This is the second essay composed for the Worth 1,000 Words project, written by independent scholar JANIS HOLDER. Holder is the former University Archivist for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She curated the 2007-2008 UNC Libraries exhibit A Nursery of Patriotism: the University at War, 1861-1945.

Hugh MacRae Morton, as a student at the University of North Carolina from 1939-1942, served as either official photographer or photograph editor for almost all of the major campus publications. He covered everything from basketball games and pep rallies to speeches and conferences for The Yackety-Yack, The Daily Tar Heel, Tar ‘n Feathers, and The Carolina Magazine; his assignments included work for the Alumni Review and the University News Bureau. Incredibly, he also found time to serve as photo-representative for the Winston-Salem Journal and sports photographer for both the Greensboro Daily News and Charlotte News. Evenings were spent developing pictures in his darkroom, leaving us to wonder exactly when he found time to attend classes and study, much less eat and sleep.

It was certainly a stimulating time to be a student at UNC. Morton’s freshman year, 1939-1940, was characterized by a growing concern with the war in Europe. There were many opportunities for intellectual debate and discussion about the pros and cons of U.S. involvement in the war. In May 1940, consolidated university President Frank Porter Graham offered the facilities of the entire university to the federal government for use in national defense preparations.

University faculty and administrators urged the students to stay in school and prepare themselves to be able to make optimum contributions both to the war effort and to post-war society. Many hoped the United States could be kept out of the war, but the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor dashed those hopes. In 1942, students began to leave the university in droves to enlist in various branches of the service and Hugh Morton, volunteering for the Signal Corps, was among them.

The first editorial published in the Daily Tar Heel after the attack on Pearl Harbor was dated December 9, 1941. The headline read “It’s Here – Let’s Face It,” and the editor encouraged students to “stay here and prepare … when the war is over, win or lose, boom or depression, there will be a tremendous shortage of trained, sensible leadership,” echoing university administrators. The students, however, reasoned that military training was part of their preparation for the future, and they voted to establish a military unit for all male students: the Carolina Volunteer Training Corps (CVTC). Four hundred students, organized into a battalion of four companies, began instruction by January of 1942.

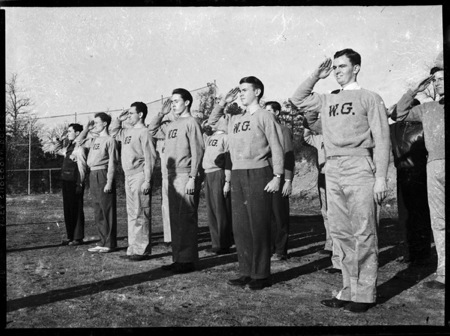

Though the CVTC received very little support in the way of supplies, uniforms, and equipment it was still a successful venture, and the first of its kind in the nation. This photograph was part of a series showing members of the CVTC during their drills. Note the variety in pants and shoes, and the proud expressions on their faces as they salute. The sweatshirts with the W. G. logo were ordinarily issued by Woollen Gym for physical education classes, but they were apparently the closest things to a uniform the CVTC could muster. With the advent of the Naval Aviation Pre-Flight Training School and growth of other military training programs, interest in the CVTC gradually diminished until its demise in the fall of 1943.

In addition to a focus on physical education and training, the university’s Committee on National Defense stressed the importance of meaningful discussions about the war and other current events. Student organizations took the lead in sponsoring thought-provoking events with well-known speakers.

This photograph was taken during the First Lady’s visit to the campus in January 1942, as the keynote speaker at a jointly-sponsored International Student Service-Carolina Political Union conference on “Youth’s Stake in War Aims and Peace Plans.” As President Graham and Eleanor Roosevelt stroll across campus, accompanied by student leaders Louis Harris, Ridley Whitaker, and Lucy Darvin, they are engaged in an animated discussion. Another photograph in this series shows Mrs. Roosevelt in a cafeteria line with Ridley Whitaker and Lucy Darvin.

This photograph was taken during the First Lady’s visit to the campus in January 1942, as the keynote speaker at a jointly-sponsored International Student Service-Carolina Political Union conference on “Youth’s Stake in War Aims and Peace Plans.” As President Graham and Eleanor Roosevelt stroll across campus, accompanied by student leaders Louis Harris, Ridley Whitaker, and Lucy Darvin, they are engaged in an animated discussion. Another photograph in this series shows Mrs. Roosevelt in a cafeteria line with Ridley Whitaker and Lucy Darvin.

Several years ago, Chancellor Emeritus William B. Aycock told me a story about “Dr. Frank.” Graham was an extremely busy man, and his mind was always preoccupied with lofty thoughts; he simply couldn’t be bothered to keep up with money, car keys, and other ordinary things. In fact, Aycock stated, Dr. Frank never had a driver’s license and was driven everywhere he needed to go. On one of Mrs. Roosevelt’s visits to the campus, Graham took her out to lunch, but when the time came to pay for their meal he searched his pockets and came up empty; Mrs. Roosevelt was obligated to pay for both lunches.

So perhaps this was a post-luncheon stroll, and their animated discussion was an apology from Dr. Frank for his forgetfulness at the cafeteria cash register, and assurance from Mrs. Roosevelt that she understood. I suppose we’ll never know.

In October 1941, with Naval cadets taking up dormitory space on campus and more soon to arrive, twenty-one university students were looking for a creative way to live better and more cheaply. Wartime budgets were strained; young men needed three square meals a day to thrive, but they were finding it difficult to afford the cafeteria food on campus. Led by Maury Kershaw and Dan Martin, the students came up with a solution – a co-op!

Fifteen of the boys moved into an eight-bedroom house at 120 Mallett Street; the other six took their meals at the house. The cost of this venture was five dollars a month per person for lodging, and five dollars a week per person for three full meals every day. Menus were carefully prepared ahead of time with regard to proper nutrition, and the budget occasionally allowed for such splurges as steak and fried chicken. Because they bought in bulk, local trades people offered the co-op a discount on its purchases.

Fifteen of the boys moved into an eight-bedroom house at 120 Mallett Street; the other six took their meals at the house. The cost of this venture was five dollars a month per person for lodging, and five dollars a week per person for three full meals every day. Menus were carefully prepared ahead of time with regard to proper nutrition, and the budget occasionally allowed for such splurges as steak and fried chicken. Because they bought in bulk, local trades people offered the co-op a discount on its purchases.

This photograph shows co-op manager and food buyer Dan Martin weighing produce at Pender’s grocery store. If you look closely, you can see the pressed-tin ceilings and chandeliers in the store, and huge piles of fresh vegetables and fruits. The posters on the wall and the hand-lettered sign advertising “Fresh Sliced Bread 5¢” are evocative of the era as well. This photograph was one of a series taken by Morton for a story in the March 1942 issue of Carolina Magazine. One of the published photographs shows an alternative shot of Dan Martin pulling boxes of Quaker Oats off the shelf, assisted by the store clerk. A sign beside the two men is perhaps even more evocative of the war era: “Temporarily Out of Sugar.”

The University of North Carolina was chosen as one of four locations for the United States Navy’s pre-flight training program in January 1942, and the campus rushed to prepare itself for the advent of the first group of trainees in May of that year. The front page of the February 28, 1942, Daily Tar Heel proclaimed: “AIR UNIT HERE: Knox Discloses 1,875 Cadets Will Train Here,” and succeeding issues in March detailed the difficulties of housing the influx of cadets. Though there was some dormitory space available, many students had to be moved as Alexander, Manly, Mangum, Grimes, and Ruffin dormitories were vacated for the Navy.

The March 25th issue of the Daily Tar Heel advised all “refugees” to register at the Campus Y: “All students who have found it necessary to move from the ‘fateful five’ dormitories due to the Navy invasion are asked to come by the office of the ‘Y’ and list their new addresses in the master directory.” No doubt there was some resentment due to the “Navy invasion,” but this was wartime after all, and sacrifices must be made.

Before it was formally decommissioned on October 15, 1945, the Pre-Flight School at UNC had trained 18,700 cadets, 360 Free French cadets, seventy-eight French officers, and 1,220 Navy V-5 officers. Two men who would later become United States presidents passed through: instructor Gerald R. Ford and cadet George H. W. Bush. One of Hugh Morton’s university friends, Orville Campbell, became the public relations officer for the Pre-Flight School, and called it “the greatest thing that happened to Chapel Hill since Davie founded it.”

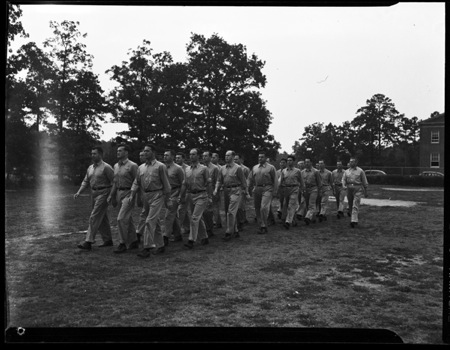

This photograph was part of a series taken for the May 24, 1942, Daily Tar Heel. Pictured are the Pre-Flight School officers drilling under Lt. Robert D. Robinson, in preparation for leading their own units. In many ways, this photograph represents the calm before the storm. Morton captured it while still a student “covering his beat,” prior to his joining the Army and being sent for his own military training.

REFERENCES

“Campus Organizations Issue,” Carolina Magazine, January 1942, p. 16, p. 24.

“First Lady to Keynote Post-War Planning Talks: Mrs. Roosevelt Accepts Bid to Lead Conference,” Daily Tar Heel, January 7, 1942, p. 1.

Komisaruk, Paul, “Adventure in Living: Cooperatives Are an Answer,” Carolina Magazine, March 1942, pp. 14-15.

A Nursery of Patriotism: the University at War, 1861-1945. Online exhibit accessed at http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/exhibits/patriotism/index.php

Excellent essay, Janis. Beautifully written with great historical information. I especially appreciated your listing references.