![]()

Bernetiae Reed, CDAT Project Documentarian and Oral Historian, reflects on her participation in the Eastern Kentucky Social Club (EKSC) Reunion and exhibit by Dr. Karida Brown of EKAAMP in St. Louis, Missouri.

Time was a blur as I traveled to St. Louis and back! Plans had been made. I would be taking selected archival items from the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project (EKAAMP) deposit collections on a road trip! I ask you, how best to see and experience America? How best to envision a different time? Nothing like it! So, off I went . . . I will spare you the intricacies of my journey, but highly recommend travelling behind trucks at night to safeguard against hitting a deer!

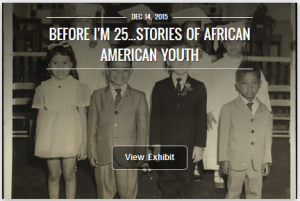

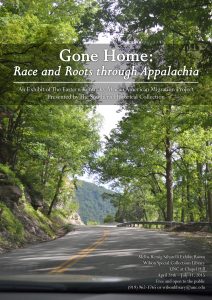

My goals on this journey, as Project Documentarian and Oral Historian for the Community-Driven Archives grant at the SHC, were to record events and assist with the installation of the exhibit. Two related events were taking place stemming from African American mining communities in Eastern Kentucky. The 49th Annual Eastern Kentucky Social Club gathering and the release/book signing for Dr. Karida Brown’s book, Gone Home: Race and Roots through Appalachia which included the launch of a travelling exhibit.

Figure 1: (l-r) Dr. Karida Brown, Hilton Hotel Staff, Richard Brown holding posters (Karida’s father) and Dwayne Baskin pulling program items from hotel storage

As soon as we settled into the downtown St. Louis hotel, Friday (August 31st), morning and into the Saturday afternoon, we were fanatically installing the exhibit. Tracy Murrell, an Atlanta-based artist and curator, was shepherding her vision of this exhibit to life. Tracy had been hired by Karida for the project. Use of wonderful shear wall hangings printed with photographic images transported us to the coal mining town of Lynch, Kentucky. Additionally, a throw-back-in-time couch took you to a typical home from the era.

Figure 2: Tracy Murrell and others work to install the exhibit

Many moments stand out for me. Karida opening the doors to the exhibit, Jacqueline Ratchford reacting to seeing her prom dress on display, Derek Akal talking about his current plans to become a miner, people interacting with artifacts in the collection, and so much more. People reminisced, touched, told stories, laughed, cried, and so much more . . . this was their family and a part of them! Needless to say, I videotaped only a small portion of everything that was happening. From hotel lobby . . . to each event venue . . . to brief walks in downtown St. Louis . . . to church service in the hotel . . . time flew by! Karida beamed as she signed her book. Everywhere people were greeting and hugging old friends. And a beautiful welling of emotions came in watching the young praise dancers who performed during the church service. I was captivated by their pantomime . . . brought to laughter and tears. And had a special sense of wonder for the youngest mime, not understanding how one so young could draw on life’s joys and pains so well. Finally, satisfied that the power to be moved again by this performance and the journey to St. Louis was possible with what had been recorded.

Figure 3: A high school letterman’s sweater and a pink prom dress from the EKAAMP archive set in front of images from Lynch Kentucky.

We included a clip of the praise dancers so you too could experience a piece of performance!

We post every week on different topics but if there is something you’d like to see, let us know either in the comments or email Claire our Community Outreach Coordinator: clairela@live.unc.edu.

Follow us on Twitter @SoHistColl_1930 #AiaB #yourstory #ourhistory #communityarchives #EKAAMP #HBTSA #SHC #SAAACAM #memory #StLouis #CDAT #EKSC #GoneHome