After working its way through the Missouri state and federal courts, the landmark case Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada challenging segregation in higher education came to a close in 1938. In December of that year, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that Lloyd Gaines had been unfairly denied admission to the University of Missouri Law School because he was Black. When Gaines first challenged his rejection, the University offered to pay for him to attend law school outside the state. Gaines’ lawyer, Charles Hamilton Houston, masterfully convinced the courts that if Gaines could not attend the University of Missouri, the state would have to build a law school for Blacks equal to that of whites, recalling the “separate but equal” doctrine laid down in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. The decision was to enroll Gaines at the University of Missouri.

That year, in 1938, with the Gaines decision clearly having created fissures in the walls of Jim Crow, Black students continued pushing on the walls surrounding UNC. In late 1938, Pauli Murray applied to UNC’s graduate school and was denied. Her subsequent exchange with President Frank Porter Graham reveals both her genius and the tenuousness of Graham’s liberal position on race and integration.

Another Black woman applied earlier that year in 1938. Her name was Edwina Thomas. Her exchanges with Frank Porter Graham and Dean W.W. Pierson can also be found with Pauli Murray’s via the Records of the Office of the President of the UNC System Frank Porter Graham (1932-1949). When Thomas wrote to UNC asking the Dean for an application, the Gaines case had not yet been decided, but she was certainly very well aware of the details of the case and its chances for success.

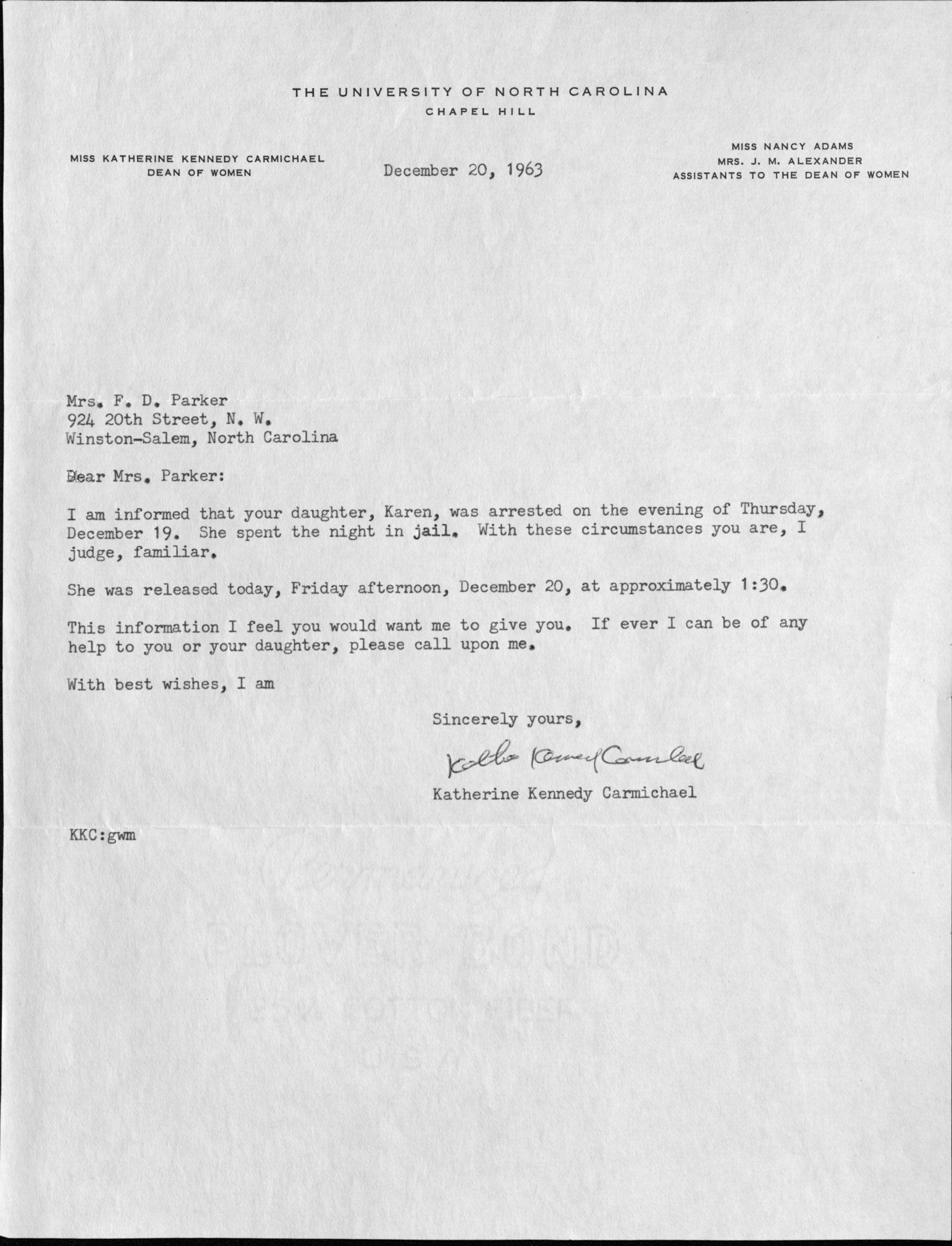

In January of 1938, Edwina Thomas, student at Talladega College in Alabama and of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, applied to graduate school at UNC. She requested an application by mail, which she filled out and returned. It is very unlikely that applications to the University asked for race – surely it was just assumed all applicants would be white. It appears to have taken some time for the Dean to realize that Thomas was Black. Pierson responds to Thomas at Talladega, dated April 27, 1938: “It is my understanding that it is the public policy of the State of North Carolina and the University of North Carolina not to admit members of the colored race to the University. Such admission would entail a reversal of a social policy of long standing and would require action to that effect by the trustees of the institution. I withhold therefore a ruling as to your academic eligibility for admission.”

In May, Thomas writes directly to President Frank Porter Graham, with echoes of the Gaines case in her response: “As I am unable financially to cope with the expenses of graduate schools outside my own state, I should like very much for you to advise me as to just what I can expect from the State of North Carolina in the way of help financially if I am to be denied admission to the State University because of my race.” Graham does respond to Thomas, assuring that despite the “laws of North Carolina with regard to providing separate schools for the two races, and the long established public policy of the state, I took the matter of your letter up with the Governor of our state,” and that the General Assembly should discuss the issue at some point the next year.

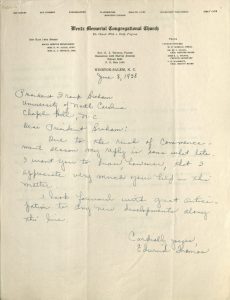

In June 1938, Thomas writes Graham again, and on the letterhead of Wentz Memorial Congregational Church, where her father was Reverend. Referring to any possible decisions made at the state level regarding admission or funding of Black education, she says, “I look forward with great anticipation to any new developments along this line.”

Undeterred, Edwina Thomas still presses President Graham, writing from her home in Winston-Salem in August 1938, indicating that she is very much aware of legal and political tides within North Carolina: “Since a special session of the state legislature has been called, I was wondering the problem of facilities for negro graduate students could not be presented at this time. If this matter could be disposed of during this special session it would be considerably helpful for students, like myself, who wish to attend graduate school next year (next school year).” She closes, “I do hope that this very pressing problem can be mitigated soon.” Graham responds with news that neither education funding nor admission of Black students were discussed at the special session and would not be revisited until January 1939.

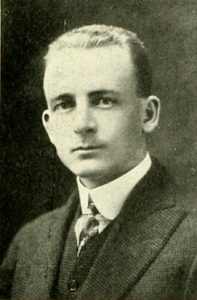

This is the extent of correspondence between Edwina Thomas and UNC administrators. She would not waste time waiting and went on to graduate school at Ohio State. Engaged as a scholar and leader, she became a lifelong member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority. It is not clear if Graham took Thomas’ case specifically to the Governor at the time, as he claimed. The result would have been predictable, as Governor Clyde Hoey was a virulent segregationist and white supremacist.

Edwina Theolyne Thomas was born in 1918 in Alabama to parents the Reverend George Jefferson Thomas and Winnie Cornelia Whitaker. Edwina’s father, originally from Georgia, was the leader of Winston-Salem’s Wentz Memorial Church, a Congregational Church. Before taking over at Wentz in 1924, George Thomas had been the field superintendent for Congregational Churches in Georgia and the Carolinas. When Thomas applied to UNC, she was 20 years old. A few years later when Thomas was 22, she married attorney H. Alfred Glascor, of Columbus, Ohio, and they lived some time in his hometown. Her marriage ended and she moved to Wisconsin, where Thomas became a renowned clinical psychologist at the Milwaukee County Memorial Hospital, a position she held for more than twenty years. There, she formed its first hospital outpatient unit in 1949. Tragically, Thomas died in a car accident in 1968 at age 50, and was mourned by the Milwaukee Star newspaper with a poem, “The Milwaukee Star mourns the loss/Of such an asset to our community;/But realize that one who lived so well/Will continue in the hereafter with impunity.”