Our unique approach to archival workflows is one thing that sets community-driven archives approaches apart from mainstream archival methods. Traditionally, archivists stick to access and preservation and leave interpretation and storytelling to the researchers. But what happens when we listen to what our audiences want? We find ways to help them tell meaningful stories about their communities’ history.

Our Core Audiences and Understanding What Matters to Them

Within our community-driven archives (CDA) project, audience means a lot to us. This has been true since the beginning of our grant project, and it is getting clearer as we head towards wrapping it up and sharing what we have learned.

Our project strives to support and amplify historical projects by and for communities underrepresented in institutional archives. Our priority audience is community-based archive projects: groups of people who are interested in creating an archival project documenting their own community. We also work with individual history keepers: people, like family genealogists and community organizers, wanting to document and share histories currently missing from dominant archives and narratives due to legacies of injustice.

While brainstorming for what will go on our new project website (coming soon), our team looked at all the tools and resources that we have created with our project partners since the start of the grant. We asked ourselves, what kinds of resources are most useful to our core audiences?

We noticed that one of the most common resource requests that we receive from our community collaborators is for more tools about storytelling. In response, we have created new resources on topics like “the art of storytelling” and “how to create an exhibition.”

But what do we mean by storytelling and why should archives professionals care?

Making a Case for Storytelling in Community Archives Projects

Archives have historically prioritized the access and preservation of historical records over the interpretation of history, leaving the latter to researchers. For community archives projects, we believe it must be different.

Community archives projects address gaps in the dominant historical record and complicate mainstream historical narratives. Communities want their stories told on their own terms. Through building an archive, the collecting of history supports the (re)telling of it.

In many cases, the stories uncovered through community-based collections are not otherwise known. Due to legacies of racism, settler colonialism, patriarchy, and other forms of oppression, histories by and for Black, Indigenous, people of color, women, and LGBTIQ people have been hidden or silenced. As a result, beyond building their collection, many history keepers also want to broadcast the stories they’ve researched and curated through their archive. Many history keepers want to control how their community’s stories get told, rightfully questioning outside researchers’ and institutions’ motivations.

Our collaborators and partners share their communities’ stories through a variety of methods: exhibitions, public programs, websites, social media and blog posts, documentaries, short videos, and more.

We believe that archival professionals like ourselves working with community archives projects must consider the importance of storytelling. Through community collaboration, we have the opportunity to support both the safeguarding and sharing of stories.

Ideas for Archival Institutions

Since the beginning of our community-driven archives project, our work has extended to train and resource history keepers to share stories they uncover through developing a collection.

Oral histories easily lend themselves to exhibitions and other vehicles for sharing stories with visitors. Members of our team have trained local history keepers to conduct oral histories as a path to preserving memories. From there, we have worked with our community partners to incorporate oral history clips and collections materials into physical and digital exhibitions and short documentary videos that narrate important stories. One of our pilot partners, the Appalachian Student Health Coalition, created a web-based storytelling project that draws on video interviews and data visualizations to share its members’ contributions to rural healthcare in Appalachia.

Through our Archival Seedlings program, we help our ten resident Seedlings develop an archival collection and share their historical project with chosen audiences. For some Seedlings, the websites, videos, blog posts, and exhibits they create to highlight their collection are the only places their audiences can find those histories. While some Seedlings are working with traditional institutions and repositories to preserve and share their finished projects, others are choosing to keep their collections with history keepers in their own communities and to take on project promotion and outreach themselves.

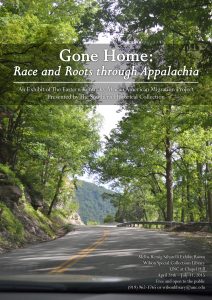

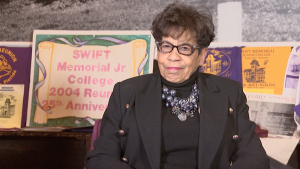

One Seedlings participant, William Isom II, is compiling a collection of video interviews with alumni from the historically Black Swift Memorial Institute in Rogersville, TN into a video that will be on view in the museum located on Swift’s historic campus. In addition, one of our pilot partners, the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project (EKAAMP) has recently launched an exhibition sharing the oral histories and archival materials it collected through community-based research. These are great examples of how a collection can be “put to work” to share stories.

Storytelling Resources

Storytelling resources are available along with other related tools and trainings on our website.

For more about community-based archives on the Southern Sources blog:

What’s in an Archive? Deciding Where Your Historical Materials Will Live

The Community-Driven Archives Project at UNC-Chapel Hill is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Follow us on Twitter @SoHistColl_1930 #CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC