When it comes to protecting intellectual property that is part of your or your community’s history, it helps to understand what legal rights apply to your materials.

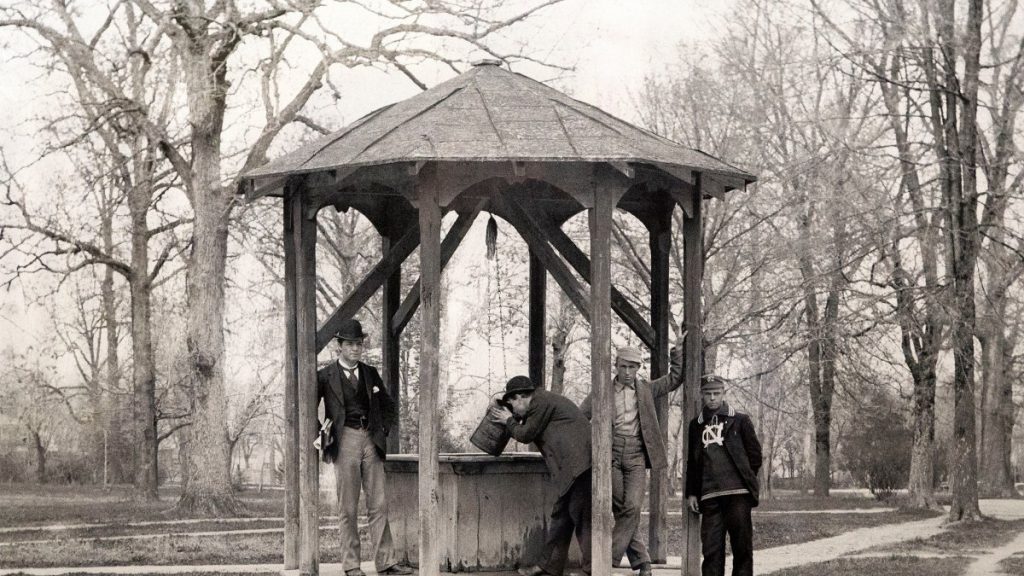

Community-based archives are a pathway for groups of people to exercise self-determination over the collection and interpretation of their histories. Historically marginalized communities draw on community-archival methods to preserve and share stories that are often missing from institutional archives and dominant historical narratives.

It is especially important to many of our partner history keepers through our Community-Driven Archives initiative to know what rights they and their community collaborators have over their stories and historical records. This requires an understanding of copyright and how it works.

What is copyright?

According to Anne Gilliland, Scholarly Communications Officer with UNC Libraries, copyright is your legal right to determine the permitted uses of your tangible expressions of creative work. What does that mean and what kinds of things amount to “tangible expressions of creative work”?

This is not an exhaustive list, but it does give you a sense of what kinds of things are legally under copyright:

-

- Musical compositions

- Films

- Artwork/media

- Oral histories

- Photographs

One big takeaway is that copyright does not cover non-recorded stories and ideas.

Many of our collaborators are rightfully concerned about their control over future uses of their shared stories and materials. Many have heard about or know of an example of someone’s story making its way to Hollywood or on the radio or even featured on a city-sponsored project without the knowledge of that person or their descendants.

While acknowledging on one hand the gaps, omissions, and injustices of U.S. laws, our goal as a Community-Driven Archives Team is to help history keepers get familiar with a few best practices for making use of the legal protections that are available. We also want to help groups and institutions who work with oral histories and other people’s historical materials take the proper steps before making use of someone’s story or creative work.

Copyright Best Practices

Best Practice #1: Assume that every creative work is under copyright until you know that it is not.

Most creative works are automatically under copyright unless the copyright holder (the creator or their designated heirs) explicitly gives away their copyright or the record goes into the public domain, which usually takes about a century.

Just because you found it online does not mean that you are free to share it. Most online materials are under copyright.

Look for ways to seek permission to share or reuse the item in question. Sometimes, a simple web search will clue you in on permission requirements; other times, you may need to take the time to track down heirs and make phone calls to descendants for consent. If you are working with an institutional archive, staff members can help you track down creators for permission. If you cannot find someone to provide consent, then you can investigate fair use, which is a framework to help you assess whether you can fairly justify the use of copyrighted materials without the permission of the creator or someone authorized to provide consent.

The item may also be free to use because it is in the public domain. This applies to many items, including those created by the federal government and those that date back to the early 20th century or earlier. To learn what groups of historical and cultural materials have passed into the public domain, you can check out this chart updated each year by Cornell University.

Best Practice #2: For oral histories, interviewers should always ask their interviewees for their consent and their terms of reuse.

According to our lawyer-in-residence, Anne Gilliland, oral histories are considered a joint creation between the interviewer and the interviewee.

For interviewers:

If you are a community archivist wanting to preserve and/or share oral histories you have collected, you should create a consent form where your interviewee gives you permission to record their story. This form should outline the allowed uses for the recorded interview. Consent forms also ask about additional restrictions, if any, that interviewees require for the sharing of their interview. If it applies, interviewees should also be informed about the institutional repository (i.e. archive, library, museum, etc.) to which their materials will be donated.

A license is a way of communicating the terms for allowed uses of creative works (such uses include: display, distribution, performance, reproduction, derivative works, and audio transmission). For example, a license can state that someone’s interview should be used only for educational and/or nonprofit purposes, or only if the original format is not altered (i.e. no derivative works can be adapted from the interview). Creative Commons licenses are popular and give creators standardized language for their terms of reuse.

For interviewees:

Unless the form you sign says so explicitly, signing a consent form does not mean that you are giving away your copyright. Creators maintain their copyright for at least the duration of their lifetime, unless they formally agree to end their copyright. If you are being interviewed, it is important that you feel comfortable with the terms of the interview. Take the time to read through the consent form to make sure you agree with the license laid out there. Read the section above for more information about creating a license.

Best Practice #3: Be upfront about your mission and goals with your audience and your collaborators.

Why are you making your works or materials available to members of the public? Make it clear to potential audiences. For example, if you want to share your creative works with public audiences for educational purposes, that tells you something about your mission. Perhaps your mission is to inspire people in Chapel Hill, NC to take action for environmental justice through sharing nature photographs from the 1970s and 80s with web users. Write up that mission and share it on your website. If you are concerned that people might use your photographs for purposes outside the scope of your mission, make sure your license for reuse is somewhere prominent and easy to find on your site.

If you are asking someone to sign a consent form that would allow you to share their digitized image, oral history, or creative work with public audiences, be upfront with them about the mission and goals of your project. This helps build trust. If your collaborator likes your project and appreciates your intended use of their materials, they will be less likely to require additional restrictions be placed on the material, which will make it easier for you and others to use and share it over time. Again, it is important to make sure you and your collaborator agree on the terms of use for their materials, and that the related license is easily accessible with the terms of use clearly presented to public audiences.

Best Practice #4: For sensitive materials, consider alternative ways of sharing them with selected audiences.

If you are concerned with how members of the public will share or use your materials, think about limiting your terms of use.

For digitized items (physical papers or photographs that are scanned and made into a digital file), consider creating a private space online to share them only with select members of your community. Or share them widely but upload a version of the file that is stamped with a watermark to prevent unintended uses. Signing a consent form to share your digitized materials with any history keeper or institutional partner does not mean you are giving away your copyright.

If you are sending items to a repository (e.g. institutional archive, library, museum, etc.), make sure you are also clear with that institution on your terms of use. Review all forms they ask you to sign to ensure that you retain your copyright and ask that your preferred license be included (a.k.a. your terms of use). Let the institution know if you intend for your materials to be a loan or a permanent gift. If it is a loan, indicate when and under which conditions materials should be returned to their owner.

If you are worried about any unintended uses of digitized materials shared with a repository, consider asking your institutional partner to keep your materials off the internet or to share them selectively, as outlined above.

Additional Resources

-

- Creative Commons License Chooser tool

- Copyright and Cultural Institutions by Peter Hirtle

- UNC Libraries’ LibGuide on Fair Use

For more about community-based archives and considerations for project partnership on the Southern Sources blog:

What’s In an Archive? Deciding Where Your Historical Materials Will Live

The Community-Driven Archives Project at UNC-Chapel Hill is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Follow us on Twitter: @SoHistColl_1930 #CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC

Sounds great, but why all the hoopla? Backpacks aren’t exactly cutting edge. I think it is the mix of the un-apologetically bright colors of the kits (though we do offer some more muted tones) and the awe that digging into a family or community’s past almost always elicits. But there are other components to the backpacks, not always mentioned in the emails. Social justice, commemoration, and community healing often feel like implicit threads of the conversations and the projects new colleagues talk about.

Sounds great, but why all the hoopla? Backpacks aren’t exactly cutting edge. I think it is the mix of the un-apologetically bright colors of the kits (though we do offer some more muted tones) and the awe that digging into a family or community’s past almost always elicits. But there are other components to the backpacks, not always mentioned in the emails. Social justice, commemoration, and community healing often feel like implicit threads of the conversations and the projects new colleagues talk about.