This timeline presents key events in the history of Latinx students, faculty and staff, and programs at UNC-Chapel Hill. The timeline was developed using resources available in Wilson Special Collections Library. It is not intended to be comprehensive, but it is our hope that this will be a helpful resource for anyone interested in learning more about Latinx history at Carolina. We welcome any corrections or suggested additions at wilsonlibrary@unc.edu.

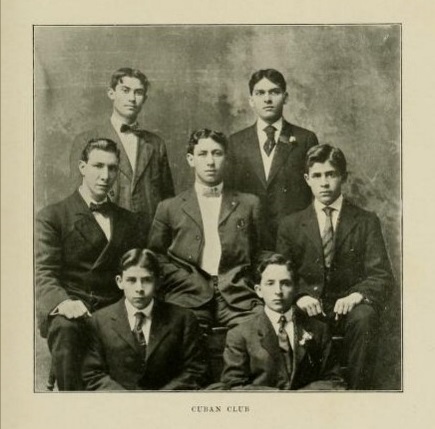

1908-1911

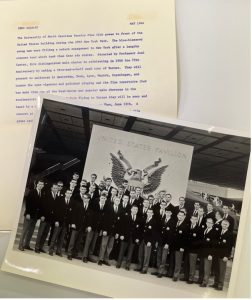

UNC sees an influx of students from Cuba. Members of the “Cuban Club” are pictured in the 1909 and 1910 Yackety Yacks. At one point the Cuban Club had 11 members, a significant population at a time when UNC had a total enrollment of 778 with only 55 out-of-state students.

Source: For the Record blog, 28 March, 2016. The Curious Case of the Cuban Club – For the Record (unc.edu)

1940

UNC establishes the Inter-American Institute, the university’s first formal structure for curricular and program development in Latin American studies. Following its establishment, UNC begins offering courses in Latin American history and geography.

Source: Elizabeth Hasseler, “A Century of Latin American Studies at Carolina.” Carolina Passport, 2020. A Century of Latin American Studies at Carolina – UNC Global

January – March 1941

The Inter-American Institute organizes a six-week “winter summer school” for 110 visiting educators, journalists, and professionals from South America. Countries represented included Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Peru. The visitors participated in classes, lectures, and tours. In recognition of their visit, they created an endowment in the University Libraries for the purchase of books and materials about South America.

Sources: Elizabeth Hasseler, “A Century of Latin American Studies at Carolina.” Carolina Passport, 2020. A Century of Latin American Studies at Carolina – UNC Global; Daily Tar Heel, 25 January 1941, 2 March 1941

1949

The Inter-American Institute is reorganized and renamed the Institute of Latin American Studies.

Source: Elizabeth Hasseler, “A Century of Latin American Studies at Carolina.” Carolina Passport, 2020. A Century of Latin American Studies at Carolina – UNC Global

February – March, 1960

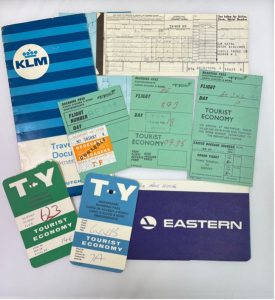

Fifteen students from Cuba visit UNC to take part in a four-week seminar focusing on sociology and anthropology. The visit is organized by the UNC Institute of Latin American Studies, the University of Havana, and the U.S. State Department.

Sources: Elizabeth Hasseler, “A Century of Latin American Studies at Carolina.” Carolina Passport, 2020. A Century of Latin American Studies at Carolina – UNC Global; Daily Tar Heel, 3 February 1960.

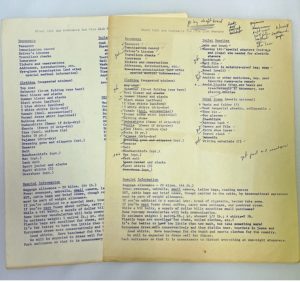

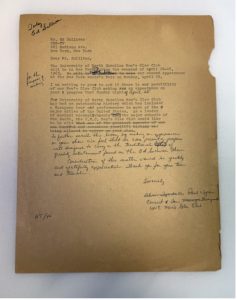

Collection Title: Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1937-1983 #40089 Collection Title: Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1937-1983

1969

The Annual Report of the Director of the Office of Records and Registration includes data for minority students enrolled at UNC, including students described as “Spanish American Surnamed.” For fall 1969, UNC reports 17 undergraduate and 21 graduate Latinx students. This data is drawn from information provided voluntarily by students on their fall semester matriculation cards.

Source: Office of the Registrar and Director of Institutional Research of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records (40130), University Archives.

1979

The Institute of Latin American Studies selects twelve Mexican scholars for advanced study and research at UNC, funded by Pepsi-Cola of Mexico. The following year, the Institute selected an additional six Venezuelan scholars. The program concluded in 1983.

Source: Mexican Visiting Scholars Program, Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40089, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

1986

There are 22 Latinx faculty members at UNC as of December 1986, according to the Office of Institutional Research. At the time, there are 1,975 faculty members at Carolina.

Source: Fact Book, 1986-87. UNC Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Fact Books | OIRA (unc.edu)

Fall 1990

The Carolina Hispanic Association (known as CHispA) is established by student Catherine Lindsay with a group of around ten students. As of Fall 1990, there are 201 Latinx students enrolled at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Source: Daily Tar Heel, 2 April 2001. The Daily Tar Heel. (Chapel Hill, N.C.) 1929-1943, April 02, 2001, Image 1 · North Carolina Newspapers (digitalnc.org); Fact Books from the UNC Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Fact Books | OIRA (unc.edu)

Fall 1999

Dr. María DeGuzmán, Eugene H. Falk Distinguished Professor of English & Comparative Literature, establishes the UNC Latina/o Cultures Speakers Series. The speaker series has brought prominent Latinx scholars, authors, and artists to campus for lectures and discussions.

Sources: “About the UNC Latina/o Cultures Speakers Series,” About The UNC Latina/o Cultures Speakers Series | UNC Latina/o Studies Program; “List of the scholars, writers, performers, and educators that the UNC Latina/o Cultures Speakers’ Series has brought to campus and/or supported with funding.”

30 October 1999

Undergraduate students Sussy Portillo and Dawn Anderson crossed into the Kappa Chapter of Latinas Promoviendo Comunidad/Lambda Pi Chi Sorority, Incorporated. This marked the extension of Duke University’s LPC/LPCSI Kappa Chapter to UNC’s campus as one of the first Latina-focused sororities to be represented at the University.

Source: Phi Chapter – Latinas Promoviendo Comunidad/Lambda Pi Chi Sorority, Inc.

Spring 2000

Dr. María DeGuzmán taught English 864: Studies in Latinx Literatures, Cultures, Criticism (including “LatinX Environmentalisms”), the first graduate-level course on Latinx-U.S literature(s), culture(s), and criticism at UNC.

Source: Interview with Dr. María DeGuzmán, 2017, in the Latina/o Studies Program of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40489, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

19 April 2001

The Alpha Iota Chapter of the La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Incorporated (LUL) was established on UNC’s campus. This is the one of the first Latino-centered fraternities to be represented at UNC.

Source: About Us: AI – UNC LUL

Fall 2002

Enrollment of Latinx students tops 500 for the first time. 511 students, identified as Hispanic in university data, make up 2.0% of the total student population.

Source: Fact Books from the UNC Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Fact Books | OIRA (unc.edu)

2003

UNC faculty members Paul Cuadros and Peter Kaufman establish the Scholars’ Latino Initiative (SLI), a scholarship and mentoring program housed in the UNC Center for Global Initiatives.

Source: About Us – Scholars Latino Initiative, About Us | LatinxEd

2004

Building on the success of the Latino/a Cultures Speaker Series, Dr. María DeGuzmán and other faculty propose a new undergraduate minor in Latino/a Studies. The minor is approved in March 2004, leading to the establishment of a Latino/a Studies Program. The new minor and program are inaugurated with a celebration in Dey Hall on September 20, 2004.

Sources: “History of the UNC Latina/o Studies Program,” History of The UNC Latina/o Studies Program | UNC Latina/o Studies Program; Daily Tar Heel, 21 September 2004. The Daily Tar Heel. (Chapel Hill, N.C.) 1929-1943, September 21, 2004, Page 3, Image 3 · North Carolina Newspapers (digitalnc.org)

January 2006

The Daily Tar Heel publishes “La Colina,” a Spanish-language supplement to the newspaper. The single-page supplement runs monthly through 2008 and includes original stories of interest to UNC students and the local Latinx community.

Source: Daily Tar Heel, 25 January 2006. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92068245/2006-01-25/ed-1/seq-1/

Fall 2007

Enrollment of Latinx students tops 1,000 for the first time. 1,010 students, identified as Hispanic in university data, make up 3.5% of the total student population.

Also in Fall 2007, the number of Latinx faculty at UNC passes 100 for the first time. Of these, more than half (54) are in fixed-term positions. Latinx faculty make up 3.4% of the total faculty at UNC.

Source: Fact Books from the UNC Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Fact Books | OIRA (unc.edu)

November 2007

“Los Sueños de Angélica,” a film by UNC alumnus Rodrigo Dorfman, is screened at the FedEx Global Education Center. The film, the story of a Latinx couple in Durham struggling to decide whether to stay in the United States, is, according to the Daily Tar Heel, the “first Latino feature film to come out of North Carolina.”

Source: Daily Tar Heel, 14 November 2007. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92068245/2007-11-14/ed-1/seq-3/

10 April 2010

The Carolina Latina/o Collaborative (CLC), a university-backed collective focusing on Latina/o campus and community-wide affairs with plans to create a dedicated Center, is launched in Craige-North Residence Hall.

Source: Press Release, in the Latina/o Studies Program of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40489, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

24 April 2010

After the National Executive Board (NEB) of Latinas Promoviendo Comunidad/Lambda Pi Chi Sorority, Inc. decided to grant UNC recognition of its own chapter, students Christina Jusino and Wendy Tapia cross into LPC/LPSCI and mark the founding of LPC/LPSCI’s Phi Chapter.

Source: Phi Chapter – Latinas Promoviendo Comunidad/Lambda Pi Chi Sorority, Inc.

Fall 2010

Latinx enrollment continues to grow. University sources report 2,428 students described as “Hispanic of any race,” representing 8.3% of the total student population.

Source: Fact Books from the UNC Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Fact Books | OIRA (unc.edu)

23 April 2011

The Beta Lambda Chapter of Omega Phi Beta Sorority, Incorporated is established on UNC’s campus.

Source: Omega Phi Beta Sorority, Incorporated – Heel Life

April 2016

The UNC Centers and Institutes Review Committee approves the proposal to create a Latinx Center on campus. The Center receives final approval from the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees in January 2019.

Source: Latinx Center website: Our History – Carolina Latinx Center (unc.edu)

2017

The Office of the Executive Vice Provost formed the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) and Undocumented Resource Team, an effort to coordinate resources and information for undocumented students at Carolina.

Source: DACA/Undocumented Students – Dean of Students

2018

UndocuCarolina is established as part of a collaborative effort to support education and programming around contemporary immigration policy and a better understanding of issues faced by undocumented students and families. UndocuCarolina also offers Ally Trainings, half-day workshops focused on immigration, education policy, and best practices for providing support to undocumented students.

Source: UndocuCarolina (unc.edu)

Spring 2018

The Carolina Hispanic Association (CHispA) is renamed Mi Pueblo to reflect the group’s vision of unity and inclusivity.

October 2018

Ricky Hurtado and Elaine Townsend Utin establish LatinxEd, a nonprofit educational initative providing support to Latinx students and immigrant families.

Source: LatinxEd website.

4 October 2019

The UNC Carolina Latinx Center opens in Abernathy Hall.

Source: Latinx Center website: Our History – Carolina Latinx Center (unc.edu)

January 2020

UNC faculty member Todd Ramón Ochoa chairs the UNC DACA and Undocumented Resource Team.

Source: Daily Tar Heel, 12 January 2020. Universities are preparing for the future of dreamers amid DACA’s potential rollback – The Daily Tar Heel

Fall 2020

UNC employs 201 faculty members identified as “Hispanic of any race.” These faculty make up 4.9% of the total faculty at Carolina.

Source: Fact Book, 1995-96. UNC Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. fb2007_2008.pdf (unc.edu)

November 2020

UNC alumnus and staff member Ricky Hurtado is elected to the North Carolina House of Representatives, becoming the first Latinx Democrat elected to the state legislature.

Source: INDY Week, 4 November 2020. Ricky Hurtado Becomes the First Latino Democrat Candidate Elected to North Carolina State House – INDY Week

Fall 2022

For the Fall 2022 semester, 9.3% percent (2,961) of UNC students are identified as Hispanic.

Source: UNC Office of Institutional Research & Assessment. Student Characteristics, Fall 2022. Analytic Reports | OIRA (unc.edu)