Over the past several decades, UNC woman’s athletics teams have had an incredible run of success, winning multiple NCAA championships in five different sports. However, it was just 50 years ago this month that UNC offered its first athletic scholarship to a woman athlete.

During the 1974-1975 season, women’s tennis coach and newly appointed Director of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, Frances Hogan, drafted a note for her team about the evolving standards for women’s sports at UNC. In the memo found in a folder for the 1974-1975 Tennis season, she wrote:

Up until 1971, the philosophy of teams, or clubs as they were called, was to provide opportunities for a sociable, competitive experience… Women coaches have been oriented that way. We can no longer, as coaches, maintain this philosophy. We are now in athletics. A great amount will be budgeted for our women’s program from the athletic department next year. Coaches will have to look for the best players. . . . Recruiting is legal. Demands on the coaches will be greater. They must produce good teams to justify the money going in to the program.

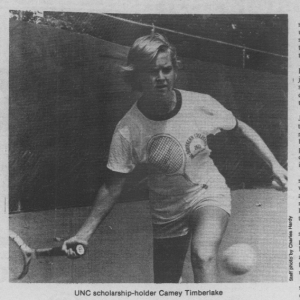

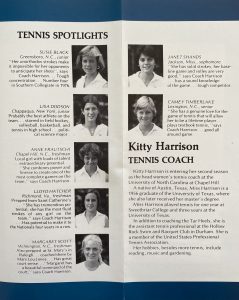

This change from clubs to teams largely began with the passing of Title IX in 1972. Like most large scale social and political changes, the actual implementation comes in stages and looks different in different contexts. There were many local factors that impacted how things would change at UNC. One impactful moment came in 1974 when the first UNC women’s athletics scholarship was awarded. At the time, the scholarship was called a grant-in-aid. That awardee, Camey Timberlake, was a talented high school tennis player who would join the UNC squad in fall 1974.

As Hogan’s note to the 1974-1975 team highlights so well, the pressure on UNC women’s athletic teams to show up for this moment was real. And the pressure on Camey Timberlake was not wholly different. It was time to perform to win and keep the momentum for women’s athletics.

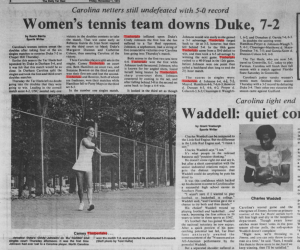

Timberlake’s tenure at UNC included highs like beating Duke’s star player as a first year and lows like injuries that sidelined her more than once over the years. Disappointments are part of sports and those that play at the highest levels know that better than most. In an interview with the Daily Tar Heel in April 1978, she gave voice to the pressures she felt during her seasons with Carolina noting, “I had decided I wasn’t going to let the pressure bother me, but subconsciously, it was there, and there wasn’t much I could do about it.” While Timberlake’s playing experience at UNC may not have been as she had hoped, she emphasized the positive impact her fellow teammates had on her experience. Timberlake was inducted into the North Carolina Tennis Hall of Fame in 2000.

On the other end of this pivotal moment, UNC continued to reshape the role of women’s athletics at the university in line with Title IX. Ahead of final Title IX regulations for athletics to be released in 1975 and requiring implementation by 1978, Chancellor Ferebee Taylor took proactive steps in 1974 to set the stage for change. The women’s athletic programs were moved into the Department of Athletics and Coach Hogan’s new role, Director of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, was created. Chancellor Taylor also charged a new committee focused on equal opportunity for women at UNC called the Title IX Committee and Subcommittee on Athletics. (Jackson, p. 92; 134- 137). Building on the first women’s athletics scholarship, the second scholarship recipient, Ann Marshall, became a member of the UNC swim team beginning in 1975. Marshall made the 1972 Summer Olympics team as a teenager and was named an All-American 18 times while at Carolina.

The path to women’s athletics at UNC was certainly not without challenges and some resistance. And to this day, all issues of equity and opportunity in women’s sports generally are far from settled. However, it’s still inspiring to consider these beginnings at UNC and see the line that can be drawn to all that has come after. We can celebrate the place that these early scholarship awardees made for so many other talented Tar Heels like Mia Hamm, Charlotte Smith, Shalane Flanagan, Ivory Latta, Erin Matson and countless others as well as opportunities for coaches like Karen Shelton to build programs of the highest quality to cheer for.

Images of documents from the Department of Athletics records:

References

- For a more complete picture of the years long development of women’s athletics at UNC and Title IX context, check out this dissertation by Victoria Jackson. https://keep.lib.asu.edu/items/153493

- You can peruse old issues of the Daily Tar Heel here for lots of sports stories and highlights: https://www.digitalnc.org/newspapers/daily-tar-heel-chapel-hill-n-c/

- Swimming: 1975-1976 season: General, Box 27, in the Department of Athletics of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40093, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Tennis: 1974-1975 season: General, Box 28, in the Department of Athletics of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40093, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Read the entire memo from Coach Hogan here: HoganTeamMemo-1974-1975

- Tennis: 1974-1975 season: Camey Timberlake, Box 28, in the Department of Athletics of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40093, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.