Category: Archival Work

Our year of focus on “radical empathy”: a summary

Background

In the 2021-2022 academic year, the staff of the Southern Historical Collection employed three graduate students working on projects that engaged elements of radical empathy. Flannery Fitch and Michelle Witt were working on On These Grounds (a project focused on the lives of enslaved individuals connected to the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill), while Brianna McGruder was involved in the Hungry River Collective (a project focused on the historic lives of incarcerated women in Cherry Hospital Goldsboro, NC). As the supervisor of all three students, SHC Curator, Chaitra Powell, initiated a bi-monthly discussion group that encouraged the graduate students to explore readings, their own experiences, and their projects to help develop a working definition of what radical empathy means to us. This blog post includes our reading list, a summary of our discussions, and offers a few personal reflections/connections.

Our 6 tenets of Radical Empathy

1

Radical Empathy requires an analysis of where power and/or money reside. We thought about this in relation to work happening to tell stories about Dorothea Dix hospital in Raleigh, NC compared to our efforts at Cherry Hospital in Goldsboro, NC. We think about this every day in the Southern Historical Collection, when we compare the paucity of information, we have about enslaved individuals to the information we have about wealthy white families.

During a Spring seminar talk for information and library science graduate students, the poet and activist Anasuya Sengupta explained that often, we are simultaneously oppressor and oppressed. I think about this often while engaging in community-driven archives work. Within Wilson library, I often work with and am surrounded by materials that document the subordination of BIPOC and I sometimes feel dejected by the lack of empowering materials that celebrate black or biracial black experiences.

Brianna McGruder

Sources that explore power

- Revisiting a Feminist Ethic of Care in Archives: An Introductory Note (2021): Caswell and Cifor

- Toward Slow Archives (2019): Christen and Anderson

- The House Archives Built (2021): Berry

2

Radical Empathy acknowledges multiple ways of knowing. Our manuscript collection is full of ink on paper, what if your community does not hold knowledge in this way? What if it is in the oral tradition, the tattoos, or a worn in cast iron skillet, this history matters and confirms that the traditional archive is missing important pieces of the story. We don’t say this to expand the collection scope, we say this with humility and openness to new interpretations of our collections.

In her memoir Bad Indian, California Indian activist Deborah Miranda writes about the pain she experienced in white American schooling where her teachers repeatedly told her that she could not be a California Indian because they were extinct. There was such a deep adherence to this idea that her white teachers felt a need to impress upon a child that her very understanding of herself, her community, and her people was wrong, that she did not exist. Why?

Flannery Fitch

Sources that explore ways of knowing

- Feminist Pedagogy for Library Instruction (2013): Accardi

- Tribal Critical Race Theory in Zuni Pueblo: Information Access in a cautious community (2021): Leung and Lopez-McKnight

- To Suddenly Discover yourself existing: uncovering the impact of community archives (2016): Caswell, Cifor, and Ramirez

3

Radical Empathy is not a moral imperative. We don’t talk about radical empathy to make powerful people or institutions feel bad and share their resources. We hope that a clear identification of the imbalances will help people think about the specific ways that their work helps or hinders progress toward equity. We also acknowledge that there is no silver bullet, and that the other tenants of our understanding of radical empathy will be consulted as decisions are being made.

Celebrating our differences while acknowledging our shared humanity and placing this awareness at the center of our day-to-day activity. Examples of this include asking thoughtful questions, sharing candidly, listening and demonstrating understanding, speaking, writing, and acting with kindness and humility.

Michelle Witt

Sources that explore morality

- Dusting for Fingerprints: Introducing Feminist Standpoint Appraisal (2021): Caswell

- How to be Anti-Racist (2019): Kendi

4

Radical Empathy invokes notions of belonging and community. When we think about communities that have been “othered”, a common part of their resilience is the development of a sense of community for themselves. Archival practitioners can learn more about dignity, truth, and the power of collective memory by listening to and learning from community memory practitioners. In all our discussions we asked, who belongs? who has been excluded? which community is being centered? — to bring our activities and decisions into closer alignment with our values.

White American culture has historically enforced an idea of individualism that strips power from communities and upholds keeping that power with the ruling class. Embracing community is a way to subvert this, because community allows for different viewpoints, experiences, and beliefs while functioning as a whole. Shifting focus from standard archival and library practices into a more community driven, empathetic model not only uplifts the experiences of oppressed and marginalized communities but increases our overall experience of community and how crucial it is to have a place and a people to belong to.

Flannery Fitch

Sources that explore belonging and community

- From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives (2016): Caswell and Cifor

- Each according to their ability: Zine Librarians Talking about Their Community (2018): Wooten

- A Measure of Belonging: 21 writers of Color on the New American South (2020): Barnes (editor)

5

Radical Empathy calls for embodiment, in every sense. Embodied knowledge radiates from our heads and hearts, extends to our surroundings, our nation, and our planet. There are stories that can only be told by certain people because they have lived it, stories that can only be told in certain places, because the natural environment holds so much memory. We give space for our whole selves in our work and think creatively and with deference about how embodiment could be understood by our colleagues and the people in our collections.

Thinking about an archive or artifact as disembodied knowledge, these items that are often mistaken as neutral and natural, and by some audiences deemed as history embodied. A historical document sheds light on the past, through a particular lens and through several (sometimes unknown) facets, producing a particular narrative; but only the person that produced the document embodied the knowledge, and transcribed that knowledge into a now disembodied document. The document can’t talk to me or explain the thinking of its creator. All we are left to do is carefully and cautiously interrogate these disembodied materials with our whole, embodied selves.

Brianna McGruder

Sources that explore embodiment

- Why the Way we Tell stories and Document History as a social justice issue (2019): Mason-Hogans

- This [Black] Woman’s Work: Exploring Archival Projects that Embrace the Identity of the Memory Worker (2018): Powell, Smith, Murrain, and Hearn

- Undrowned (2020): Gumbs

6

Radical Empathy is iterative. We know that a decision that we make today about description, budgeting, or collections could easily be challenged tomorrow. We all have blind spots and finite resources, so we make our best decisions with the information in front of us and try not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

Treating archiving as a living discipline that’s constantly changing

Michelle Witt

I must credit Michelle for introducing me to the idea (really, the fact) of our initiatives as iterative. I’ve discovered that it’s very easy to self-aggrandize through weight-of-the-world mentality in imagining the most ethical, most reparative, most effective initiatives and projects to combat epistemic injustices. But after listening to Michelle’s very wise realization that our efforts are but a step in the direction of progress, I felt relieved! I’ve felt more productive since internalizing the work of reparative archives is iterative. Like meditation, iterative repair and care work seems to be the spot where “intention meets honesty in practice” (Anasuya Sengupta 2022).

Brianna McGruder

Sources that explore iteration

- Radical Collaboration: An Archival View (2018): McGovern

- Archives, Records, and power: the making of modern memory (2002): Schwartz, Cook

Visions for a Community-Driven Archive

Throughout our grant-funded Community-Driven Archives project, our team worked in collaboration with our partners based on a guiding set of values that emphasized community benefit, reflexivity, service, and accessibility. Now that we’ve concluded the work on our grant, we are identifying ways that our short-term efforts can have a longer-term impact on the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill.

What might we take with us into the next chapter? What is our vision for community-driven archives when practiced at scale at an archival institution?

Free from the pressure and limitations of grant deliverables, our team started the process of imagining what our home institution might look and feel like through a community-driven archival lens. Below is a synthesis of some of our team’s conversations.

What might signal a Community-Driven Archives approach to library visitors and researchers?

When a member of the public visits the library’s website or walks in the door of the library, they see announcements about upcoming events that pertain to some of their interests. They see an event invitation to a free community archives scan day at a local community center in partnership with the library. They see an upcoming Archives 101 training and skill-share hosted by an organization they are already familiar with, one connected to their neighborhood, identity, or hobbies—another community-library partnership. They see an announcement that a local community organization received a substantial grant to start a community archive with the support and ongoing partnership of the library. In addition to the library’s website and buildings, they see these announcements and flyers at various community spaces and public places they frequent, as well as through member groups’ web-based communications and social media.

What do these approaches have in common?

- They do not take place at an institutional library setting, but rather at community centers and spaces that our collaborators already frequent and feel comfortable visiting. A public library can feel more comfortable and accessible, for example, than an academic institutional library.

- They are all based on partnership with organized groups of people and and/or existing community organizations, rather than relying on one individual as the “go-between” or trying to recruit community members to attend an event based on a one-time interaction.

- They are based on a model in which the library is resourcing communities, with a focus on historically marginalized and underrepresented communities, through funding opportunities and staff support, rather than funding flowing first to the library and then to communities through library-branded programs.

When using the archives, what evidence might users see of a Community-Driven Archives framework?

When community researchers come into the library they are welcomed and asked if they need any specific help with their research project. They see staff working at the library in positions of leadership who look like them. If they are new library users, they are given a welcome sheet with information that might be helpful both to new archives users as well as to new researchers at the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill. This information is also clearly available and accessible on the library’s website, as well as through a printable PDF distributed to partner organizations. The welcome sheet covers topics like:

- What are the easiest ways to get to the archive?

- How will the library accommodate my access needs?

- How do I search the archive for what I’m looking to find? Who can help me?

- How do I request materials to look through while I’m at the archive?

- Why do I need to leave my belongings in a locker and stay in the reading room when I’m looking through archival materials?

- If I find something that I’m interested in, what are the best ways to keep track of it?

- How can I make a copy of items I find here?

- What are the best ways I can share what I find here with other people?

When searching finding aids, libguides, subject guides and other indexes of collections materials, users are able to search using terms for themselves and their communities that they use rather than outdated or, much worse, offensive terms. Searchable guides that do not meet these parameters might be labeled with content warnings and an acknowledgment from the institution that language found in the relevant guide is inappropriate and has been flagged for remediation. Users are encouraged to bring offensive or harmful language that they uncover through their research along with other access needs to the attention of the libraries’ staff through an anonymous online form and/or paper survey.

On the Carolina libraries’ website and through its communications with its users, the library shares recommendations of community-based digital and physical collections connected to historically underrepresented communities, peoples, groups, and events. It should make these recommendations of community archives projects alongside its own acknowledgement of the internal work that must happen institutionally to redress long-standing gaps and silences in its archives, towards repairing historic erasures.

What are the common threads of this archives experience?

- It centers an accessible archives experience for a broad base of people.

- It is attentive to the hiring practices of the library and emphasizes staff diversity across race, gender identity, sexuality, and ability.

- It owns up to past harms perpetrated by and through archival institutions and clearly communicates the steps being taken towards repair and redress.

- It invites users to share any access needs that will support a fruitful archival experience.

What could library outreach activities look like as part of a Community-Driven Archives experience?

A staff member at a local LGBTIQ center receives a call from a staff member at the library. The library staff person explains that the library has been contacting local groups and organizations to ask them about their work and to learn more about the groups and organizations in their area/region. They explain the resources that the library offers to community groups wanting to document their histories and/or preserve and share their historical materials. Those resources can also be found in a guide for potential community partners available online or as a physical brochure.

The staffer from the center shares the center’s history and what goes on there day-to-day. The library staff person asks if they might be interested in setting up a meeting to talk more about how the library might be able to support the center to share its history with its members and chosen audiences, and they take the next step to set up an in-person or Zoom meeting.

What are the important features of this interaction?

- The caller places the focus on the organization or community group and its history rather than on the services, goals, or interests of the institution. The library staff person wants to get to know groups in the broader community and to serve them — and makes that clear.

- The library does not make promises of support it will not be able to provide and clarifies what it is able to offer through a written list of available services in support of community partners. This list is made available to all potential partners and is kept up-to-date on the library’s website.

- Rather than try to secure immediate interest, the caller makes it clear that they want to spend time on building a relationship with this potential partner over time through physical or virtual face-to-face meetings.

How might our communication about our work shift under a Community-Driven Archives framework?

Library collaborations are branded in a way that cross-promotes our collaborators’ work and organizations. Collaborative projects are not branded with institutional colors, and staff members take steps to avoid colors, fonts, images, and related design choices that signal an academic and/or institutional audience to the exclusion of community audiences. When launching, announcing, or celebrating our collaborative achievements, our institution amplifies the work of our collaborators and directs our audiences to learn more about it. Our institution only takes credit for its share of the work and honors and champions the people, groups, and organizations who made contributions.

When we create communications content, we pay attention to voice, reflecting critically and reflexively on the institutional voice we use when reporting on our community collaborations. We look for ways to respectfully weave in the voices of our collaborators, especially when representing their work or stories. When our collaborators entrust us as stewards of their materials, stories, or collections, we make it a priority to promote those items, so as to reach our collaborators’ priority audiences in addition to our own.

What are the common threads of this approach?

- It requires institutional staff to be reflexive when representing collaborative work, taking into consideration the power of the institution and the benefits, responsibilities, challenges, and problems that come with it. Sometimes it means using the weight of the institution to direct people and resources in support of communities. Sometimes it means amplifying community voices rather than our own.

- It redirects the focus of our communications about our work to serve the goals of our community partners. It pays attention to our partners’ needs rather than those of our institution, donors, or funders. This shift in how we represent our work is communicated upfront to institutional and fundraising stakeholders.

- It makes design choices that signal a shift in our communications towards community benefit.

Reflecting on our Community-Driven Archives Project, 2017-2021

Beginning in 2017, the Community-Driven Archives (CDA) team with the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill’s Southern Historical Collection developed approaches to working with historically underrepresented history keepers that center the needs and goals of our community collaborators.

Our approach has focused on building trust, developing relationships, and valuing process over product. Although some of our collaborators decided to donate their historical materials to the Wilson Special Collections Library, our Carolina libraries staff-led team coached our collaborators to make the decisions that they felt were the right fit for them and their archives. Our goal was to help our community partners make informed choices about how to best care for their collections, whether at home, through a local organization or community archive, or housed at an archival institution like ours.

After four years, our CDA team has concluded its work on this Andrew W. Mellon grant-funded initiative. As we come to the end of our journey together, our staff and graduate student research assistants took the time to reflect on and to be honest about the strengths of this work and the challenges and weaknesses of our project.

A Winning Team

First, all of us have loved being part of Carolina libraries’ Community-Driven Archives team! We emphasize that, because community-based projects are relational and determined in large part by the people doing the labor of connection and care, it really matters who is doing the work. Ours was a Black-led, multiracial, majority women and nonbinary people-staffed project team, including our staff and student workers. We learned so much together and each of us brought a unique perspective as well as personal and professional background. We emphasized clear, honest, and frequent communication, deep listening, and supporting one another in asking questions and growing as people and practitioners.

“I have learned what this type of work consists of. This is my first time ever working in a library and coming into this role, I did not know all of the different type of things that went on in the library. I was so thankful to be included on the team…so that I can continue to learn and grow professionally in this field. I am thankful for everyone on the team for being open and inclusive and I will never forget this experience. I love being a part of something, especially when it involves pouring into a community that once poured into me.”

– Charlissa “Charlie” Rice“I’m most proud of the project’s evolution over the course of the grant. Every graduate student, staff member, and community added a critical element and we grew together. The project transformed from its original conception and became something more real, more transparent, and more inviting, which makes me feel like we have a better chance of achieving some sustainable practices.”

-Chaitra Powell“This is one we don’t really talk about: I am incredibly proud of how diverse our CDAT staff team is/has been. I think we “walk the walk” in that regard. I also reflect a lot on the labor issues we’ve discussed, in terms of how much this work relied on graduate students and term-limited employees.”

-Biff Hollingsworth

Community Collaboration

Doing community-based work from within an archival institution is hard. Institutions are complex systems employing people to sustain them, and they have their own goals, objectives, and measurements of success. Sometimes those align with the goals that communities have for themselves, and sometimes they do not.

Additionally, archival institutions, including UNC-Chapel Hill’s Wilson Special Collection Library, are well-oiled machines; they rely on systems developed over the course of decades or, in the case of the Southern Historical Collection, centuries. Our team has realized that, because of its highly relational nature, community-driven work requires institutional practitioners to spend extra or unplanned amounts of time with a collaborator working through an issue. It often requires that archives professionals to be nimble in a way that our current work structures and systems don’t readily support.

A big question that continues to arise is one around the morality and ethics of grant-funded institutional community archives projects. Do marginalized communities truly benefit when grant funds support staff salaries rather than directly resourcing community-led archival projects? We continue to wrestle with this question, asking ourselves, “What role can institutional archives play in supporting a community’s control over its stories and historical records?”

Despite these challenges, obstacles, and cautions, we feel proud of the work that we accomplished and the ways that our collaborators have been able to build their archives, share their research, and grow their projects and organizations with some added resources and support.

“The EKAAMP exhibition and related gatherings and charrettes felt extremely powerful and like they had a measurable positive impact on the community partners. I’m proud of all the fieldwork we did in the mountains with the [Appalachian Student Health] Coalition; our involvement in the Black Communities Conference; how we supported the recording of oral histories for SAAACAM; History Harvests and in-person workshops; and [Archival] Seedlings!”

-Biff Hollingsworth“I do think in the future, even if it’s not a grant collaboration (but especially if it is), everyone needs to be at the table ahead of time to design the project together before even deciding to do a project…In the future, I think it is OK to start small. Everything doesn’t need to be a big roll out or comprehensive coverage. I think it could be powerful to just focus on certain types of things or even starting close to home in the Triangle.”

-Sonoe Nakasone

Accessibility

One key thing we learned while developing our project is that our work gets stronger the more accessible it is. Accessibility helps everyone, whether it is someone using a screen reader, listening to a video with captions, or simply navigating a website for the first time.

If we want our tools, resources, and programs to reach broad public audiences, we learned that meaningful accessibility is not optional or a last-minute addition; it is baked into the way we do our work. We see access along with anti-racism and other forms of social justice frameworks as integral to community-driven archives.

In 2020, we focused mostly on digital accessibility, from creating alt text for images, to creating audio transcripts, to simplifying our sentences and removing jargon. We are excited to imagine how our approach to access can support the ongoing accessibility work of the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill.

“I feel proud of striving and working hard to make each piece we created or curated accessible and open for everyone.”

-Lidia Morris“I learned so much through this work about access and how it is a healing, liberatory act both to ensure access for others and to experience access individually.”

-Kimber Heinz

Defining Archives

One of the core values of our project has been to demystify archives. Many people don’t know the definition of an archive or its purpose. Part of what we are here to do is to connect everyday history keepers within families, organizations, businesses, and communities of all kinds to resources to help them build or refine their archive, item by item. We hope for our collaborators to see their own materials as archives or archives-in-the-making.

Another piece of the work of demystifying archives is defining the role of institutional archives like ours at Carolina libraries in relationship to communities outside of the institution. We know that we want to advance and amplify the work of historically underrepresented communities, but we have questions about how to best do that without extracting from communities or leveraging our partnerships to attain resources, acclaim, or unearned praise.

“I have learned how to define archives in a way that doesn’t see it as a closed circuit, but an open world ready for input from people who have too often been archived and forgotten. I have come to learn that any archive would be richer, kinder, and more powerful with the people it seeks to define involved in it in any way possible.”

-Lidia Morris“I’m really thinking about the definition of CDA, and what it means to each of us. To me, it is fully situated in our institutional context. Which communities have been silenced by the Southern Historical Collection? How might we start re-aligning priorities and resources to be more inclusive of those communities?”

-Chaitra Powell“I have learned so much about how institutional and community archives function through my involvement in CDA. Learning about institutions through the lens of community-driven archives has taught me that just because something has always been done a certain way, doesn’t mean it’s the right way AND it’s trained me to look for the people, experiences, and events, that are underrepresented or rendered invisible by predominantly white institutions.”

-Alex Pax Cody

Storytelling

Beyond preserving and caring for historical materials, our project has emphasized and supported capacity-building around interpreting these materials and sharing stories. For many of our collaborators, the stories held within their archival collections haven’t been told anywhere else. After building their collection, many of the people we worked with also felt moved to share the stories contained within it with public audiences.

Our team supported our collaborators in creating exhibitions, audio pieces, documentary videos, interactive maps, and public programs as pathways to storytelling.

“The biggest thing I’ve learned is history from our different partners. I’m not a historian or a Southerner, so working with these folks has been so enriching in understanding American history. It’s a privilege, too, because even though their histories are part of some popular threads (e.g., The Great Migration, historically Black towns), the specificity of these communities’ histories has been unknown to a lot of people outside the community.”

-Sonoe Nakasone“Through our work with our collaborators, I learned so much about local histories that I would not have heard about otherwise, including some in my own backyard in North Carolina. I feel honored to be connected to the people steadfastly stewarding these stories for future generations.”

-Kimber Heinz

While our grant project is officially over, our relationships with our collaborators and the lessons we learned along the way remain. Check out our new Community-Driven Archives project website to explore more of our work and reflections on archival institutional support for community-based archives.

The Community-Driven Archives Project at UNC-Chapel Hill is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Follow us on Twitter: @SoHistColl_1930 #CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC

Community Archives as Data: Reflections on Oral History Text Analysis within the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project Archive

Between September 2020 and January 2021, I worked on an EBSCO-funded internship administered through the Association of Research Libraries focused on a Python text analysis project on oral history interview transcripts. I worked with the Community-Driven Archives team, which partnered with communities across the American South to amplify histories that have been silenced or marginalized in traditional archives. The purpose of this project was to explore the possibility of using computational methods on oral history data. I was interested in exploring how computational methods can build upon digitization, in which historical records are searchable on the web, to make community archives more accessible to their respective communities.

My project focused on oral histories created by the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project (EKAAMP), a public history and community archival project centered on the stories of Black former coal mining families in Eastern Kentucky. The Community-Driven Archives team collaborated with EKAAMP to support the creation of its collection, some of which is housed in the Southern Historical Collection at University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill, along with a series of traveling exhibitions. EKAAMP honors the place of Black Americans in Appalachia.

Learning Text Analysis in Python

Python is a powerful programming language. Aside from its extensive use in software and web development, Python is also widely used in computing and applying computational methods to humanities and social sciences data because of its powerful data modeling libraries and natural language processing algorithms. One such application is text analysis, where a body of textual data is processed and analyzed. When done well, text analysis can reveal patterns in topics and sentiments in large quantities of textual data.

I started this project being very new to the world of text analysis and to Python as a programming language. I used a variety of resources in my self-directed and explorative learning process, both on Python and on text analysis methodologies. Here are some of the resources that guided my project and helped me respond to challenges along the way:

- Your Guide to Latent Dirichlet Allocation: https://medium.com/@lettier/how-does-lda-work-ill-explain-using-emoji-108abf40fa7d

- How to Generate an LDA Topic Model for Text Analysis: https://medium.com/@yanlinc/how-to-build-a-lda-topic-model-using-from-text-601cdcbfd3a6

- Introduction to Latent Dirichlet Allocation: https://blog.echen.me/2011/08/22/introduction-to-latent-dirichlet-allocation/

I found the following text analysis projects and papers informative and relevant to this project:

- In Search of the Drowned in the World of the Saved: Mining and Anthologizing Oral History Interviews of Holocaust Survivors: https://dh2018.adho.org/en/in-search-of-the-drowned-in-the-words-of-the-saved-mining-and-anthologizing-oral-history-interviews-of-holocaust-survivors/

- A brief digital humanities discussion on analyzing oral history interviews from audio recording files: https://www2.fgw.vu.nl/werkbanken/dighum/data_analysis/text_analysis/ta-introduction.php

- Oral History and Linguistic Analysis: A Study in Digital and Contemporary European History: https://ep.liu.se/konferensartikel.aspx?series=ecp&issue=159&Article_No=2

I learned that most resources and available projects utilizing text analysis deal with bodies of text that are different than oral histories, both in content and structure. For instance, the conversational format of the interview transcripts meant that the more common text analysis techniques that are used on other kinds of texts will not yield meaningful results. Based on what I learned in my research, I explored two main text analysis methods, including Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), to categorize main topics discussed in the interviews.

My preliminary results yielded by the LDA methods aligned with the main topics covered in EKAAMP and Dr. Karida Brown’s research related to these histories. Some of the main topics that emerged in the text analysis results were: family reunions, school integration, and mining accidents.

Archives as Data: Computational Methods for Community Archives

In support of the larger work of the Community-Driven Archives project, I wanted to explore the research value of archival collections, such as oral history transcripts, as data that can be analyzed and visualized through computational methods. My goal was to gain deeper insight into these histories through text analysis, an automated process for gaining insight into a large collection of oral history interviews by mapping common topics and visualizing patterns in conversations. Such computational techniques would then be used to extract a variety of data about the collection as a whole and about individual interviews. This would support community researchers’ discovery and identification of these histories.

This model can then be built upon and implemented in the future for metadata generation for collections with similar size and scope. High quality metadata that provides descriptive information about an oral history collection not only facilitates better discovery and identification, but also creates exciting possibilities for presenting and analyzing the research data, such as data visualization of migration paths among Black former coal mining families represented in EKAAMP oral histories.

Perhaps this project can serve as an example of using computational tools and techniques for unlocking data and gaining insight into large oral history collections. Community leaders in charge of similar public history projects can use such tools to reimagine discovery, management, and description of their oral history archives.

I am in the final phases of developing a website to open source my code for the public to use and build upon. The website will include a brief collection description, as well as a brief discussion of challenges and snippets of Python code to run on an internet browser.

Data analysis methods and techniques can transform large quantities of non-machine-readable content, such as oral histories, into machine readable content. This transformation would enable community leaders to enhance their archives by creating robust research data sets for computational research. The new data would then allow community researchers to present, visualize, and analyze oral histories in new and dynamic ways.

All Hands on Deck at Hobson City’s Museum: Interview with Pauline Cunningham

In August 1899, the determined leaders of Mooree Quarters, the Black neighborhood of Oxford, Alabama, formed a separate town: Hobson City. It would be the first incorporated Black municipality in Alabama and the second in the nation.

Over the next several decades, Hobson City developed into a magnet for Black excellence and entertainment in the South. Today, Mayor Alberta McCrory wants to share the remarkable history of Hobson City and other historic Black towns in Alabama at the Hobson City Museum.

Through a partnership with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries’ Community Driven Archives (CDA) project, Hobson City Museum hosted a workshop in March 2020 that focused on caring for museum collections. Three UNC Libraries staff members provided training to residents of Hobson City and nearby Anniston on how to clean, handle, store, and inventory plaques, textiles, trophies, and photographs that document the contributions of local leaders such as James “Pappy” Dunn. Town Hall Clerk Pauline Cunningham was the Hobson City coordinator for the workshop and also participates in another CDA archival training program called Archival Seedlings. I met with Pauline over Zoom to reflect on our collaboration in March and the future of the Hobson City Museum.

Conversation with Hobson City, Alabama Collaborator Pauline Cunningham

Q: What is the purpose of Hobson City Museum?

Pauline Cunningham: To be educational and show the history of Hobson City and who was all involved in making a change in Hobson City. We started with [James] “Pappy” Dunn because he invested so much time, money, and energy in making a change for Hobson City.

Q: Who do you see as the visitors, and what kind of information do you hope they get out of it?

PC: We want people from all over—all over the United states, all over the world—to be able to come, see, learn, and understand the struggle that Hobson City has had in the past; and maybe in due time we’ll also show the struggle that’s happening right now. Not because of COVID-19, just because of the economy.

Q: What was the museum’s goal for the workshop in March, and was it met?

PC: Not knowing anything, I feel like we learned so much. We learned how to archive, how to clean with the right agents. We learned how to do so many things. How to preserve. It was so educational. I think my downfall is going to be, the people [who] were there this year to learn, [they] might not be there when [COVID-19] is over. I plan to try to write everything down and to make what we call a SOP [Standard Operating Procedures] for the military—how to do each step. I would love to add a DVD to it with all the videos that we had when learning from the different presenters [our series of how-to webinars through the Archival Seedlings program].

Q: The workshop happened as COVID-19 cases started to spread nationally. How did COVID-19 affect the museum in March? How has it continued to affect the museum?

PC: It really went to a standstill. I’m older. I’m in that population that you don’t need to be out there unless you have to be, so it really went to a standstill; that’s the bad thing. The good news, I guess, will be once I start doing the SOP [manual], maybe somebody else can pick it up and keep doing some things; but right now, we’re at a standstill because of COVID-19.

Q: What do you think is the number one challenge going forward with skills gained through the workshop?

PC: The memory that I won’t have if I don’t write it down. And the challenge is going to be getting the right people to continue to help with the museum, even though it doesn’t seem like a large project to some people. But it’s getting that volunteerism to come out and help—to work for the City, to get the City up and running—and I believe those that decide to do it, they’ll do it from the heart. So that’s going to be my challenge: to find the right people to make it continue to go.

Q: Should those people be in the community or people outside?

PC: Both really. Reality: when you guys were down in March, everybody there except for two people were from outside [Hobson City]…including myself [Pauline is a resident of nearby Anniston, AL.].

Q: What is the number one challenge of the museum?

PC: Space…availability for the museum. The challenge is going to be to utilize the space the best way to display or to show what we want to. Part of it [is] going to be the videos of people talking about the history, and some of the pictures, and some of the stuff we’ll just scan to make the rotating [slideshow] and voice behind it—where it came from, who donated it, and why it’s important—that sort of thing. That’s the challenge—putting [in] the right mix for such a small space.

Q: What was your favorite part of the workshop?

PC: I have two: One was archiving and learning how to do it right, so you can go back and find it on your archive list and where you stored it. And two was the cleaning of the artifacts. That to me was very critical because I would have messed it up! Because I would have used some regular cleaning detergent type stuff. So that—those two—how to store and clean and archive, that was tremendous. I loved it. I loved it.

Q: What question do you wish I asked you? Is there more you’d like to say?

PC: Just that I want to make sure I’m able to put the SOP [manual] together on how to do each thing. If I die tomorrow, somebody else can pick up the ball and run with it and know how to do it right. If I can pull all that together, I would love it. It’s a win-win for the City and for the education provided to us.

Want to learn more about Hobson City? Visit the town website and watch the documentary Hobson City: From Peril to Progress, 27 min, by Hiztorical Vision Productions.

Read more about our work in collaboration with Hobson City, AL and other members of the Historically Black Towns and Settlements Allliance (HBTSA) on the Southern Sources blog:

The Community-Driven Archives Project at UNC-Chapel Hill is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Follow us on Twitter @SoHistColl_1930 #CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC

Oral History Resources

![]()

Oral History Resources

Oral histories are an essential part of most Community-Drive Archives work. Through oral histories, we are able to hear directly from people who have important stories or memories to share. Oral histories enable different ways of thinking about and learning from the past, and often present perspectives that are not well represented in traditional museums and archives.

One of our key partners at UNC-Chapel Hill is the Southern Oral History Program (SOHP). Since its founding in 1973, the SOHP has done groundbreaking work, creating a vital record of Southern history. The SOHP is often recognized as one of the leading oral history programs in the country. They are also a terrific resource for learning more about doing oral history, whether you are a seasoned professional or if you’re getting ready for your very first interview.

Here are several resources that we have found helpful when planning or preparing for oral histories:

- If you’re looking for basic tips, the SOHP’s 10 Tips for Interviewers is a quick overview of important things to remember when you’re doing an interview.

- For a more detailed guide, the SOHP offers “A Practical Guide to Oral History,” a very helpful overview that will help you get ready for your first interview.

- For suggestions specific to interviews with members of your family or community, “The Smithsonian Folklife and Oral History Interviewing Guide” is a helpful resource.

- If you’re simply looking for ways to start talking or to keep the conversation moving, be sure to download a copy of the oral history question cards prepared by UNC’s Community-Driven Archives Team (you can also find copies of the cards in our backpacks).

- Finally, if you’d like to listen to or read completed oral histories, you can find the archived recordings and transcripts from SOHP interviews in the Southern Historical Collection at UNC.

- Bernetiae Reed, one of the Community-Driven Archives project staff members, is an experienced oral historian and offers an essential bit of advice for anyone considering oral histories: just get started.

“Don’t wait! Ask your questions now. If you procrastinate that opportunity can pass by and that story, that connection, or that moment could be gone forever! Pull out your recorder during special moments. Seek that person with things you want to know or that person with memories you want to capture. Your actions allow these words to be heard by future audiences! Start with those family stories that you have grown up hearing, connect with community members who have recollections that need to be preserved, and then go on from there. The most important factor in successful oral history capture are a communicative interviewee and an engaged interviewer.”

Ronney Stevens from SAAACAM in San Antonio TX shares a memory of going to the Carver Library as a child.

As you continue on your work with oral histories, no matter where you are in the process, get in touch with us if you have any questions or just have stories to share.

The Community-Drive Archives Project at UNC-Chapel Hill is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Follow us on Twitter @SoHistColl_1930

#CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC

#WilsonLibrary #UNCLibraries

#EKAAMP #HBTSA #ASHC #SAAACAM

#yourstory #ourhistory #oralhistory #AiaB

What’s with all the Backpacks?

![]()

If you’ve seen any publicity about the Community-Driven Archives grant, you’ve probably seen references to “the Backpacks.” One of the central initiatives for the CDA Team is transportable archiving kit that demystifies the technical jargon and supplies resources for communities. This has manifest as the “Archivist in a Backpack” and the slightly less catchy but equally important “Archivist in a Roller bag.” These are a simplified archive in an easily portable kit that we bring and mail to communities doing archival and cultural heritage projects. In April of this year, the online forum HyperAllergic published an article about our “Archivist in a Backpack” project. Since then, we have had an enormously positive response from people all over the world and I think the speed and reach of the backpacks has surprised us all. We’ve received numerous inquiries about the backpacks and our grant project in general. This might seem like a basic administrative detail, but when you consider that each inquiry has the potential to become a new resource and an introduction to dozens of new colleagues, it is no small feat in networking. While most of my conversations have been with people in the US, we’ve had interest all over the globe. From a member of a Canadian first Nation, to a library in New South Wales, an Archivist in the UK doing her own community work with immigrant Somalian communities and a theatre professional in Germany, something about the Backpack project has struck a chord. A version of the backpack has been used in Mexico with Yucatán Mayan students with materials being translated into Spanish and Yucatec Mayan. For more information about this project check out this National Geographic article!

Sounds great, but why all the hoopla? Backpacks aren’t exactly cutting edge. I think it is the mix of the un-apologetically bright colors of the kits (though we do offer some more muted tones) and the awe that digging into a family or community’s past almost always elicits. But there are other components to the backpacks, not always mentioned in the emails. Social justice, commemoration, and community healing often feel like implicit threads of the conversations and the projects new colleagues talk about.

Sounds great, but why all the hoopla? Backpacks aren’t exactly cutting edge. I think it is the mix of the un-apologetically bright colors of the kits (though we do offer some more muted tones) and the awe that digging into a family or community’s past almost always elicits. But there are other components to the backpacks, not always mentioned in the emails. Social justice, commemoration, and community healing often feel like implicit threads of the conversations and the projects new colleagues talk about.

The backpacks look unimposing, but I think they represent something quite profound. The backpacks invite people to tell their histories so that the information can be put towards a larger purpose. The backpacks aren’t just about a walk down memory lane (as important as that is) but many of the people with whom I’m in contact have a mission that the archival resources are to be used in forwarding. Whether it’s about connecting generations in learning about the many iterations of civil rights, housing and preventing gentrification and displacement, or combating rampant minority stereotyping and erasure practices, the backpacks are an accessible way for communities to take control. The initial emails show that many projects are just getting off the ground or are still in the early planning stages. It will be interesting to see what the results are for everyone, especially since we at CDA are right there with them. It’s a “figure-out-as-you-go”, one foot in front of the other kind of process, collaborating between institutions, communities, and newly-found colleagues. At least we can all have coordinating backpacks.

We post every week on different topics but if there is something you’d like to see, let us know either in the comments or email Claire our Community Outreach Coordinator: clairela@live.unc.edu.

Follow us on Twitter @SoHistColl_1930

#CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC

#EKAAMP #HBTSA #ASHC #SAAACAM

#yourstory #ourhistory #community #AiaB

What is a Charrette?

![]()

A charrette is a focus group that brings together a wide variety of stakeholders in order to map solutions. Originally used in the Public Health field, our CDA Team and others have borrowed the term for community and cultural heritage work. Our charrettes bring individuals together to collaborate and workshop ideas for a common community vision. We focus on topics such as promoting and protecting cultural heritage, telling underrepresented histories, and discovering archival assets in communities. For our CDA team, we collaborate with a diverse group of stakeholders and individuals such as funders, librarians, community members, professors and academics, town officials, activists, artists, and archivists. These diverse participants ensure that the charrette isn’t an echo-chamber. Rather, members share a desire to invest in and protect a community but from different angles and perspectives.

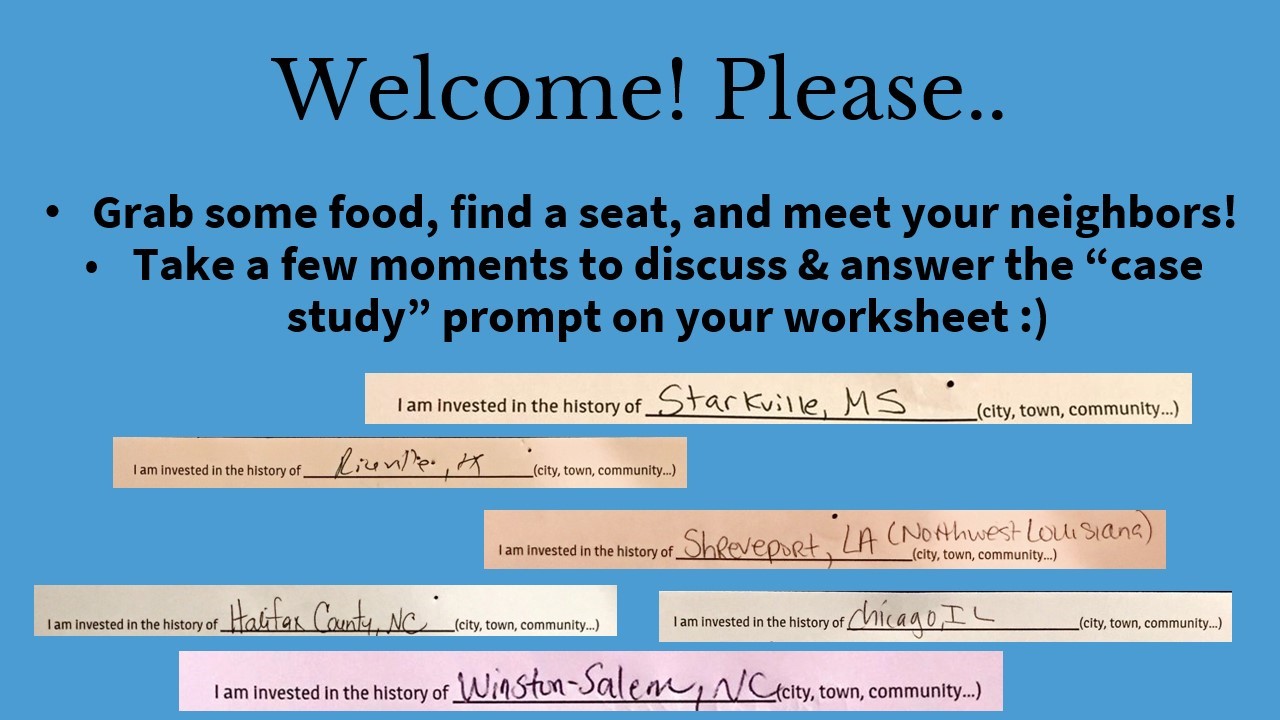

A good charrette invites community expertise and specific knowledge of the historical and cultural dynamic; members within the community know the needs far better than we ever could. A common and often deadly shortcoming of any institutional project is to assume the institution knows what’s best for the community. Equally devastating is when an institution has a real desire to participate but struggles to have meaningful, sustained engagement. Both examples lead to institutions flailing in a sea of uncertainty and ineffectiveness. Charrettes are one way to counter these outcomes. It can be eye opening and humbling to have community members speak to historic problems and instances of broken trust face to face. For the charrette hosted by CDA in April at Black Communities: A Conference for Collaboration we asked individuals to share their knowledge of an African American community, its needs, and some hidden history highlights.

Our charrette was an informal lunchtime meeting. We provided a worksheet (with consent form to use the data collected included!) with a few questions, each probing a little more deeply into the needs and histories of communities. These questions asked participants to identify a place and describe how history is either being preserved or ignored. Our focus was (and remains) geared towards archival and cultural heritage so our questions related to storytelling and preservation of histories and materials. Our first question asked participants to identify a place and a little-known history from that area. Some of the towns and communities identified were Starkville, MS, Riceville, TX, Shreveport, LA, Halifax County, NC, Chicago, IL, and Winston-Salem, NC. Some participants told their family’s history while others focused on broader groups such as the Indigenous peoples and industries.

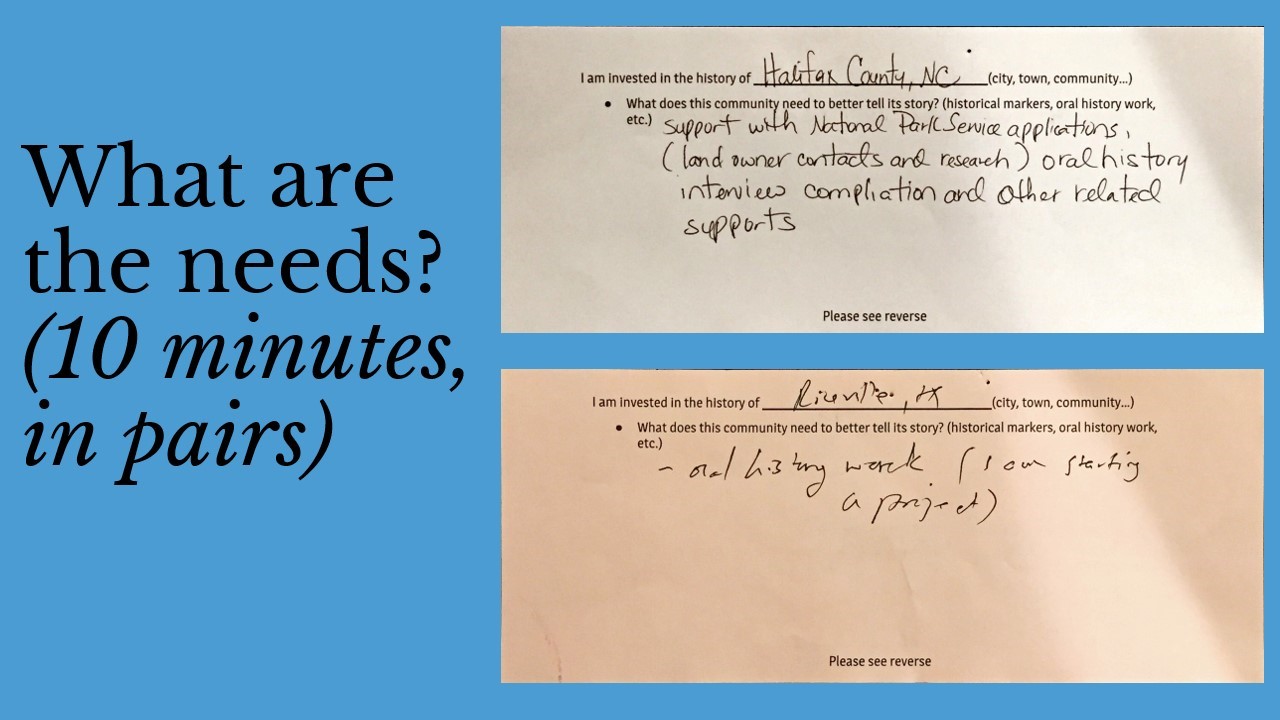

The second question was “What does this community need to better tell its story?” One participant from Halifax County, NC wrote: “support with National Park Service applications, (land owner contacts and research) oral history interview compilation and other related supports.” Another participant interested in Riceville, TX noted that their community need “oral history work” and a project to address that was underway.

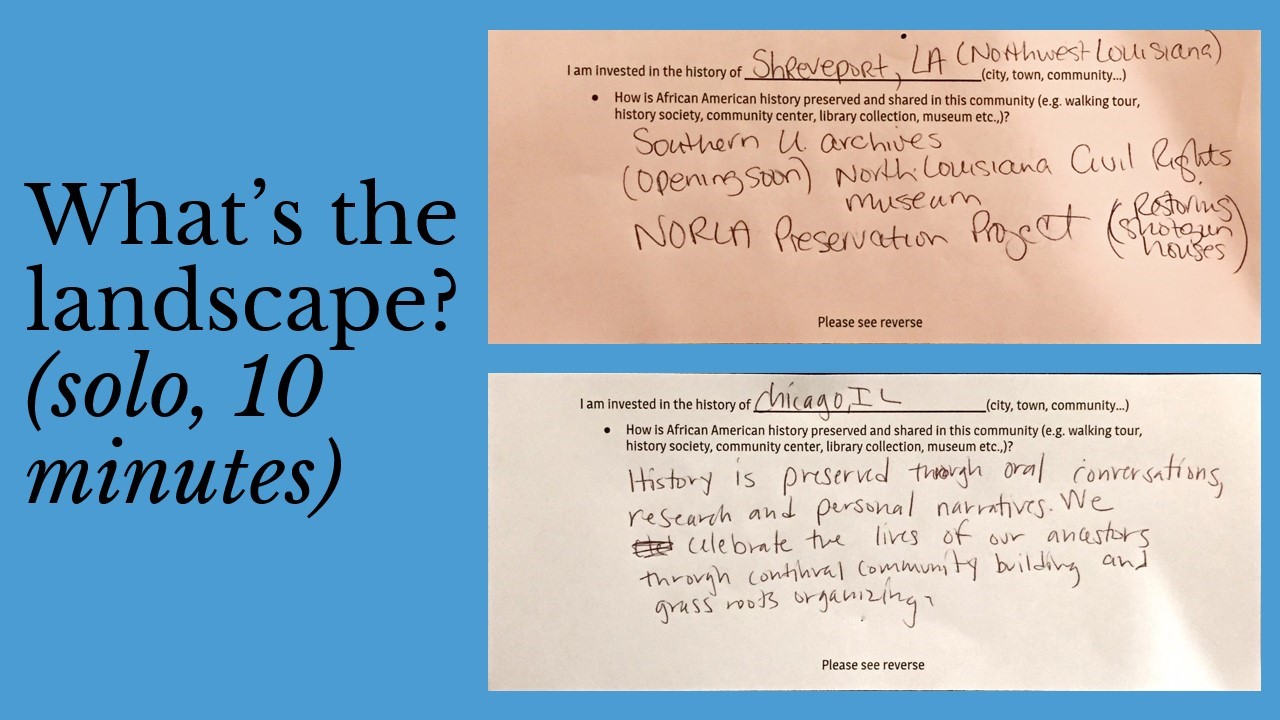

The third question asked specifically “How is African American history preserved and shared in this community?” A participant from Shreveport, LA wrote “Southern U archives, (opening soon) North Louisiana Civil Rights Museum and NORLA Preservation Project (restoring shotgun houses).” Another participant from Chicago IL stated “History is preserved through oral conversations, research and personal narratives. We celebrate the lives of our ancestors through continual community building and grass roots organizing.” The emphasis on in-person communication is something that a charrette works hard to emulate and build upon.

Our final question asked to identify next steps. Preservation is important, but it must lead to something. We wanted to know how the ideas from this charrette could inform not only our work but work within the community. Charrettes can be all day affairs or an hour, like ours at Black Communities. Charrettes are connective, collaborative, exploratory and possibly explosive. All these attributes indicate that these types of in-person focus groups are necessary to identify need and ultimately movement. As one participant perfectly summed up, “information has to drive advocacy.”

We post every week on different topics but if there is something you’d like to see, let us know either in the comments or email Claire our Community Outreach Coordinator: clairela@live.unc.edu.

Follow us on Twitter @SoHistColl_1930 #AiaB #yourstory #ourhistory #communityarchives #EKAAMP #HBTSA #SHC #SAAACAM #memory #community #CDAT #Charrette #activism

What is a Community?

![]()

Here at CDA, our team speaks about communities a lot, working to imagine and redefine what that word implies. But what exactly do we mean when we say a Community? That question seems straightforward but there is a great deal of ambiguity in this term. When we at CDA talk about communities, we aren’t just talking about towns that exist right here, right now with a neatly registered zip code. Communities can be towns, cities, parishes, neighborhoods or enclaves, rural and urban, but they can also be identities, small groups, diasporas, and informally established. Some are “post-place” but still united by a common identity. In other words, there was a historic place, but now it’s a group of dispersed people.

This complex relationship between physical space and abstract meaning produces important discussions about identity, motivating community partners and community champions to combat what scholars like Michelle Caswell have called “symbolic annihilation.”[1] Communities that had been historically, and continually, marginalized, erased, and ignored are finding ways to increase their visibility through community-archival and cultural heritage work. This increased visibility showcases the three parts of what Caswell et al calls “representational belonging.” These three parts, we were here, I am here, we belong here, affirms the importance of a community’s existence.[2] Gaps in the narrative of underrepresented communities affect histories and have consequences for contemporary identities. By refocusing the narrative, communities control their own modes of representation as opposed to tokenism by traditional power structures.

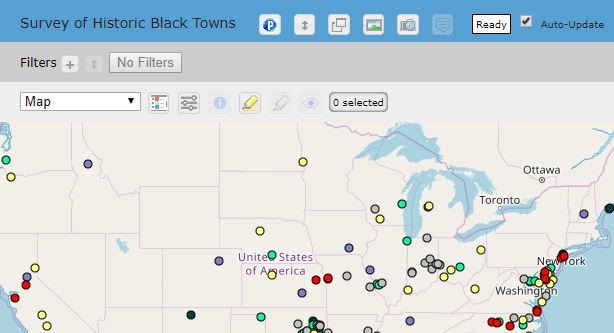

Here are a few examples of why representational belonging is so important. Shankleville is an un-incorporated community in Newton County, Texas. This was a “freedom colony” founded by Jim and Winnie Shankle in the postbellum period. What does it mean for the contemporary community that lives in and studies Shankleville that there are so many gaps in the narrative about the lives of Jim and Winnie? Another community example is found in Portland, Oregon. One community member talked about the invisibility of the Black community there, especially when paired with notions of gentrification and infrastructure expansions, like a light-rail that displaced large swaths of the African American community. Local organizations, like the Vanport Mosaic, use art and other media to amplify forgotten histories, but what do the historic erasure practices mean for those living in the Pacific Northwest? A final example is the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project which examines the now diasporic community previously located in Lynch, KY. As jobs in the coal mining industry dried up in the mid-20th century, families relocated physically, but they remain deeply connected to Harlan County and each other. What does it mean for miners, children and grandchildren of miners to be so far apart across the country, but to return yearly for reunions? All these communities are striving for representational belonging, internal and external confirmation that their stories matter.

This is one of our grant project data visualization maps, showing the locations of just some historic black towns and communities. There are plenty of places and communities that remain hidden and part of our work is to present as full and as rich a representation as we can based on the materials presented by communities.

We post every week on different topics but if there is something you’d like to see, let us know either in the comments or email Claire our Community Outreach Coordinator: clairela@live.unc.edu.

Follow us on Twitter @SoHistColl_1930 #AiaB #yourstory #ourhistory #communityarchives #EKAAMP #HBTSA #SHC #SAAACAM #memory #community #CDAT @vanportmosaic @shankleville

[1] Michelle Caswell, Alda Allina Migoni, Noah Ceraci, and Marika Cifor, “‘To Be Able to Imagine Otherwise’: community archives and the importance of representation,” Archives and Records, 38., no. 1, (2017), 5-26.

[2] Caswell, et., al.