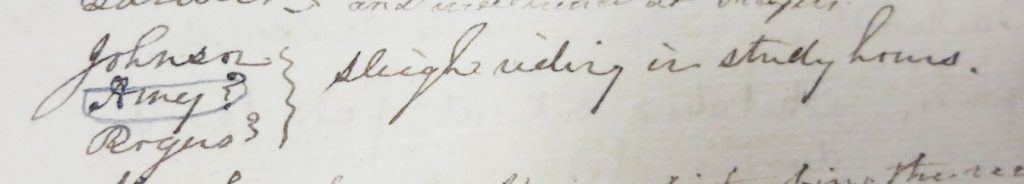

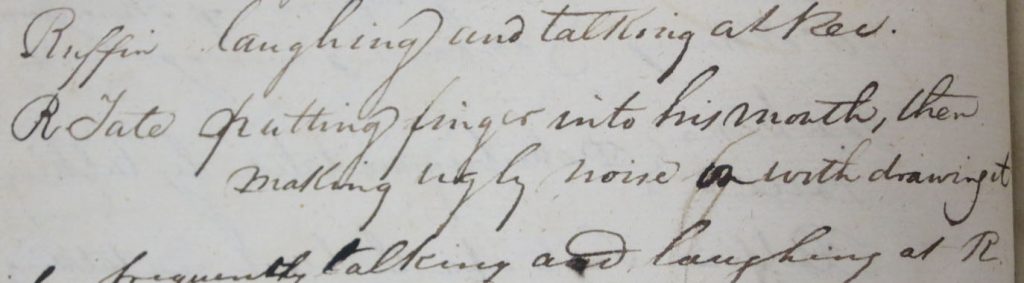

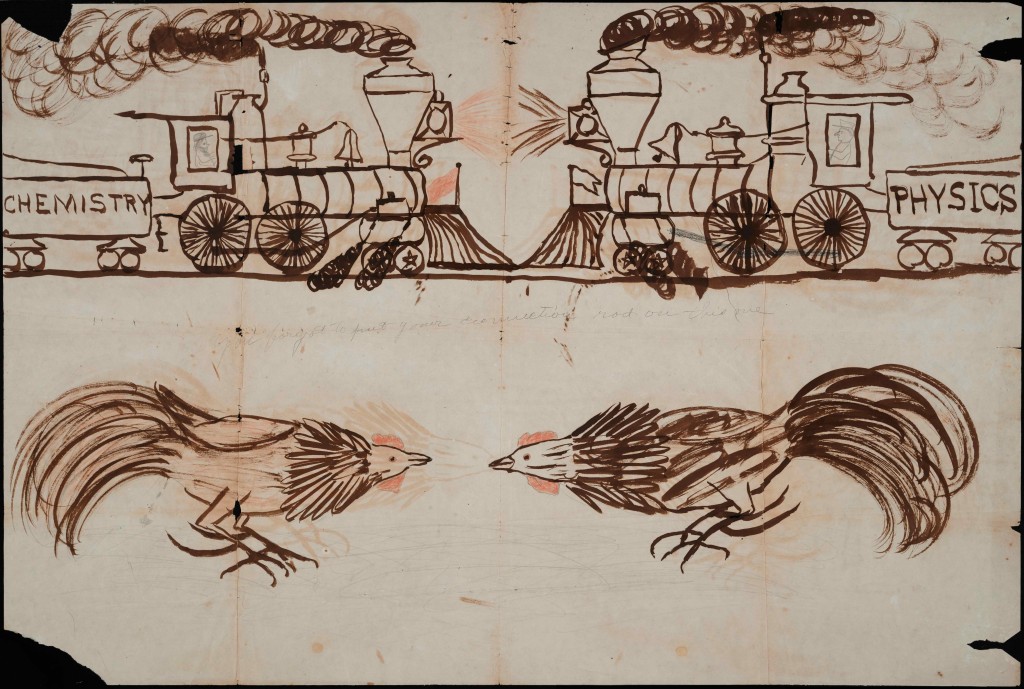

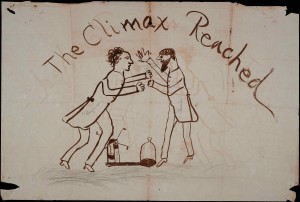

A late 1870s conflict between the Chemistry and Physics departments depicted as a train wreck and a cock fight. From the University of North Carolina Papers (#40005), University Archives.

A few years ago, we posted about a series of cartoons found in the University of North Carolina Papers (#40005). The large, undated drawings showed Chemistry and Physics as colliding trains, fighting roosters, and scuffling men. We weren’t sure when the cartoons were made, or what exactly they meant. But while searching the Daily Tar Heel on Newspapers.com today, I stumbled across a story that offers an explanation – a story of inter-departmental conflict and a creative student prank.

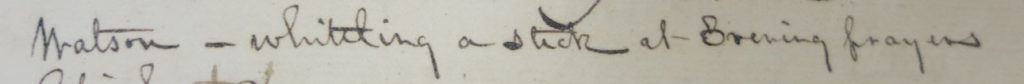

The June 6, 1904 issue of the Daily Tar Heel reports that the Alumni Association invited Judge Francis D. Winston, class of 1879, to speak and share his memories of his time at UNC. In his speech, he recalled:

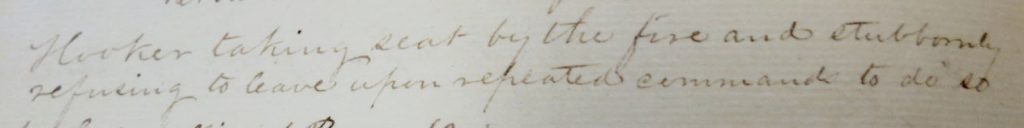

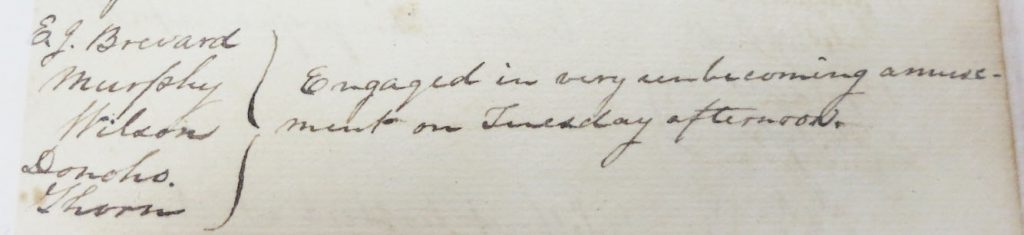

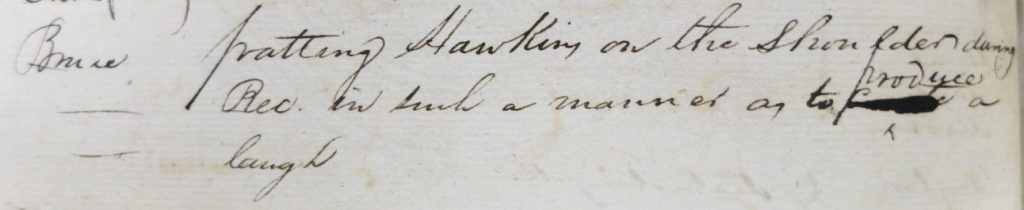

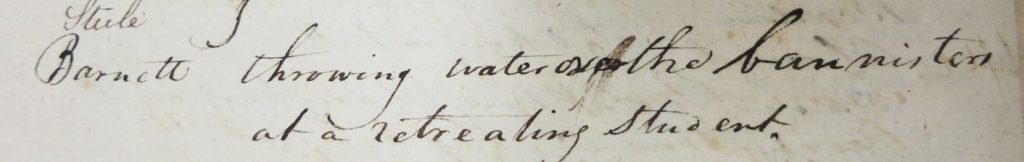

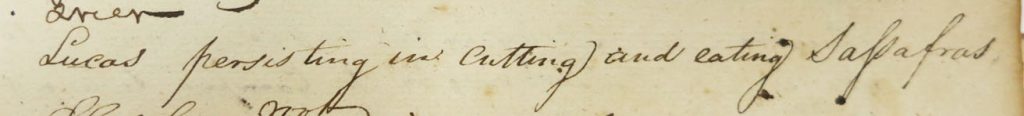

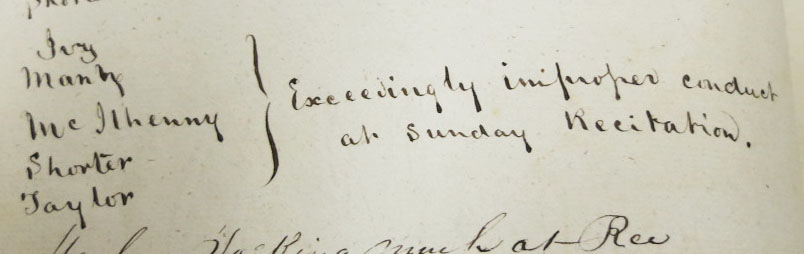

The reopened University* found itself practically without scientific apparatus. Its scarcity caused a conflict between two members of the faculty. The institution owned a dilapidated air pump, which was claimed by two departments – Chemistry and Physics. The professor of Physics, a man of few words and quick to act, took it to his room in the end of the Old West. In his absence the professor of chemistry had it taken to Person Hall by the college servant. Professor [Ralph Henry] Graves arrived on the scene just as it reached the door. He seized it and had it returned. Professor [Alexander Fletcher Redd] Reed [sic] interfered and they came ‘mighty nigh fighting’with chemistry worsted. And this was in the days of a struggling college, over an instrument which Dr. Elisha Mitchell had condemned as useless in 1856 and which had not exhausted air in a quarter of a century.

Two men, presumably Professors Redd and Graves, shown in conflict over an air pump. The man labelled “Chemistry” has a speech bubble that reads, “I’ll be damned if you shall.” From the University of North Carolina Papers (#40005), University Archives.

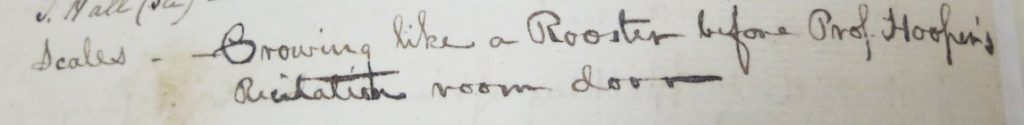

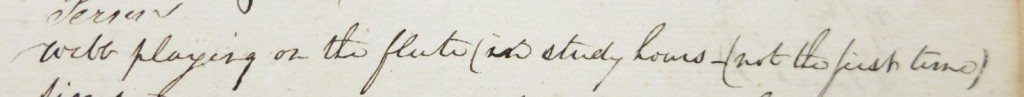

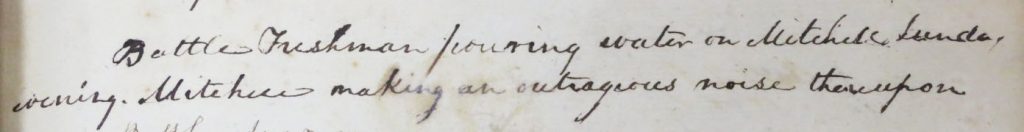

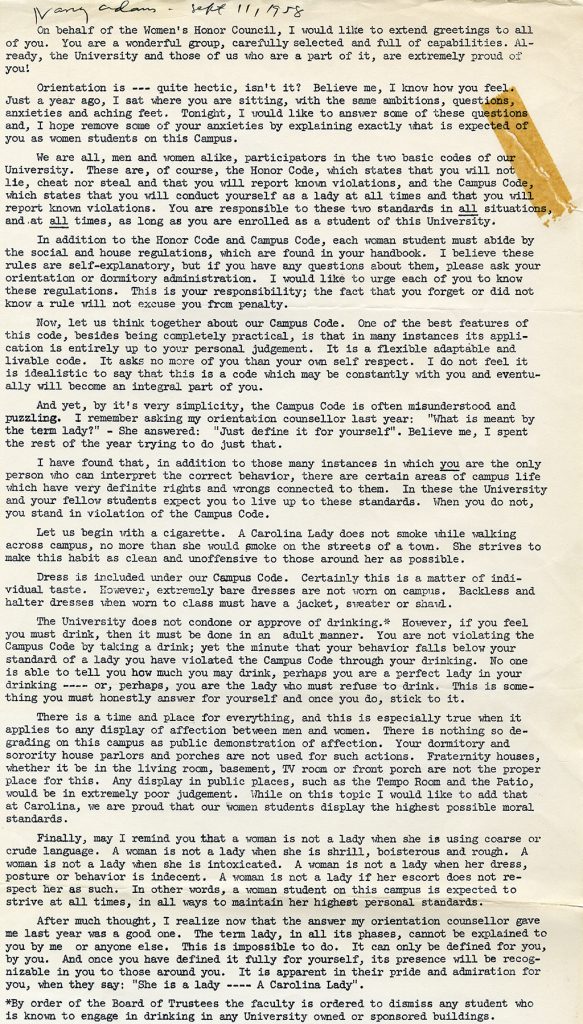

The morning after this occurrence there was seen over the rostrum in the chapel, a large drawing in flaming colors, of two engines approaching each other on the same track. They were labeled Chemistry and Physics. Another scene told the story. Chemistry was derailed and demolished. Every student was at prayers that morning. The interest was manifest.

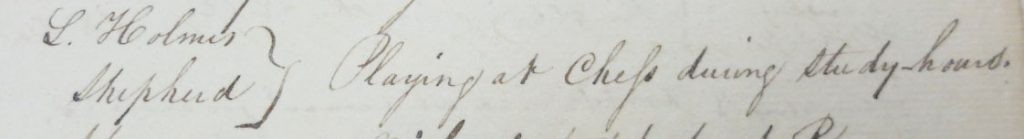

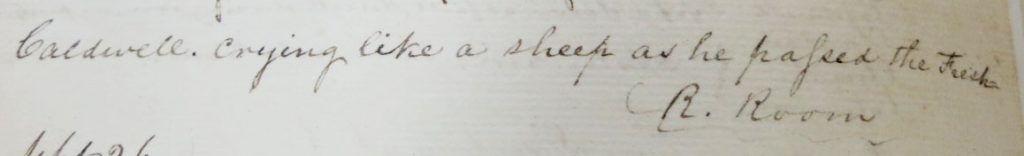

Dr. [Charles] Phillips was conducting chapel prayers that week. When he entered the door he took in the situation at a glance. When near the bull pen he broke into a quick run. He was applauded. He rushed up the steps to the hanging cartoons, but he failed to reach them, and he tried again and again. He was not without sympathy in the student body. How well do I recall their efforts of help and encouragement, when with his hand within an inch of the paper some one would cry: “Just a little more, oop-a-doop, a little higher.” But it was beyond his reach and he sat down. Wilson Caldwell, the college servant was sent for and the papers removed and prayers were said.

The next morning the artist put the incident into another form by having a game cock labeled Physics after a crestfallen, retreating rooster named Chemistry. The crowd was expectant. The good doctor saw the cartoons as he entered the door. He went to the desk with measured step. He appeared not to notice it. In the lesson that he read occurred this verse: ‘Watch ye therefore, for ye know not when the master of the house cometh, at even or at midnight,’ and here he paused, ‘or at the cock crowing in the morning, lest coming suddenly he might find you sleeping.’

Though Winston’s memories of the cartoons and the event they commemorated – shared thirty years after the fact – may not be entirely reliable, these cartoons now make a lot more sense. We now know that they were created between 1875 and 1879 and refer to a real conflict between two departments on campus. The drawing of the two men fighting over a piece of equipment labelled “air pump” can be taken much more literally than previously thought, as we now know it depicts an actual dispute over an air pump.

Although Winston remembered the train and rooster drawings appearing separately and they are here presented on one sheet of paper, the holes and tears at the corners of these cartoons suggest that these may some of the original drawings he remembered being hung in Gerrard Hall during chapel exercises.

*The University of North Carolina was closed from February 1871 to September 1875. Learn more about the University during the Civil War and Reconstruction.