The Great Depression hit North Carolina hard, effectively lasting from the stock market crash of 1929 to the beginning of World War II in 1941. During the early 1930s, about ¼ of all North Carolinians were on relief programs. Between 1929 and 1933, gross farm income dropped almost 50 percent, and cotton and textile wages declined 25 percent.

The state’s banking industry was devastated. Between June 1927 and June 1932, over 200 banks in North Carolina failed, having lost over $264 million. “[S]till, about the safest place to keep one’s money is in a bank,” the Independent of Elizabeth City reasoned. As 1933 began, the Great Depression showed no signs of stopping.

Runs on banks increased in early 1933, as people in cities like Asheville and Charlotte withdrew their money and left banks with little to no reserves. On February 14, 1933, Michigan became the first state to declare a bank holiday, closing all banks for a week to prevent sudden withdrawals and bank failures. This led panicked customers across the country to pull money from their banks, which, in turn, caused other states to declare bank holidays.

North Carolina was one of the last states to take action. On March 3, legislators passed a law providing the state Commissioner of Banks with authority to declare a bank holiday for state-chartered banks (as opposed to national banks, those that are under the authority of the Comptroller of the Currency). As the Roanoke Rapids Herald reported, lawmakers crafted the legislation despite few banks requesting a bank holiday. The Commissioner was also given authority to limit withdrawals from individual banks.

Using Chronicling America, the Library of Congress’ free, online database of scanned American newspapers, it’s possible to research and learn more about the bank holidays of 1933.

Using Chronicling America, the Library of Congress’ free, online database of scanned American newspapers, it’s possible to research and learn more about the bank holidays of 1933.

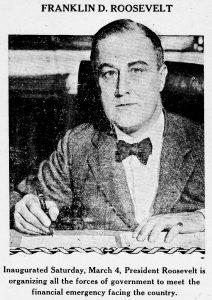

By March 4, 1933, the day that Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, banks nationally held about $4 billion in liquid funds and reserves. Accountholders were seeking to withdraw $43 billion, according to The Independent of Elizabeth City.

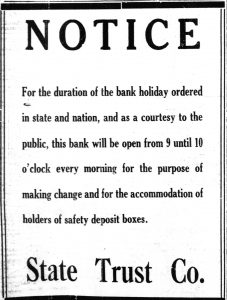

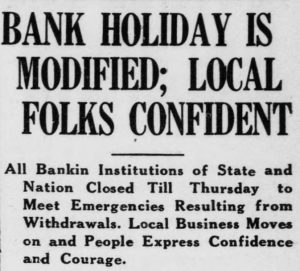

On his 3rd day in office, March 6, FDR declared an immediate, national bank holiday, beginning that day and lasting until March 9, closing every nationally chartered bank across the country. For North Carolina, the order was modified to “resume certain functions as may be necessary to meet community needs”—i.e., for food, salary and wage payments, and other essentials. One state bank announced it would be open for one hour a day to allow customers to access their safe deposit boxes or exchange dollars for smaller denominations or coins.

North Carolinians handled the sudden bank holiday with cautious optimism. A Greensboro judge adjourned superior court because “this is no time to be holding court…” Hendersonville residents were “in good spirit,” accepted the banking holiday calmly, and believed theirs would “be one of the first cities in the state” to return to normal. The Roanoke Rapids Herald reported “more optimism and confidence than in some time” among local businesspeople.

On March 9, Roosevelt extended the national bank holiday indefinitely, while also creating a path for some national banks to reopen, provided they were considered solvent by the comptroller of the currency. On the same day, North Carolina governor J. C. B. Ehringhaus extended the state bank holiday for another week.

Despite the bank holiday extension, North Carolinians were confident their financial institutions would be able to reopen as soon as Thursday the 16th, the end of the bank holiday. Both the Treasury Department and the state banking commissioner noted that if state or national banks were solvent, they could resume operations despite the nationally mandated bank holiday. Hendersonville residents had a “very optimistic attitude…none of the hysteria or uneasiness, prevalent before the banking holiday was declared, will be displayed.”

Despite the bank holiday extension, North Carolinians were confident their financial institutions would be able to reopen as soon as Thursday the 16th, the end of the bank holiday. Both the Treasury Department and the state banking commissioner noted that if state or national banks were solvent, they could resume operations despite the nationally mandated bank holiday. Hendersonville residents had a “very optimistic attitude…none of the hysteria or uneasiness, prevalent before the banking holiday was declared, will be displayed.”

Public confidence in financial institutions seemed to be slowly returning. Two banks in Halifax County reopened on the 16th as expected. The State Trust company received a surprising amount of deposits on that day, according to “particularly well pleased” bank officials.

Public confidence in financial institutions seemed to be slowly returning. Two banks in Halifax County reopened on the 16th as expected. The State Trust company received a surprising amount of deposits on that day, according to “particularly well pleased” bank officials.

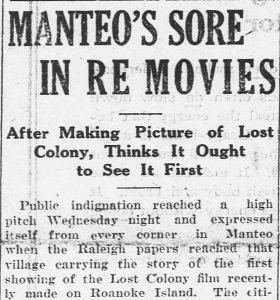

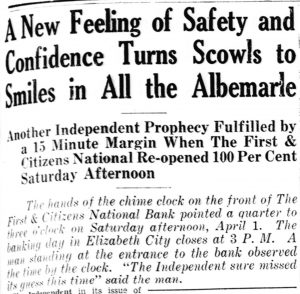

Other banks took longer to reopen. The Bank of Manteo reopened more than a week later. The First & Citizens National Bank of Elizabeth City finally reopened on April 1, after its officers discussed the possibility of conservatorship.

The First National Bank of Salisbury reopened in early June, nearly three months after the bank holiday. That month, FDR signed the 1933 Banking Act, which created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, insuring bank deposits in the case of bank failures. By July of the following year, all but two North Carolina banks had joined the FDIC.

For many residents throughout the state, despite the bank holiday and new financial regulations, the Great Depression continued. In August 1933, the Polk County Bank & Trust Company closed its doors and went into “voluntary liquidation”—one of the first banks to close since the bank holiday. The town of Scotland Neck was completely “without banking facilities” well into September 1933.

The Independent of Elizabeth City named 1933 “one of the darkest and most trying” years in North Carolina history, but because of North Carolinians’ strong resolve and decisive action across all levels of government, people entered 1934 filled with optimism about the years to come.