Like their Scot and sassenach ancestors almost 100 years ago, McCords, McGraws and McClellans will gather in the Port City in the coming week to mark the birthday of Scottish poet Robert Burns and celebrate all things Scots.

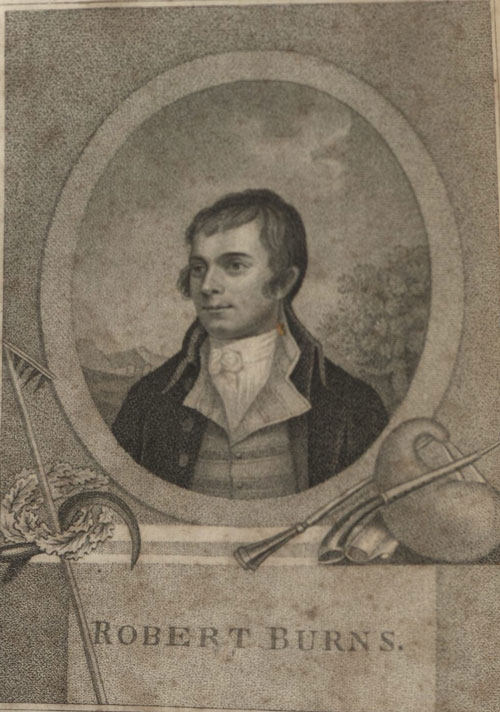

The Ploughman Poet, as Burns was known, was born in the Scottish lowland town of Alloway on January 25, 1759. Although the son of tenant farmers, Burns gained an education and, by all accounts, was an avid reader. He found the pen more enticing than the plough and, at 27, published his first collection of poems. Such works as To a Louse, To a Mouse and The Cotter’s Saturday Night garnered Burns fame and he moved to Edinburgh where he was celebrated in literary and social circles. Burns continued to write poetry while also enjoying plenty of drink and female companionship. He fathered several children out of wedlock.

Burns’s time as solely a poet was brief. He spent much of his earnings from published poetry over an 18-month period and, consequently, he was forced to take a job as a tax officer in the town of Dumfries. Though working, he continued to write poetry as well as songs. He also resumed his relationship with Jean Armour, a women with whom he had twins. Over time, however, Burns’s health declined and he died on July 21, 1796. He was 37. Burns was buried with military and civilian honors.

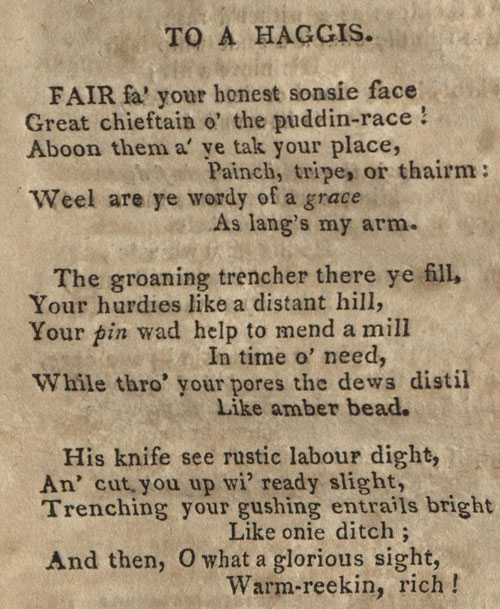

The tradition of Burns Night or the Burns Supper is believed to have started several years after the poet’s death. A group of his friends gathered on July 21 to celebrate his life. Over time fans of Burns’s poetry formed clubs and began holding celebratory meals on the date of his birth. These days the Burns supper often follows a prescribed order with “The Selkirk Grace,” penned by Burns, preceding the parade of the haggis, during which a bagpiper leads someone bearing the haggis to the table. The host of the supper then recites Burns’s “To a Haggis.”

Along with haggis, celebrants dine on neeps (turnips) and tatties (potatoes). Wine or ale accompanies the meal. Whisky (to use the Scottish spelling) has often been used during the cooking of the haggis. After the meal participants listen to the “Immortal Memory,” a recitation of Burns’s biography and a toast to the poet. Then there is a toast to the lassies. More poems and songs may follow before the evening concludes with guests rising to join in singing Burns’s “Auld Lang Syne.”

The Burns supper had made its way to the United States by the mid-19th century. A New York City celebration of the 100th anniversary of Burns’s birth, in 1859. reportedly drew large numbers. It was held at the Astor House hotel and featured an oration by Henry Ward Beecher.

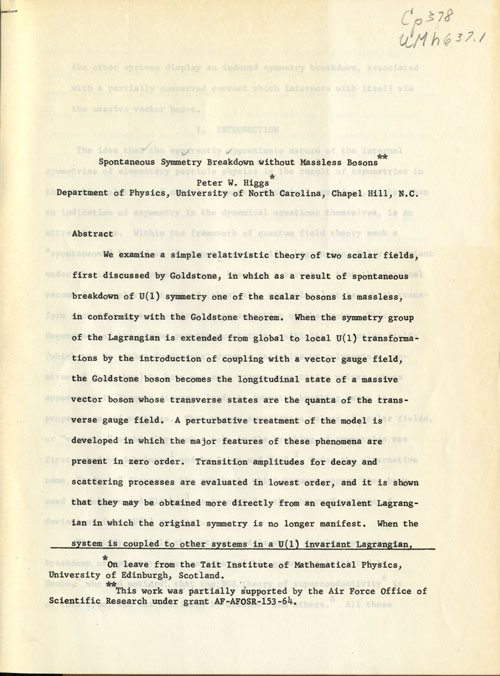

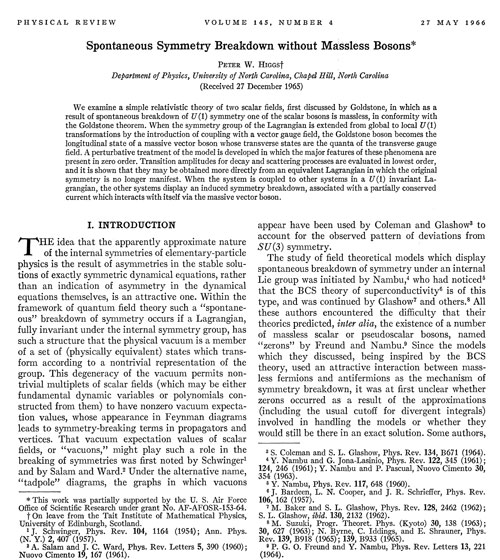

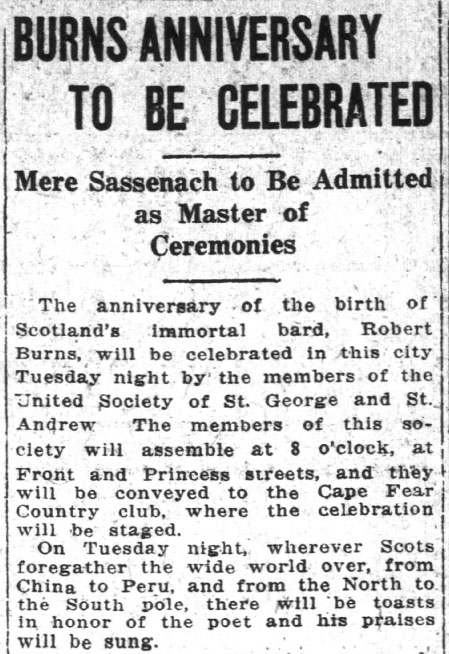

It is unclear when the first Burns supper took place in North Carolina. As Celeste Ray points out in Highland Heritage: Scottish Americans in the American South, celebrations of Burns’s birthday began as a lowland Scots tradition. Consequently they were likely, at least initially, an uncommon occurrence among the Scots-Irish (many originally from the Scottish highlands) who settled in North Carolina in the 18th and early 19th centuries. But, as the clipping from the Wilmington Morning Star suggests, by the early 20th century North Carolinians of Scottish descent had latched on to Burns’s birthday as a way to celebrate their heritage. The state was home to St. Andrews societies and, eventually, Burns societies. Donald F. MacDonald, a one-time Charlotte News reporter who played a crucial role in the founding of the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games, helped form a Robert Burns Society in Charlotte in 1955. In fact the publicity surrounding that group and its Burns supper is said to have played a part in connecting MacDonald with Agnes MacRae Morton, the mother of Hugh Morton and another key figure in the founding of the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games.

These days Burns suppers take a variety of forms on this continent and back in Scotland. Ray writes of a Burns supper she attended at Old Salem that featured homemade haggis in a deer stomach. And the 2014 Big Burns Supper in Dumfries will feature three days of music and performances as well as the release of Hamish the Haggis