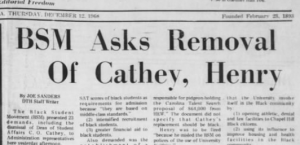

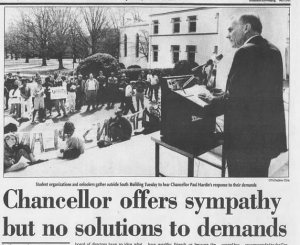

The Confederate Monument on the UNC-Chapel Hill campus has been the subject of controversy and protest for decades. A detailed timeline and corresponding archival materials related to the monument between 1908 and 2015 can be explored online via our Guide to Resources about UNC’s Confederate Monument. While some aspects of the current protests mirror past efforts, social media has facilitated new approaches for sharing information and sparking action on campus. In an effort to document the current protests, we knew it would be important to explore methods for collecting a sampling of tweets related to the Silence Sam protests.

We decided to use a tool called twarc to harvest tweet data for specific hashtags searches. Twarc is a Python package that makes use of the Twitter API to collect tweets. Between August 22 and December 15, 2017, we performed a weekly search and harvest of #silencesam and #silentsam. In addition, we infrequently captured select complementary hashtags: #boycottunc #boycottunctownhall #iaarchat and the @Move_Silent_Sam user account. 15,063 tweets were collected across all searches. The hashtags #silentsam and #silencesam make the up the majority with 12,993 tweets collected.

The tweets are in a raw form, so to speak. Twarc returns the tweets and associated metadata in a JSON document. So, in this collection you won’t automatically find a timeline that looks like the Twitter website. Instead, what we have is a structured text document with many lines and each line represents a tweet and associated metadata about that tweet. The data can be manipulated in a variety of ways for analysis or viewing. A wide variety of visualization tools could be useful for working with the data.

To get started working with this collection, though, you’ll first need a Twitter account and Hydrator or twarc installed.

The first step is to “hydrate” the dataset. There are some specific access stipulations for this collection due to the Twitter API terms of service. We cannot make the full data we collected available for use. In particular, we are unable to make deleted tweets available for use. Instead, we provide a list of the tweet identifiers (tweet ids) for all the tweets we’ve collected in our repository. This list of identifiers can be hydrated by querying the Twitter API for the tweets that are still publicly available. There are two options for hydrating the tweet ids.

Download the Hydrator tool

- You’ll need to authorize the app to connect to your Twitter account.

- Upload the tweet identifier document to Hydrator and start the process.

- Download the hydrated tweets from the tool.

Hydrate using the command line with twarc

- This method will require you to have Twitter API credentials. It’s not as intense as it sounds. Social Feed Manager, a project at George Washington University Libraries, provides a helpful guide in their documentation under the Adding Twitter Credentials section. Don’t worry about the parts that are specific to using Social Feed Manager. Your API keys will be entered via command line when setting up twarc. Instructions for setting up twarc are available on GitHub.

Once you have hydrated the dataset using one of the options above, you’ll have the full text of tweets and metadata in a JSON document or a CSV spreadsheet (from Hydrator).

The next step is to begin working with the data. You could use a variety of tools to visualize the data. Twarc comes with a few useful “utilities” that can also be used. A few are highlighted below:

wordcloud.py

emoji.py

wall.py

The wall.py program is the best way to generate a timeline of tweets that can be read one by one.

noretweets.py and deduplicate.py

These programs may be useful if you want to pare down the dataset. We don’t anticipate much duplication of tweets in the dataset, but no deduplication has been performed by us prior to making the collection available.

A note on images and video: There are limitations to collecting video and image files embedded in tweets due to the nature of the collecting by API. You may try using the method shared in this blog post from Tim Sherratt under Get Images. He uses image URLs and wget to gather pictures.

Access the Collection: You can find the collection description here and access to the tweet identifiers documents can be found here.

Other on-going collecting efforts related to the Confederate Monument protests that began on August 22, 2017 can be found:

- UNC-Chapel Hill Ephemera Collection (40446)

- UNC Libraries’ Web Archives, Confederate Monument Protests related websites.

If you have materials related to the protests – like photos, signs, or video – and you are interested in donating these materials to the University Archives, please contact us by email archives@unc.edu.

Other twarc and social media archive resources:

- Digital Humanities/Digital Scholarship resources

- Documenting the Now website and blog.

- Social Feed Manager website.