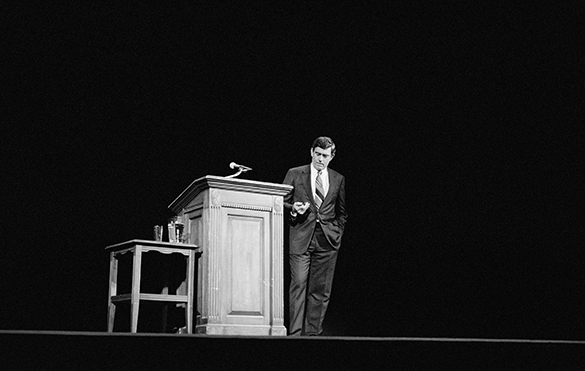

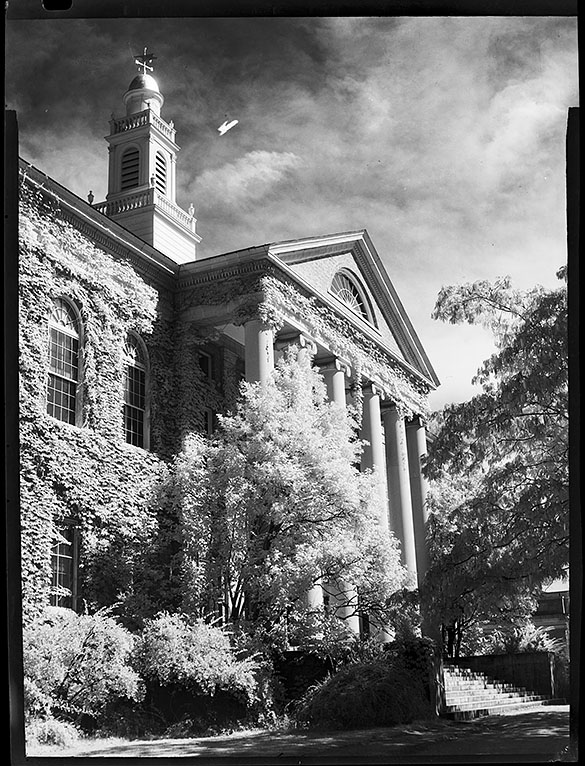

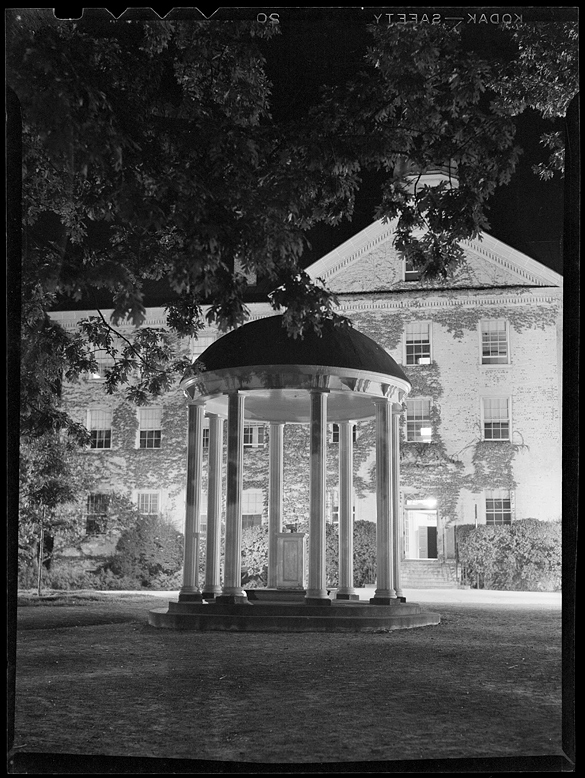

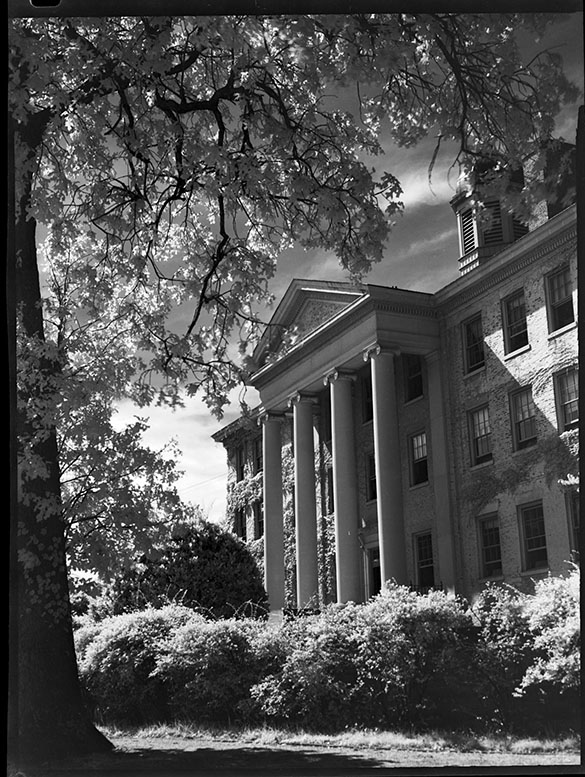

With the title caption “A New ‘Shot’ of the Old Well and South Building” in the October 1946 issue of The Alumni Review, this is Hugh Morton’s first UNC scene published in that magazine after WWII—with the columns vertically straightened, its edges cropped on all sides for publication, and accompanied by a long caption about Morton war service. This scan shows the entire negative. This was also on the magazine cover of The State for its October 5th issue, cropped even more tightly at the base of the well to accommodate the magazine’s masthead.

A View to Hugh has been on a summer vacation of sorts as other projects have pressed to the fore. This week marks the start of another school year at UNC, and the resumption of more frequent posts. Today, Hugh Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back 68 years to another time that many believe was “the best of times” at UNC.

But first . . . some background on the photographs used for this post. Above is Morton’s first post World War II photograph of a UNC scene published in The Alumni Review. Along with a long caption about Morton’s war service, the image filled an entire page inside the October 1946 issue. The November issue featured the photograph below on its cover, and its caption states that Morton had recently “presented to the Alumni Office a half dozen new pictures of familiar campus scenes.” Those photographs, most of which are not in the online Morton collection, illustrate this blog post. (If you are counting, however, you’ll come up with seven after the one above.)

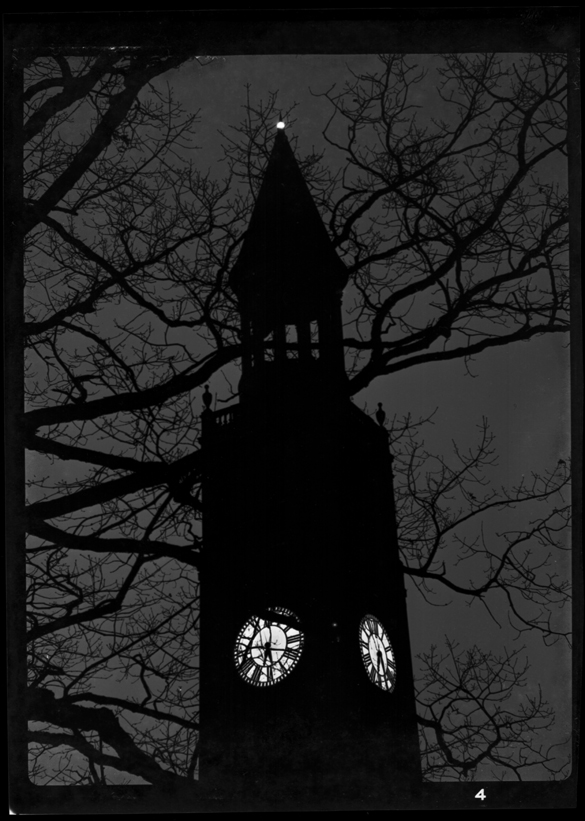

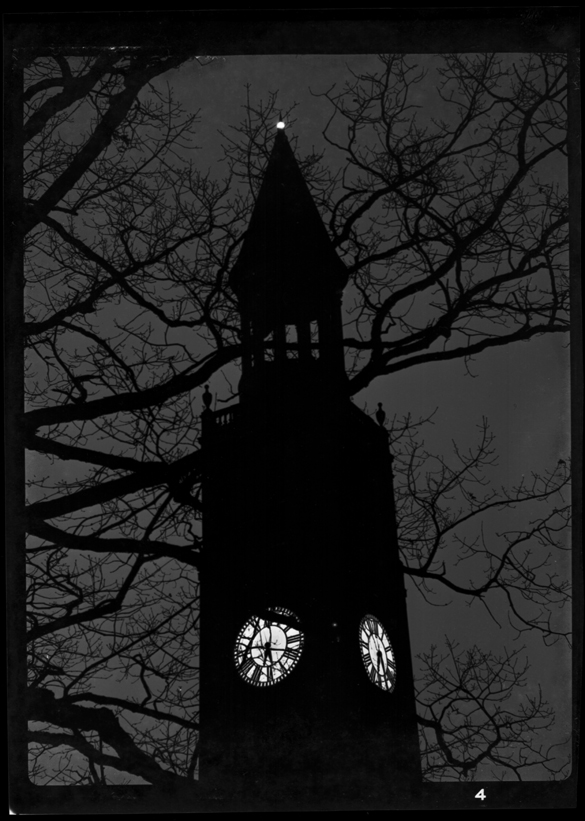

The November 1946 issue of The Alumni Review featured on its cover a cropped version of this photograph of the Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower.

It was a heterogeneous group of different ages and experiences—all due to a terrible war which had interrupted or affected the lives of most of us. . . We developed a tremendous school spirit in a very short time, and we were pretty charged up about changing the world and making it better.

—Class of 1947 “Revised Yackety Yack” 25th Reunion Edition, May 1972 by Sibyl Goerch Powe

Most UNC alumni consider their time in Chapel Hill as the best. I grew up in North Carolina during the late 1940s and early ‘50s and I remember that period as being the best. Many at Carolina, however, describe the years between VJ-Day (“Victory over Japan Day” celebrated on 2 September 1945 in the United States) and the Korean War—the years 1945 through 1950—as UNC’s “Golden Era.” World War II was finally over and Tar Heels everywhere could look ahead to the better times.

This era was born near the end of WWII when, on June 22, 1944, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944—forever to be known as the “GI Bill.” Among its many provisions, Title II Chapter IV revolutionized education in the United States, especially for those returning from service during World War II, because it empowered the federal government to reimburse colleges and other approved educational institutions for “the customary cost of tuition, and such laboratory, library, health, infirmary, and other similar fees as are customarily charged, and may pay for books, supplies, equipment, and other necessary expenses” of qualifying veterans—not to exceed $500 for “an ordinary school year.” The bill also allotted subsistence provisions of $50 per month for single veterans and $75 per month for those with dependents.

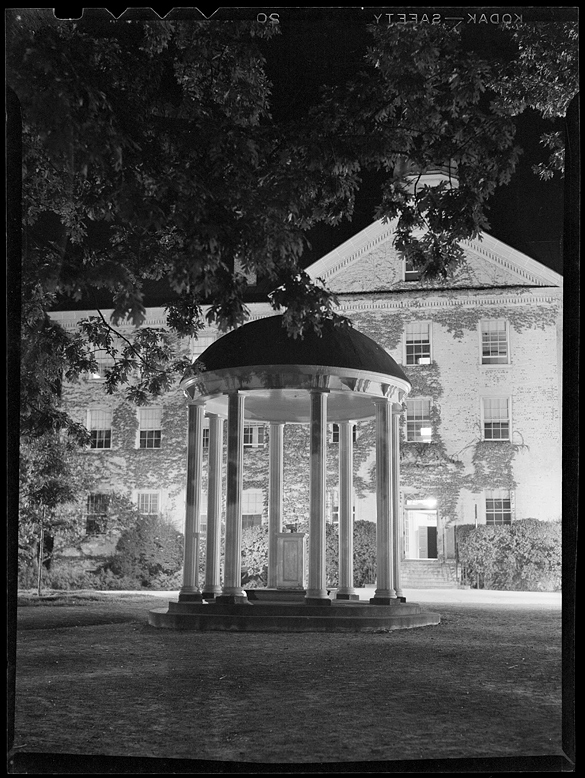

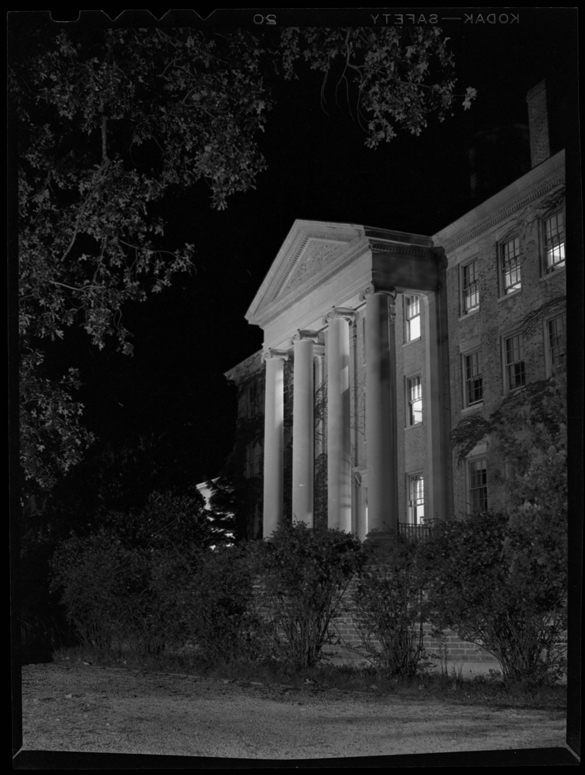

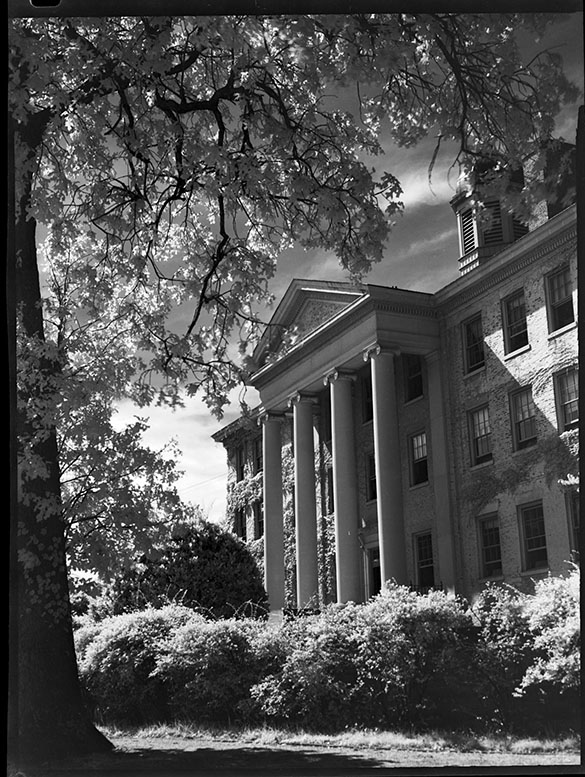

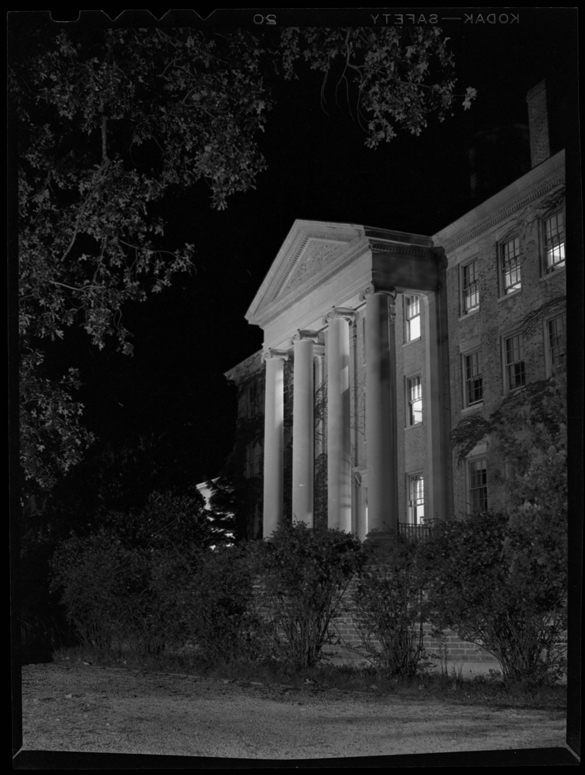

This night photograph of South Building appeared in the November 1946 issue of The Alumni Review with the caption title “Columns of South.” The caption writer described this photograph as being “symbolic of the University–old and new” showing “the ‘new’ side, looking south toward the area of greatest physical expansion of the campus in the years since the building period of the ‘Twenties.”

In the seven years following enactment of the GI Bill, approximately 8 million veterans received educational benefits, and of that number about 2.3 million attended colleges and universities. Enrollment at UNC rose to 6,800 which was 2,400 more than any time before.

As one would imagine, this jump in enrollment caused some housing and classroom-size challenges. An interesting article in October 1945 issue of The Alumni Review discussed the anticipated effects of armistice on UNC’s student housing. “The exodus of the U. S. Navy Pre-Flight School on October 15 left the University with a surplus of dormitory space for men students for the first time since Pearl Harbor,” the magazine wrote. “A particular need that developed with the influx of veterans was accommodations for married students.” The article also noted that Lenoir Dining Hall, which had been reserved for the cadets, could now become “an All-University cafeteria.”

The December 1946 issue of The Alumni Review used this photograph of Manning Hall with a caption that explained the conditions on campus. “Like many other University buildings now, Manning Hall (home of the University’s Law School) is crowded with students. Enrollment in the school is now 217, a sharp rise from the student body of 13 to which the school dropped during the war.”

Quonset huts, trailers and pre-fabs became a way of life, despite the departure of pre-flight school cadets who had occupied ten dormitories. On south campus, the federal government constructed Victory Village in less than a year on 65-acres at a cost $1.25 million. Many of the returning vets who were married lived there. The Victory Village address book reads like a who’s who at UNC. Terry Sanford, William Friday, and William Aycock, along with 349 other families made up the extended neighborhood, which lasted until 1972 when it was torn down to make room for expansion of UNC Hospitals.

For others on campus, cots were set up in the Tin Can and under the seats at Emerson Stadium while many other students lived with Chapel Hill families. The returning veterans along with a normal compliment of high school students presented a conflict of personalities on campus. Never before had so many students had so little in common—and got along so smoothly together. Students held dances on special weekends along with fraternity parties and gatherings at the Student Union, which at that time was Graham Memorial. The Big Band Era was still around although winding down and Tommy Dorsey made a return to campus. He had been a guest, along with Frank Sinatra, in May 1941 prior to our country’s entry into the war.

This negative is almost identical to the one used for the January 1947 cover of The Alumni Review. The only difference is the hands on the clock, which stand at 6:30. Morton made the negative used for the cover at 6:20. The latter negative survives, but it suffers from severe acetate negative deterioration. Morton use two different film types; this is a film pack negative. Shown in its entirety here, the cover image cropped the bit of light at the spire’s top and the lower portion of the clock and portions of both sides. The light at the top of the tower appears in both negatives, but it is blackened on the magazine’s cover.

The common denominator for all on campus, however, was sports. Leading the Carolina Spirit was Head Cheerleader Norman Sper, Jr. Leading the Carolina Band was Professor Earl Slocum with featured bandsman Andy Griffith. And the man on the sideline and court-side with the camera was Hugh Morton. It was during this post-war period that Morton’s photography blossomed. Interestingly, Morton did not return to Chapel Hill to finish his final year of college despite the GI Bill. Instead, he entered his grandfather’s real estate business, Hugh McRae & Co., in Wilmington—but a camera was always close at hand.

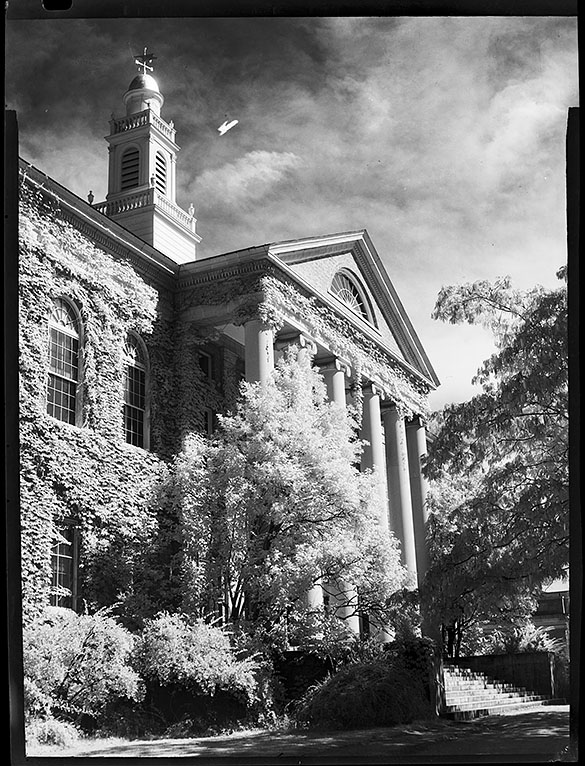

This scan shows the full negative of the scene used by The Alumni Review for its March 1947 cover. Given the vertical format of the magazine, however, they cropped off the right side of the image. The caption reads in part, “We are indebted again to Hugh Morton ’43 for this month’s cover. With the magic of the camera he has pictured Graham Memorial building (at left) and the trees which line the walk toward Old East Building in a romantic scene.”

Many years later, on May 13, 1989, as part of UNC’’s Graduation/Reunion Weekend, the General Alumni Association offered its annual presentation of “Saturday Morning in Chapel Hill.” The ’89 edition featured a panel discussion consisting of ten Tar Heel athletes from the Golden Era, led by Robert V. “Bob” Cox, UNC Class of ’49, and a Hugh Morton slide show. The title of the program was “Why Did We Have it So Good and What Made US Different?” It played to a near full-house in Memorial Hall on the UNC campus.

Wilson Library, now the home of the Hugh Morton collection, when it was known as the University Library. The Alumni Review cropped off the right side of this photograph to create a vertical for the cover of its April 1947 issue.

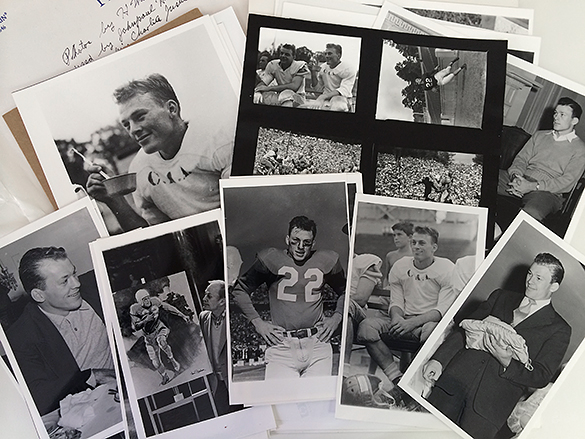

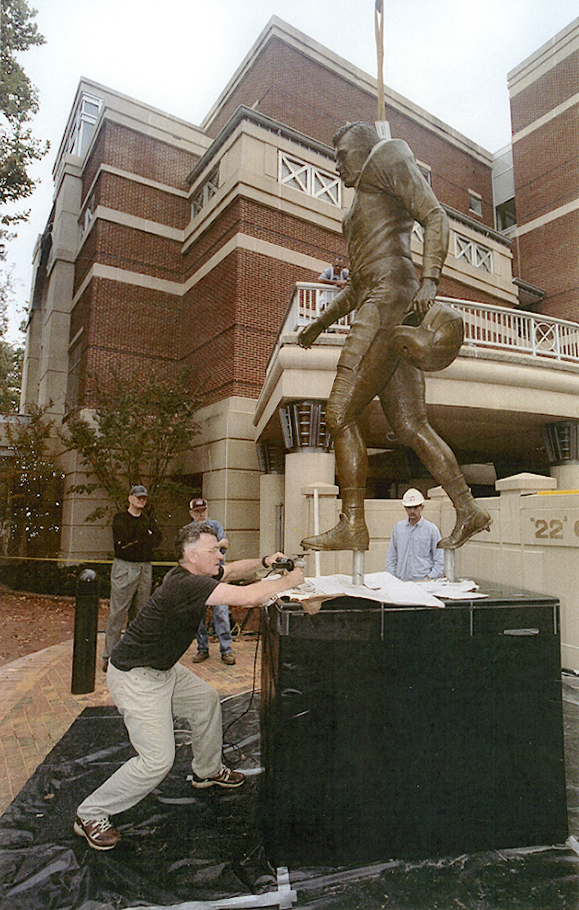

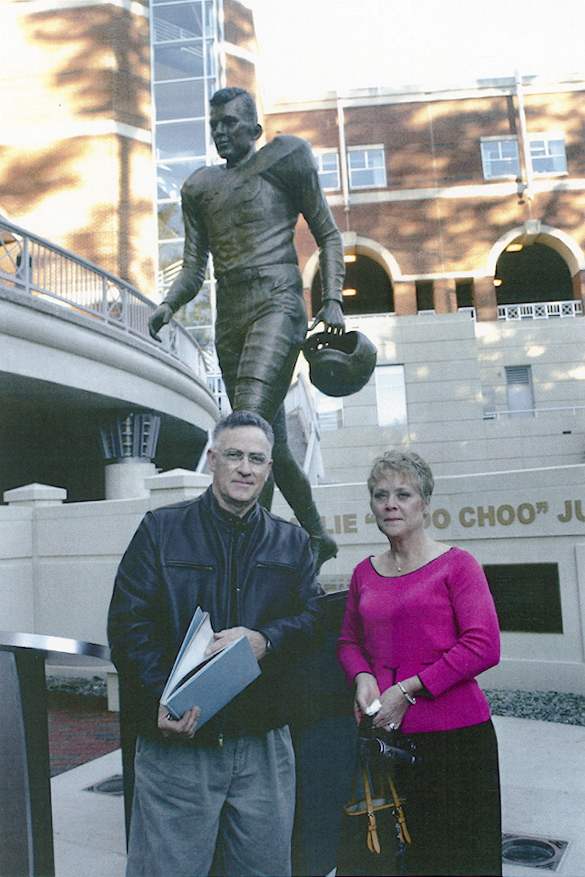

With coaches like Carl Snavely (football), Bunn Hearn (baseball), Tom Scott and Ben Carnevale (basketball), and Chuck Erickson (Golf)—all under the leadership of Athletics Director Robert Fetzer—Carolina won 32 Southern Conference Championships for the years 1945 through 1950 . . . plus 10 National Champions, 3 basketball and 3 football All Americas, 3 major bowls games and a football National Player of the Year. With names like Bones (McKinney), Hook (Dillon), Harvey (Ward), Vic (Seixas), Art (Weiner), Chunk (Simmons) and Sara (Wakefield). And of course the poster boy for the era was nicknamed “Choo Choo” (Charlie Justice).

Stellar athletes mingled with the regular student population along Franklin Street, just as they do today. However, the Franklin Street of 1946 was a lot different than the one the class of 2018 will come to know and love, One of those businesses from 1946 survives today at 138 East Franklin: it’s the Carolina Coffee Shop. Also back in ’46 there was Danziger’s with pizza on the menu, The Porthole “with rolls to die-for,” says Charly Mann on the web site “Chapel Hill Memories,” and Harry’s, with food, New York style. Also along Franklin was the Varsity Shop, Huggins Hardware, Foister’s Camera Store, and the Intimate Book Shop (the original one with the squeaky wooden floors). And you could go to the movies for $1.20 at the Carolina Theatre and see Hollywood’s top movie from 1946, The Best Years of Our Lives, from director William Wyler and starring Myrna Loy and Fredrick March.

This photograph of South Building appeared full-page in the April 1947 issue of The Alumni Review with a caption that noted that the building had been renovated in 1925. “Of the University’s 40,000 matriculates and ex-matriculates” it continued, “three-fourths of them knew this view of South Building in their student days.” The photograph as published is cropped significantly and rotated slightly clockwise to make the columns more vertical.

A Sidebar:

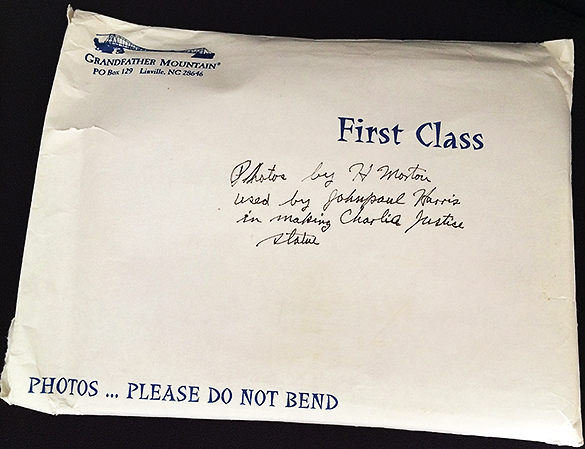

UNC’s great All America football player Charlie Justice was a Navy veteran and was eligible for the GI Bill. UNC also offered him a football scholarship. So Charlie asked UNC’s Athletics Director Robert Fetzer if his football scholarship could be transferred to his wife. Fetzer said he didn’t know but would check with the Southern Conference and the NCAA to make sure it would be OK. Turns out it was, and the Justices enrolled at UNC on February 14, 1946. Sarah Alice Justice became the first and possibly the only female to study at Carolina on a football scholarship.

UNC professor Stephen Davis will discuss the University in the 19th century, as discovered through two decades of archaeological exploration. Continue reading

UNC professor Stephen Davis will discuss the University in the 19th century, as discovered through two decades of archaeological exploration. Continue reading

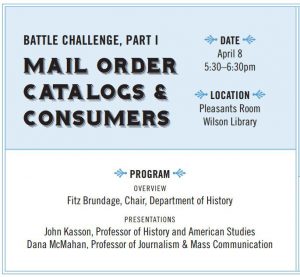

This Wednesday, Wilson Library and the UNC Department of History are putting on the first of two events that are 100 years in the making.

This Wednesday, Wilson Library and the UNC Department of History are putting on the first of two events that are 100 years in the making.![Kemp Plummer Battle [From the 1919 Yackety Yack, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library]](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/uarms/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2015/03/kpb-194x300.jpg)