In 1966 the UNC men’s varsity Glee Club celebrated their 75th touring season with a month-long tour through Europe, including 21 performances in England, France, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark, West Germany, and East Germany. Director Joel Carter (1913-2000) and student members collected a variety of items during their trip, now available in a new addition to the records of the Department of Music in the University Archives.

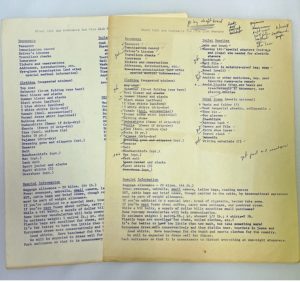

Dr. Carter’s planning materials include a packing list for club members. Suggested items include: a wool and summer blazer, a dressing gown and slippers, collapsible coat hangers, a shoeshine kit, and “your favorite tummy-ache remedy.” The list discourages liquids as “they are heavy and treacherous!”

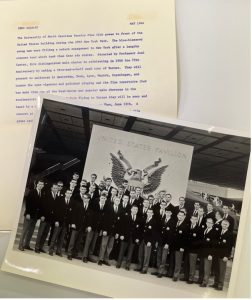

The first stop of the tour brought the club to New York City, where they performed a worship service at St. George’s Church in Greenwich Village followed by a national television performance on the Ed Sullivan show. Dr. Carter’s records include a draft letter by club members to Ed Sullivan requesting to perform on his show. The show, filmed on June 12, 1966, also featured The Dave Clark Five, tap dancer Peter Gennaro, and writer Elwyn Ambrose who recited poetry with a cat puppet.

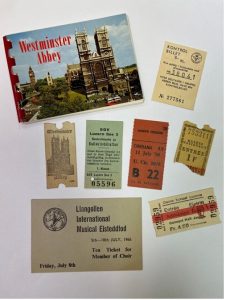

Paul Wyche, club president and class of 1967, saved his KLM and Eastern airlines boarding passes. These paper tickets have hand-written and stamped flight information and seat numbers. Two have passport control tickets attached. There are also ferry, bus, and train tickets. Someone collected travel brochures, including foreign currency guides, ferry boat brochures, and a tourist magazine from Copenhagen.

The Glee Club’s choice of songs, demonstrated in their partial repertoire list, emphasizes American music and composers. The list features two songs by Stephen Foster (1826-1864), sometimes called “the father of American music.” Further underscoring their ‘Americanness,’ they performed at Rebild National Park Society’s American Independence Day celebration, one of the largest Fourth of July celebrations outside of the United States.

The European tour event program describes an 1895 Glee Club poster calling their performances “rollicking songs, jigs and banjo picking.” The program goes on to say “[t]he banjos and jigs have been packed away with the knickers and knee socks worn by the Club’s earlier members. But the University of North Carolina Men’s Glee Club is still known for its ‘jolly programs’ and ‘rollicking songs.’” They paid homage to their early banjo pickin’ days with the song “Ring de Banjo” by Stephen Foster.

The club’s oeuvre included African American spirituals; however, many of the African American spirituals performed, with a notable exception of the arrangement of “Were You There?” by Henry Thacker “Harry” Burleigh (1866-1949), were arranged by white composers. The club also performed exclusionary and injurious music, the most conspicuous example being “Dixie,” the unofficial anthem of the Confederacy, which they sang on the Ed Sullivan Show.

The club members found time to sightsee in between performances. Tourist memorabilia is scattered throughout the collection, including museum and Cinerama tickets. Someone saved a hotel shower cap, receipts, and blank postcards. A hastily scrawled note to a member who slept in tells him where to meet the group later that morning.

In a 1986 Chapel Hill Newspaper article on the Glee Club reunion, Betty North described their experiences in Paris:

By the time the group arrived in Paris, one of the last major stops, the club members were tired and running short of money, North said. The group stayed in a cheap hotel and toured the city in the least expensive way possible: by foot and by subway. “In the winter, the hotel we were staying in was a house for ladies of the night, and the desk clerk was a madame,” North said. “She just couldn’t understand why all these young men were staying there, next to the Moulin Rouge, and not going after the women.”

The members still had plenty of indecorous fun. Two German beer coasters and a ticket for a casino in Lucerne are in the collection. There is also a Playboy Club napkin of unknown American origin—likely from St. Louis or New York City during the national tour.

The club’s travel to Leipzig and East Berlin in East Germany, then under Soviet rule, served as a subdued note. A four-page information pamphlet from the United States Mission in West Berlin details the process of traveling into East Berlin. The group shared a general anti-Soviet sentiment in a 1966 newspaper article, describing the land as “creepy,” “completely colorless,” and “dirty, barren and downright spooky.” The article also describes East Germans as glaring at the diesel bus. Student photographer Jock Lauterer photographed the group in East Germany; the negatives of these photos are in the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives in Wilson Library.

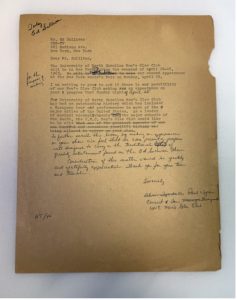

Despite their fundraising efforts, the club ran out of money by the end of the tour. In a letter to the Alumni Annual Giving fund dated September 22, 1966, Dr. Carter asked for a gift to help cover their $3,025.49 deficit. Dr. Carter mentions he enclosed “pictures, news releases, brochures, and other souvenirs of our European Tour.” Perhaps Dr. Carter and members collected memorabilia to give as thank you gifts to their tour sponsors, and this small collection was left.

Sources:

Liz Lucas, “Glee Club Recall ’66 Tour,” The Chapel Hill Newspaper, May 11 1986.

Joan Page, “Glee Club’s Visit in Red Area Brings Somber Note to Travels,” Newspaper clipping, 1966.