At the University Day celebration on October 11, 2016, Chancellor Carol Folt announced a new program to name scholarships after notable “firsts” in UNC history. In recognition of the individuals recognized as pioneers at UNC, the University Archives is publishing blog posts with more information about each of the twenty-one “firsts.” This post is part of that series.

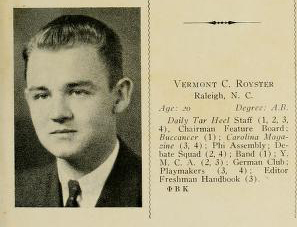

When Vermont C. Royster began his studies at UNC in 1931, he was no stranger to the campus. He was born in Raleigh, and his father, Wilbur Royster, was a professor of Greek and Latin at the university. Although Royster did receive his degree in Classics, his mark on UNC as a student, alumnus, and professor was made through his journalism — writing for the Wall Street Journal and later teaching at the School of Journalism. Royster was one of the first UNC alumni to receive a Pulitzer prize in 1953 (the same year as W. Horace Carter), and he later received a second Pulitzer in 1984.

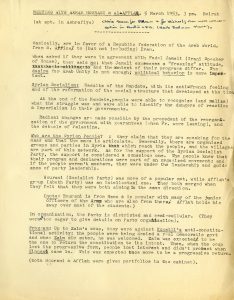

Royster began his journalism career at UNC, where he worked for several campus publications, including The Daily Tar Heel and The Student Journal. During his senior year, he revived and wrote a column in the Daily Tar Heel titled “Around the Well,” which highlighted and described various campus happenings and gossip.

In addition to being drawn to journalism at UNC, he was also an active writer and participant in the Department of Dramatic Arts. As part of a play-writing course, he wrote and staged two plays — Shadows of Industry and Prelude — both of which can be found in the archives.

After graduating, Royster went on to begin the journalism career for which he is well known. He moved to New York and began working for the Wall Street Journal in 1936. He retired from the Wall Street Journal in 1971 and joined UNC’s School of Journalism as a faculty member later that year. Over the course of his career — both as a professional journalist and university professor — he won two Pulitzer Prizes: the first in 1953 for Editorial Writing and the second in 1984 for Commentary.

Royster died in 1996, and his personal papers are housed in the Southern Historical Collection at Wilson Library. In addition, Royster published several books over the course of his life — including My Own, My Country’s Time, A Pride of Prejudices, and Journey Through the Soviet Union — all of which can be found in UNC Libraries.

Sources & Additional Readings:

Collection of “Around the Well” columns

“Vermont C. Royster (1914-1996),” written by Will Schultz. North Carolina History Project. http://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/vermont-c-royster-1914-1996/.

Vermont Royster papers #4432, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Essential Royster: a Vermont Royster reader. edited by Edmund Fuller. Chapel Hill, N.C. : Algonquin Books, 1985.

My Own, My Country’s Time: a journalist’s journey. Vermont Royster. Chapel Hill, N.C. : Algonquin Books, 1983.

A Pride of Prejudices. Vermont Royster. Chapel Hill, N.C. : Algonquin Books, 1984.

Journey through the Soviet Union. Vermont Royster. New York, D. Jones [1962].