I was lucky enough to join the Archival Seedlings program through UNC Libraries’ Community-Driven Archives project with the idea of assisting residents in Bristol, twin cities that span across Tennessee and Virginia, with organizing and making available some of the narratives they wanted to share with their communities and the broader world. Their stories include the history of Blackbottom, the urban-removed Black business district, and the Historic Lee Street Baptist Church that survived relocation.

Through months of conversations and technical support from UNC staff and local elders, we were able to identify project goals and methods for achieving a helpful and sustainable outcome. Unfortunately, the phrase, “the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry,” came true with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and public health crisis. For this project, the rapid spread of the virus meant I could not engage with elders in Bristol who were leading the narrative development because face-to-face conversations would certainly place those leaders in danger.

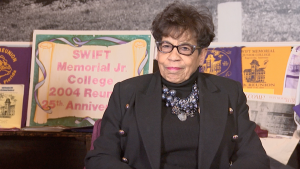

With the assistance of UNC staff through several brainstorming calls, we were able to identify a project closer to home that could be implemented with minimal contact with residents. In 2012 and 2013, I had helped conduct oral history interviews with a number of community members associated with Swift Memorial Institute, a late Historically Black College in Rogersville, Tennessee. Additionally, I had access to more formal interviews with scholars and authors on that subject matter. My project then became curating these raw interviews into something that would be useful to Swift alumni, the community, and researchers interested in their stories.

Swift Memorial Institute

In 1883, Swift College was established by the Presbyterian church as a place of learning for formerly enslaved African Americans and their children. Swift’s sister school, Maryville College, enrolled African American students alongside white students until 1901, when the State of Tennesse passed a law barring private schools from hosting integrated classes. Maryville sent its African American students along with $25,000 of its own endowment to Swift, changing its name to Swift Memorial Institute and fortifying efforts to construct new buildings and expand its curriculum. Swift also served the region’s high school students.

Shortly after Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Swift closed its doors and, in 1955, its administrative building was torn down. The remaining buildings and campus grounds now host the local Hawkins County School System’s offices and maintenance department. Throughout its 72 year history, Swift Memorial Institute has been a beacon for African American communities, offering a standard for African American education and institution building.

One of the feeder schools to the college was Price Public, a primary school located adjacent to the Swift campus. For nearly 20 years, my cousin, Stella Gudger, coordinated the preservation and restoration of this last remaining Black school in the town of Rogersville. Through her efforts and support from the community, the building now operates as Price Public Community Center & Swift Museum. In 2012, I was approached by Cousin Stella to help conduct oral histories with Swift alumni and researchers with information on the early history of the college. That work provided the content for a short documentary on the school and the large amount of stories about Swift associated with my Community-Driven Archives project.

The stories I compiled and made accessible through this Community-Driven Archives project were personally important as a mechanism for repairing some of the invisibility of Black narratives of Hawkins County, Tennessee in dominant local narratives. My own long familial history with the immediate area has propelled my interest in finding creative ways to put these narratives in front of those with roots in the area and to interject this history into the broader historical considerations of the region. By doing this work, I also came to a good understanding of the continued importance of Swift College to those who attended the school—the value the immediate community places on the HBCU’s history and the pride associated with being a “Swiftie.” With the removal of Swift’s main administrative building, elders are relying on their stories and the efforts of the Swift Museum as stewards of this special space and its lessons for future generations.

Project Support through Archival Seedlings

Through the support of UNC Libraries’ Community-Driven Archives program, I was able to convert a collection of older video files from .avi to .mp4, edit them down for content, and upload 28 oral histories and interviews to YouTube. Project contributor Amira Sakalla then worked to transcribe the nearly six hours of interview content, made possible through Archival Seedlings program funding. Coming out of this project, we were able to deliver these videos to the Price Public Community Center & Swift Museum in their preferred format, DVDs, and supply printed transcriptions neatly bound for reading. To ensure redundancy and public availability, we’re also making the interviews and transcripts available to the Hawkins County Archives and the East Tennessee Historical Society in Knoxville. For researchers based outside of the area, all materials are accessible through a dedicated webpage through the Black in Appalachia project, along with other Black history materials associated with Rogersville and Hawkins County.

Throughout this project and the obstacles presented by the global pandemic, I’ve learned the value of being nimble with my big ideas and plans. It has also been a healthy reminder of the importance of moving narratives off of the hard drive and into the streets, so to speak, mindful of the steady passing of elders who contributed to this body of work. In a tiny way, this project is dedicated to the late Dessa Parkey-Blair, a lifelong educator from the hills of Hancock County, Tennessee who said, “All you got to do is sit tight, listen, learn all you can, do all you can, say all you can, but be right. That’s how I do life.”

For more about the Archival Seedlings initiative on the Southern Sources blog:

Archival Seedlings: Resourcing Local Collaborators Across the American South

Community-based, in a Digital Space

The Community-Driven Archives Project at UNC-Chapel Hill is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Follow us on Twitter: @SoHistColl_1930 #CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC

Throughout the harrowing challenges of 2020, our Community-Driven Archives Team has been in conversation with our

Throughout the harrowing challenges of 2020, our Community-Driven Archives Team has been in conversation with our