This essay was composed for the Worth 1,000 Words project by DAVE HANEY and LISA BALDWIN. Haney is the former Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education and Professor of English and Appalachian Studies at Appalachian State University (now Provost at Black Hills State University in South Dakota), as well as a musician and author on topics of philosophy, literature, and bluegrass music. Lisa Baldwin is a recent graduate of the MA program in Appalachian Studies at Appalachian State University, has taught elementary school for 30 years, is the founder of “Learning Through Song,” a music education program, and is a musician and songwriter who performs with Dave Haney and others.

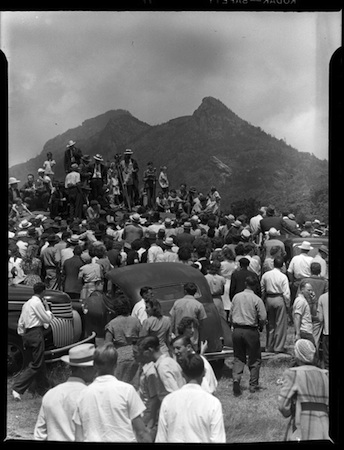

Although our  current understanding of traditional music festivals is shaped by the folk and bluegrass festivals that blossomed in the 1960s, both secular and religious traditional music had been performed in large outdoor settings in the Blue Ridge Mountains much earlier. Many of the largest of these events had inauspicious beginnings. On the secular side, the Annual Old Fiddler’s Convention in Galax, Virginia, according to the convention’s official web site, was started in 1935 by Moose Lodge #733 in order to raise funds and preserve regional musical traditions, and has since grown to one of the world’s largest fiddler’s conventions. Grandfather Mountain, in Linville, North Carolina, is the site of a similar phenomenon on the religious side. “The Singing on the Mountain” gospel convention has been held at the base of Grandfather Mountain on the fourth Sunday in June every year since 1925, when 150 people joined founder Joe L. Hartley for a family reunion of the Elbert Hartley and Nancy Cooke families. According to Hartley’s daughter Pearl, who was interviewed in Boone, North Carolina’s Mountain Times in 1992, “There were no lights, no telephones, no food stands” in the early years. “People sang, preached and ate all day. We use to sing from shape notes. . . . And they didn’t have anything but a guitar” (23).

current understanding of traditional music festivals is shaped by the folk and bluegrass festivals that blossomed in the 1960s, both secular and religious traditional music had been performed in large outdoor settings in the Blue Ridge Mountains much earlier. Many of the largest of these events had inauspicious beginnings. On the secular side, the Annual Old Fiddler’s Convention in Galax, Virginia, according to the convention’s official web site, was started in 1935 by Moose Lodge #733 in order to raise funds and preserve regional musical traditions, and has since grown to one of the world’s largest fiddler’s conventions. Grandfather Mountain, in Linville, North Carolina, is the site of a similar phenomenon on the religious side. “The Singing on the Mountain” gospel convention has been held at the base of Grandfather Mountain on the fourth Sunday in June every year since 1925, when 150 people joined founder Joe L. Hartley for a family reunion of the Elbert Hartley and Nancy Cooke families. According to Hartley’s daughter Pearl, who was interviewed in Boone, North Carolina’s Mountain Times in 1992, “There were no lights, no telephones, no food stands” in the early years. “People sang, preached and ate all day. We use to sing from shape notes. . . . And they didn’t have anything but a guitar” (23).

Hartley was “a farmer, a fire warden, and a philosopher,” according to Beverly Wolter’s obituary in the Winston-Salem Journal, written on the occasion of his death in 1966 at the age of 95. He married his third wife at the age of 82, having outlived his previous two wives, who had borne him 9 children. He was a passionate walker, as he recounts in his combined history of the convention and his walking experiences, and he actively promoted old-time preaching: pointing to the preaching stands at the convention, he told Wolter, “There’s where they do the real preaching. And some of those holy rollers really cut shines. And I can remember when those old black-bonneted women used to shout.”

Hugh Morton began photographing the convention in 1946, and he also “gave valuable assistance to the convention” that year, according to Hartley (11). At that time Hugh Morton was a major player in the Linville Company, which owned the mountain, and by 1952 Hugh would become the sole owner, so his documentation of and involvement with the convention was surely an important part of his larger project of developing tourism in the Grandfather Mountain area. Morton’s photos of the festival in the 1940s-early 50s highlight both the crowd and the scene’s natural beauty.

Attendance grew rapidly in the convention’s early years; according to Hartley’s history of the event, the 1962 convention attracted 200,000 people and featured the Reverend Billy Graham as the preacher of the Annual Sermon (Hartley 14). Although the founder’s account of the numbers may be inflated, the convention had clearly evo lved into a major event, drawing talent from all over the country, including Johnny Cash, Roy Acuff, and Bob Hope throughout the 1960s and 70s. The 1976 convention was the setting for a prime-time Oral Roberts special directed by actor and comedian Jerry Lewis and featuring Roy Clark (who was then hugely popular as the co-host of the Hee Haw television show and a frequent guest host on the Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson), as well as members of the Grandfather Mountain Cloggers and singers from Richard Roberts’ (Oral Roberts’ son) choral group. That event was the occasion for a major upgrading of the facilities by Hollywood stage designer Fred Luff (Harris A11).

lved into a major event, drawing talent from all over the country, including Johnny Cash, Roy Acuff, and Bob Hope throughout the 1960s and 70s. The 1976 convention was the setting for a prime-time Oral Roberts special directed by actor and comedian Jerry Lewis and featuring Roy Clark (who was then hugely popular as the co-host of the Hee Haw television show and a frequent guest host on the Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson), as well as members of the Grandfather Mountain Cloggers and singers from Richard Roberts’ (Oral Roberts’ son) choral group. That event was the occasion for a major upgrading of the facilities by Hollywood stage designer Fred Luff (Harris A11).

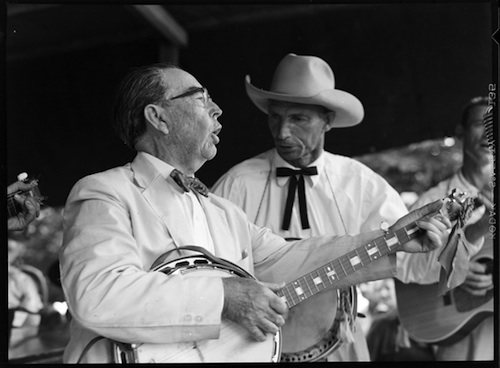

The Singing on the Mountain featured some of the finest exponents of regional traditions, known beyond the region largely through specialized documentary recordings, as well as nationally syndicated performers, often with North Carolina roots. Two examples of the first are George Pegram and Bascom Lamar Lunsford.

Lunsford was born in Madison County, just north of Asheville, North Carolina, in 1882, and he began playing fiddle and banjo at an early age with the encouragement of his teacher father and his ballad-singing mother. Through recordings by song collectors as early as 1922 through numerous recordings for the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress, Lunsford had a major influence on folk revivalists of the 1960s, and was a dedicated preserver of children’s songs, parlor songs, and slave spirituals. Like many of the entrepreneurs associated with the Singing, he pursued a wide variety of careers: according to Timothy M. Osment, “He was a fruit tree salesman and traveled the region with a Cherokee beekeeper. . . . During World War I, he moonlighted as an agent chasing draft evaders. In 1909, after finishing at Rutherford College he became a teacher. Later he would study law at Trinity College [now Duke University]. He passed the bar in 1913 and became a licensed solicitor — even working for several years with the NC Legislature.”

Lunsford was born in Madison County, just north of Asheville, North Carolina, in 1882, and he began playing fiddle and banjo at an early age with the encouragement of his teacher father and his ballad-singing mother. Through recordings by song collectors as early as 1922 through numerous recordings for the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress, Lunsford had a major influence on folk revivalists of the 1960s, and was a dedicated preserver of children’s songs, parlor songs, and slave spirituals. Like many of the entrepreneurs associated with the Singing, he pursued a wide variety of careers: according to Timothy M. Osment, “He was a fruit tree salesman and traveled the region with a Cherokee beekeeper. . . . During World War I, he moonlighted as an agent chasing draft evaders. In 1909, after finishing at Rutherford College he became a teacher. Later he would study law at Trinity College [now Duke University]. He passed the bar in 1913 and became a licensed solicitor — even working for several years with the NC Legislature.”

Pegram, the first artist (in 1970) to be recorded by Boston’s Rounder Records, now a major roots music recording company, is from Guilford County in North Carolina. After working in sawmills and furniture factories, he teamed up with Lunsford and began performing at various folk and dance festivals organized by Lunsford. His distinctive three-finger banjo picking (a North Carolina style that evolved into the bluegrass banjo styles of Earl Scruggs and Don Reno), as well as his entertaining stage personality won him multiple awards at the Galax fiddler’s convention.

One of the most famous musical personalities to be associated with the Singing on the Mountain was Arthur Smith, who organized the convention’s music program for 35 years. Smith’s popular radio shows on WBT in Charlotte during the 1940s were followed by national success in the early days of television. Morton took many photos of Smith and his band, the Crackerjacks, at the Singing on the Mountain and elsewhere; the two influential North Car olinians were close friends and business partners. Two years after WBT became WBTV, North Carolina’s first television station, The “Arthur Smith Show” began a 35-year run as the first live country music show to be syndicated nationally. Smith also achieved national fame as a musician when “Guitar Boogie” became a hit in 1948, and his banjo duet with Don Reno, “Feudin’ Banjos,” was notoriously plagiarized by Warner Brothers as “Dueling Banjos” in the 1973 film Deliverance. (Don Reno was a member of Smith’s band, the Crackerjacks, before making bluegrass history with Red Smiley and the Tennessee Cut-Ups).

olinians were close friends and business partners. Two years after WBT became WBTV, North Carolina’s first television station, The “Arthur Smith Show” began a 35-year run as the first live country music show to be syndicated nationally. Smith also achieved national fame as a musician when “Guitar Boogie” became a hit in 1948, and his banjo duet with Don Reno, “Feudin’ Banjos,” was notoriously plagiarized by Warner Brothers as “Dueling Banjos” in the 1973 film Deliverance. (Don Reno was a member of Smith’s band, the Crackerjacks, before making bluegrass history with Red Smiley and the Tennessee Cut-Ups).

Smith eventually won a landmark copyright infringement case for this composition that sold eight million copies in the first six months after its release. Journalist Ralph Grizzle speculates that the composition of “Feudin’ Banjos” was inspired by Smith’s involvement in his friend Hugh Morton’s fight with the North Carolina Highway Commission over the government’s attempt to condemn part of Morton’s land for a right of way for the Blue Ridge Parkway. In a televised debate with the highway commissioner, “Smith said that he believed a man had a right to do what he wanted to do with his own property. Smith went on to say that in his opinion Morton was taking good care of Grandfather Mountain and that he did not see what right a bunch of Washington bureaucrats had to take it away from him. The switchboard lit up with calls from viewers who phoned in to express their support for Morton” (Grizzle).

Although the Singing on the Mountain has declined in attendance somewhat since its heyday in the 1960s and 70s, the 86th annual event is on June 27, 2010, and features mainly regional gospel groups including the Cockman Family, the Carolina Quartet, and the Primitive Quartet. More information is at the Grandfather Mountain website.

–Dave Haney and Lisa Baldwin

REFERENCES

Church, Bonnie. “Pearl Hartley: Singing on the Mountain Since 1925.” Boone, NC: The Mountain Times (July 2, 1992): 23.

Grizzle, Ralph. “Guitar Man; Arthur Smith.” http://www.kenilworthmedia.com/cv/ourstate/people/arthur_smith.htm.

Harris, Harvey, “Unprecedented Changes Planned for Singing on the Mountain.” Greensboro Daily News (June 26, 1976): A11.

Hartley, J. L. The Mystery of the Brown Mountain Lights combined with Singing on the Mountain/ Walking for Health. Linville, N.C.: J.L. Hartley, [1962?]

Osment, Timothy. “Bascom Lamar Lunsford.” Digital Heritage.org (Western Carolina University Mountain Heritage Center). Posted April 30, 2008. http://www.digitalheritage.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=18&Itemid=46

Wolter, Beverly. “Hartley, Sing on Mountain’s Founder, Dies.” Winston-Salem Journal (March 1, 1966).

Thanks to Dean Williams and Mollie Surber in the Appalachian Collection at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina for assistance with the collection’s valuable archival material.

The 2014 “Singing on the Mountain” promises to be really special:

http://www2.wataugademocrat.com/Community/story/Singing-on-the-Mountain-welcomes-Leighton-Ford-id-015200

The 2016 “Singing on the Mountain” will be held on Sunday, June 26th at MacRae Meadows in Linville. This will be the 92nd gathering and to celebrate, “Our State” magazine, in the June issue, has a historical feature on the event. To support the article, there is a Hugh Morton photograph from the 1974 edition (link below).

http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/morton_highlights/id/2217/rec/20

The sad news from Tulsa, Oklahoma is that Country Music’s Ambassador, Roy Clark, has died. He was a photo subject of Hugh Morton in 1976.

https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/search/collection/morton_highlights/searchterm/Roy%20Clark%20/order/nosort