Month in North Carolina History

On the first of May, 1868, Thomas C. Dula met his death by hanging in Statesville, North Carolina, convicted of the murder of Laura Foster in the community of Elkville in Wilkes County on May 25, 1866. Dula’s execution ended a prolonged legal battle that included two trials and two appeals to the state supreme court and began the building of a legend in which fact and fiction mixed to create a story of love, jealously, betrayal, and murder. In the 1950s the Ballad of Tom Dooley, a musical version of the legend, was a hit song for the Kingston Trio.(Dooley was thought to be the local pronunciation of the name Dula.)

Listen to a 1920s version of the ballad by Grayson and Whittier.

Stripped of the melodrama which came to surround them, the more or less agreed upon facts of the case are that on the 25th of May, 1866, twenty two year old Laura Foster left her father’s house on horseback, telling a friend whom she saw on the road that she was riding to meet Tom Dula who was going to marry her. Tom was seen by several people later that day going in the direction Laura had traveled. A day later Laura’s horse returned without her, and she was never seen alive again. Several unsuccessful searches were made for Laura during the summer. Tom was suspected of being involved in her disappearance, and some time late in June he fled the county, eventually going to work on the farm of James W. M. Grayson near Trade, Tennessee. Although no body had been found, a warrant was issued for Tom Dula’s arrest. He was captured in Tennessee by deputy sheriffs from Wilkes County with the aid of James Grayson and was jailed at Wilkesboro on July 11.

Stripped of the melodrama which came to surround them, the more or less agreed upon facts of the case are that on the 25th of May, 1866, twenty two year old Laura Foster left her father’s house on horseback, telling a friend whom she saw on the road that she was riding to meet Tom Dula who was going to marry her. Tom was seen by several people later that day going in the direction Laura had traveled. A day later Laura’s horse returned without her, and she was never seen alive again. Several unsuccessful searches were made for Laura during the summer. Tom was suspected of being involved in her disappearance, and some time late in June he fled the county, eventually going to work on the farm of James W. M. Grayson near Trade, Tennessee. Although no body had been found, a warrant was issued for Tom Dula’s arrest. He was captured in Tennessee by deputy sheriffs from Wilkes County with the aid of James Grayson and was jailed at Wilkesboro on July 11.

Early in August 1866, Ann Melton, a married woman of the Elkville community, told Pauline Foster (no relation to Laura) that she knew the location of Laura Foster’s grave. Under suspicion herself of complicity in Laura’s disappearance, Pauline passed this story on to the authorities, who located the shallow grave containing Laura’s corpse early in September. Tom Dula and Ann Melton were indicted for the murder of Laura Foster on October 1, 1866.

The subsequent trial revealed a web of sexual relationships and violence that both disgusted and fascinated observers at the time. Tom Dula was known as a womanizer, having formed a sexual liaison with Ann Melton—perhaps with her husband’s knowledge—in about his fifteenth year, which lasted until he enlisted in the 42nd North Carolina Regiment of infantry in 1862. Tom returned from the war in June 1865 and took up again with Ann, while at the same time beginning sexual affairs with Pauline Foster, who worked for the Meltons, Laura Foster, and at least one other woman. Some time in March, 1866, Tom became aware that he had a venereal disease, probably syphilis, which had also infected Ann Melton, her husband, and Pauline Foster. Although Pauline seems to have been the source of the infection, Tom believed he had caught it from Laura Foster and threatened her publicly.

Tom Dula was represented at his trial by Zebulon Baird Vance, former governor of North Carolina and future United States senator, one of the best lawyers in the state. Vance obtained a change of venue for the trial to Statesville in Iredell County and got Tom’s trial separated from Ann Melton’s. The state called several witnesses, but relied primarily on circumstantial evidence linking Tom to the vicinity of Laura’s grave and the testimony of Pauline Foster. The jury brought in a guilty verdict on October 21, 1866, but Vance appealed to the Supreme Court of North Carolina, which ordered a new trial. After some delay, the second trial began on January 20, 1868, and once again Tom was convicted. This time the North Carolina Supreme Court upheld the conviction, and Tom Dula was hanged. Just before his death Tom wrote a short note saying that Ann Melton had had no part in Laura Foster’s death. Primarily on the strength of this note, Ann was acquitted.

Over the years story tellers and writers transformed the murder into a tragic love triangle about an innocent young girl, Laura Foster; a wicked, jealous woman, Ann Melton; and caught between them, Tom Dula, a victim of circumstances. Some characters in these stories are changed beyond recognition. James W. M. Grayson, on whose farm Tom worked after he fled Wilkes County, and who aided in his arrest, becomes Tom’s nemesis. In some accounts he is the vengeful sheriff of Wilkes, chasing Tom into Tennessee. In some, he is Tom’s rival for the affection of Laura Foster, bitter with jealousy. The story was also remembered in song, according to legend first sung by Dula himself. Folklorist Frank Warner heard Frank Proffitt of Watauga County, North Carolina, sing a version of the Ballad of Tom Dooley which came ultimately from his grandmother, who knew both Tom Dula and Laura Foster. It was this version that the Kingston Trio recorded in 1958.

Sources

John Foster West. The Ballad of Tom Dula: The Documented Story Behind the Murder of Laura Foster and the Trials and Execution of Tom Dula. Boone, NC: Parkway Publishers, Inc., 2002.

Rufus L. Gardner. Tom Dooley: The Eternal Triangle. Mount Airy, NC: The Author, c1960.

Image Source:

Wilmington Journal, May 8, 1868. North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Audio Source:

“Tom Dooley.” Going Down Lee Highway: 1927-1929 recordings. Davis Unlimited Records, 1977. Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

April 1854: The Fayetteville and Western Plank Road

This Month in North Carolina History

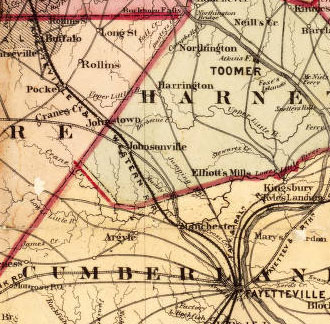

At their annual meeting in April 1854, the stockholders of the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road Company celebrated the completion of their wooden highway. The longest plank road ever built in North Carolina, the Fayetteville and Western stretched 129 miles from the Market House in Fayetteville to the village of Bethania near Salem in Forsyth County. The Fayetteville and Western and a number of other plank roads chartered in North Carolina in the 1850s, were built in response to the miserable condition of overland transportation in the state during the first half of the nineteenth century. Public roads in general were little changed from colonial days. Rutted and rough in good weather, rain turned them into nearly impassable stretches of mud and gloom. Published travel accounts from the period complained bitterly about North Carolina’s horrible roads and blamed them for the state’s economic and social backwardness.

At their annual meeting in April 1854, the stockholders of the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road Company celebrated the completion of their wooden highway. The longest plank road ever built in North Carolina, the Fayetteville and Western stretched 129 miles from the Market House in Fayetteville to the village of Bethania near Salem in Forsyth County. The Fayetteville and Western and a number of other plank roads chartered in North Carolina in the 1850s, were built in response to the miserable condition of overland transportation in the state during the first half of the nineteenth century. Public roads in general were little changed from colonial days. Rutted and rough in good weather, rain turned them into nearly impassable stretches of mud and gloom. Published travel accounts from the period complained bitterly about North Carolina’s horrible roads and blamed them for the state’s economic and social backwardness.

Plank roads, essentially, were highways paved with wood. They appeared to offer several advantages over both stone-paved roads and railroads. They were much less expensive to build and maintain than railroads or roads paved with stone. They could reach small towns and rural areas where rail service was impractical, and they were comparatively quick to build. The state encouraged the building of the Fayetteville and Western by agreeing to invest $120,000 in the company (3/5ths of its stock) if private investors could raise the remaining $80,000. This was quickly done and in October 1849 construction began.

In building the plank road, the Fayetteville and Western first graded, crowned, and compacted the roadbed. Crews dug drainage ditches on either side. Four lines of sills, five by eight inches, were embedded in the prepared road. Eight foot long planks, four inches thick and eight inches wide were laid across the sills and covered with sand. This formed an eight foot wide wooden track which took up roughly half of the road bed. The other half was left so that wagons would have a place to turn off the wooden track when passing. Loaded wagons remained on the wooden surface while empty wagons or carriages moved to the unpaved section. The company built toll houses and gates every eleven miles. Construction costs for the first 88 miles of the road were about $1470 per mile and were in line with costs for building other plank roads.

Revenue for the Fayetteville and Western came from a graduated schedule of tolls. A horse and rider paid one half cent per mile, and wagons paid tolls from one cent to four cents per mile, depending on the number of horses pulling them. Realizing the importance of accurate and honest toll collection, the company made an effort to find reliable toll keepers and paid them $150 a year.

Initial response to the road was enthusiastic, and for the first several years revenues grew. The road was particularly popular with stage coach companies and their passengers. The trip from Fayetteville to Salem, which had previously taken as long as three days, required 18 hours over the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road. The success, however, was more apparent than real. Competition with the railroads, particularly the North Carolina Railroad, was more damaging to the plank road company than its directors had anticipated. Increasingly, users of the road avoided toll stations, bypassing them on older country roads. The most serious problem, however, related to maintenance. The directors of the Fayetteville and Western, based on the experience of plank road companies in Canada and New York State, expected a life span for their road of ten years. Plank roads in North Carolina, however, deteriorated much more quickly, and the road needed replacement after five years. The company had not budgeted for anything like such an expensive maintenance schedule, and by the mid-1850s, revenue was no longer keeping up with expenses. The Civil War, which put a great strain on the road system and disrupted trade and finance, put an end to the struggling Fayetteville and Western, which was abandoned and forgotten.

Sources:

Report of the Board of Internal Improvements of the Legislature of North Carolina: at the session of 1850-51. Raleigh, NC: Thos. J. Lemay, Printer to the State, 1850.

John A. Oates. The Story of Fayetteville and the Upper Cape Fear. Fayetteville, NC: Fayetteville Woman’s Club, 1981.

Robert B. Starling. “The Plank Road Movement in North Carolina,” North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 16: 1 and 2 (January and April, 1939).

Alan D. Watson. Internal Improvements in Antebellum North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 2002.

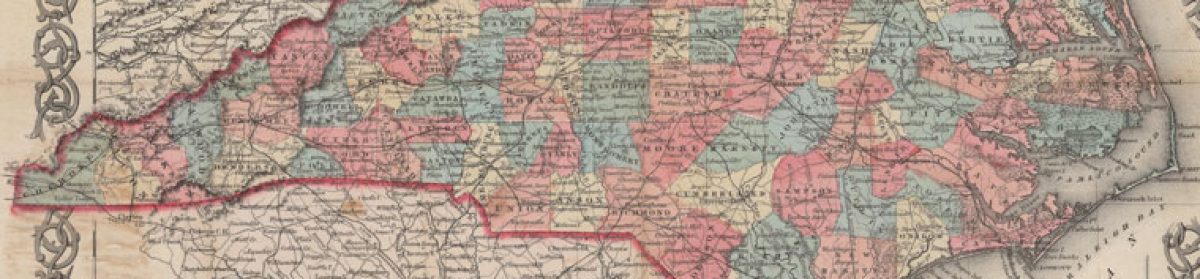

Image Source:

Detail from Pearce’s new map of the state of North Carolina: compiled from actual public and private surveys. Raleigh, NC: Pearce & Williams, 1872. Cm912 1872p.

September 1940: Dedication of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

This Month in North Carolina History

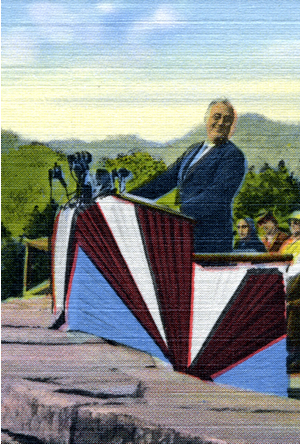

People began arriving as early as seven o’clock in the morning at the parking area at Newfound Gap on the North Carolina-Tennessee border. It was the second of September 1940 and a fine, clear, breezy day at the crest of the Smoky Mountains. By mid-morning there was no space left for parking, and cars were being shunted off onto nearby secondary roads, while their passengers were delivered to the gap in school buses. At five in the afternoon more than 10,000 people had gathered to greet the motorcade from Knoxville bringing President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the mountain top for the dedication of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

People began arriving as early as seven o’clock in the morning at the parking area at Newfound Gap on the North Carolina-Tennessee border. It was the second of September 1940 and a fine, clear, breezy day at the crest of the Smoky Mountains. By mid-morning there was no space left for parking, and cars were being shunted off onto nearby secondary roads, while their passengers were delivered to the gap in school buses. At five in the afternoon more than 10,000 people had gathered to greet the motorcade from Knoxville bringing President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the mountain top for the dedication of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

President Roosevelt had long been a friend of the park, but pressing national and international concerns influenced his speech. Taking as his theme the spirit of the pioneers who had settled the mountains, he called on Americans to show that same spirit in the face of threats from Europe and Asia and sought to rally support for his plans to strengthen national defense. Newspapers reported that he received an enthusiastic response from the crowd and was strongly supported by Governor Clyde Hoey of North Carolina who spoke briefly, as did Governor Prentice Cooper of Tennessee and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. Roosevelt did not neglect the park altogether, however. He spoke of the many varieties of plant and animal life that would be preserved for the future : “… trees here that stood before our forefathers ever came to this continent…” and “brooks that still run as clear as on the day the first pioneer cupped his hand and drank from them.” The park, he believed, would show Americans their past because “the old frontier … lives and will live in these untamed mountains to give the future generations a sense of the land from which their forefathers hewed their homes.”

North Carolinians had been involved in agitating for some sort of national park in the southern Appalachian Mountains since 1899 when the Asheville Board of Trade had been instrumental in organizing the Appalachian National Park Association. For a while interest shifted to the creation of a national forest, and the Weeks Law, passed by Congress in 1911, did authorize creation of forest reserves somewhere in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the southern Appalachians. A shift of emphasis from national forest back to a national park followed the creation of the U. S. Park Service in 1916 and the National Park Association in 1919. The impact of the automobile and the potential of tourism also increased enthusiasm for a park. In 1924 the U. S. Department of the Interior released a report favorable to forming a park in the Smoky Mountains on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee, and in that same year the General Assembly of North Carolina appointed a special commission to promote North Carolina’s effort to secure the park. The commission faced a difficult challenge because the U. S. government would only create the park if the states could provide the land. National parks in the west had been carved out of federal land, but all the land for a park in the Smoky Mountains would have to be bought from private owners. The North Carolina park commission sought to raise money from private gifts and public funds. In 1927 the state of North Carolina provided two million dollars to purchase land, and when this amount plus private gifts would not meet the need, John D. Rockefeller gave another five million dollars from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Fund. In 1930 the governors of North Carolina and Tennessee gave deeds to nearly 159,000 acres in the Smoky Mountains to the United States, and the land was given limited park status. During the 1930s several more purchases rounded out the park, and it received full park designation in 1940.

In the years following its opening the Great Smoky Mountains National Park has proved to be one of the most popular parks in the country. The park is 95% forested of which 25% is old growth, comprising more than 100 species of trees. It is home to 50 species of fish, 39 species of reptiles, 43 species of amphibians, and 66 species of mammals, including its famous black bears. More than 1500 species of flowering plants grow in the park, which was named an International Biosphere Reserve in 1976. It is known for its miles of hiking trails and fishing streams. In Cades Code visitors find historic nineteenth and twentieth century homes, mills and other buildings which illustrate life in the remote areas of the Appalachian mountains.

Sources

Asheville Citizen. September 3, 1940

Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The public papers and addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. 1940 Volume. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1941.

Willard Badgette Gatewood, Jr. “North Carolina’s role in the establishment of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park,” North Carolina Historical Review, vol.37:2, (April, 1960).

July 1885: John Richard (Romulus) Brinkley

This Month in North Carolina History

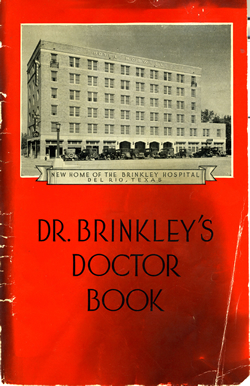

Two torn and fading paperbacks in the vault of the North Carolina Collection describing his medical practice are relics of the life and times of John R. Brinkley who left his birthplace in the hills of North Carolina and, as the famous or infamous “Goat Gland Doctor,” rose from poverty to great wealth and was well on his way back to poverty again when he died in 1942.

Brinkley was born 8 July 1885, the illegitimate son of John Richard Brinkley and Sarah Candace (Sally) Burnett in Beta, Jackson County, North Carolina. His mother gave him the middle name Romulus, but he later changed it to Richard. Brinkley’s father, a so-called “mountain doctor,” had no formal training but had “read” medicine in the office of another physician before setting up on his own.

Brinkley did well in the local schools, demonstrating a quick mind and a prodigious memory. He left school at 16 and became a telegrapher, first for the railroad and then for Western Union. Although his job paid relatively well, Brinkley wanted to become a physician and in 1907 enrolled in Bennett Medical College in Chicago, which he attended for three years. Ultimately he graduated from the Eclectic Medical University of Kansas City in 1915.

Forced to drop out of medical school several times to support his family, Brinkley obtained student medical licenses and often operated on the wild side of medicine. In an episode in Greenville, South Carolina, Brinkley and his partner injected patients with colored water, claiming that it was a miraculous cure for venereal disease. Finally, with his degree from the Eclectic Medical University in hand, Dr. Brinkley set up practice in Milford, Kansas.

It was in Milford that Brinkley hit the mother lode. According to Brinkley, a local farmer, suffering from failing virility asked the doctor to implant in him a portion of the “sex gland” of a male goat. Brinkley obliged and the farmer claimed that his life was transformed. Brinkley publicized the operation and testimonials to its beneficial results widely, and soon patients were lining up for the goat gland transplant.

Brinkley realized the potential of radio to advertise his practice, and in 1923 he began operating station KFKB in Milford, broadcasting all over the midwest. Brinkley did regular programs of medical advice and, through arrangements with pharmacies in the region, began prescribing medicine over the radio.

By the end of the 1920s Brinkley had become famous and wealthy. He had also made enemies. The American Medical Association was investigating him for malpractice. The Kansas City Star had published a series of articles accusing him of fraud, and the newly formed Federal Radio Commission was looking into his broadcasting practices. As a result of all this Brinkley lost his license to practice medicine in Kansas in 1929 and the FRC closed down his radio station in 1930.

During his involuntary retirement from medicine Brinkley turned to politics, and between 1930 and 1934 he ran three times for the governorship of Kansas. In his best showing he polled 30.6 percent of the total vote.

In 1934 Brinkley returned to medicine. He obtained a medical license in Texas and set up a practice and ultimately a hospital in Del Rio on the Rio Grande. Again he was a phenomenal success, making more than twelve million dollars between 1934 and 1938 on his goat gland surgery alone. He also opened a radio station just over the river in Mexico which broadcast all the way to Canada. The doctor enjoyed his wealth, whether relaxing in his mansion in Del Rio or traveling extensively with his family, often in his luxuriously appointed private airplane or on his ocean-going yacht, the Dr. Brinkley III.

Brinkley’s success, however, attracted the attention of his old enemies the American Medical Association and the Federal Communications Commission (successor to the FRC) and brought him a new opponent in the form of the Internal Revenue Service. In 1938 Brinkley lost a splashy libel suit against the AMA which left him branded as a quack. The FCC closed down his Mexican radio station, and Brinkley found himself being investigated by the IRS for non-payment of taxes and by the Post Office for mail fraud. In failing health, Brinkley declared bankruptcy in 1941 and died of cancer in May 1942.

The accompanying illustration, taken from a pamphlet advertising the doctor’s procedures and services, shows the Brinkley hospital in Del Rio. The building is actually the Roswell Hotel. The pamphlet says that the “Brinkley operation is so mild that our patients are guests in the hotel, mixing and mingling with traveling public…”

Sources:

R. Alton Lee. The Bizarre Careers of John R. Brinkley. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002.

Francis W. Schruben. “The Wizard of Milford: Dr. J. R. Brinkley and Brinkleyism.” Kansas History, 14:4 (Winter 1991-1992).

Clement Wood. The Life of a Man: A Biography of John R. Brinkley. Kansas City: Goshorn Publishing, 1934.

John Richard Brinkley. Dr. Brinkley’s Doctor Book. Del Rio, Texas, ca. 1933.

Wild Game Cookout in Sampson County

As we begin to enter the hot days of Summer, like me you may already be yearning for cooler times. Look forward all the way to next January and remind yourself to check on the date for the Annual Wild Game Cookout sponsored by the Friends of Sampson County Waterways. Always a colorful event, the Cookout has in the past featured music and dancers, but the main event, always, is the cooking and eating of some unusual wild game treats. Haven’t had your fill of musk ox? Yearning for some delicious alligator tail? Fancy a nice beaver stroganoff? Sampson County next January is the place for you. Be sure to come early, the stroganoff goes fast.