This essay was composed for the Worth 1,000 Words project by DAVID S. CECELSKI and TIMOTHY B. TYSON. David S. Cecelski is an independent historian and author of several books on North Carolina history, most recently The Waterman’s Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina (2001). Timothy B. Tyson is Senior Research Scholar at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, Visiting Professor of American Christianity and Southern Culture at Duke Divinity School, and holds an appointment in the American Studies Department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Tyson is the author of books including the memoir Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story (2004). Cecelski and Tyson were co-editors of the 1998 volume Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy.

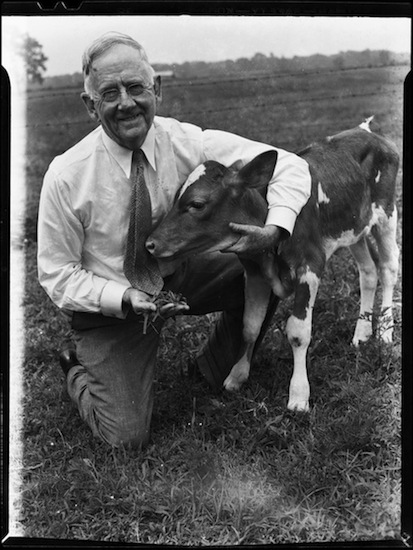

We can’t stop looking at Hugh Morton’s photographs of his grandfather. We see these fond images through our own eyes as grateful grandsons, adoring sons, and as loving fathers who want to be grandfathers ourselves. We also see them, though, as historians of our beloved North Carolina, an affection which we share with Hugh Morton.

We can’t stop looking at Hugh Morton’s photographs of his grandfather. We see these fond images through our own eyes as grateful grandsons, adoring sons, and as loving fathers who want to be grandfathers ourselves. We also see them, though, as historians of our beloved North Carolina, an affection which we share with Hugh Morton.

That is one reason why Morton’s photographs of his grandfather are so arresting to our eyes. These images of Hugh MacRae seize our attention as historians and as human beings. They do so all the more because a dozen years ago, we co-edited Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot and Its Legacy. That anthology marked the centennial of one of the South’s worst racial atrocities and Morton’s grandfather, Hugh MacRae, was a central figure in that terrible racial massacre.

In the fall of 1898, MacRae – an MIT-educated engineer, land developer, and textile mill owner – led a conspiracy to overthrow Wilmington’s elected leadership. A black and white political coalition called the “fusionists” had been elected to govern Wilmington and had launched a remarkable experiment in interracial democracy. There was no “Negro domination,” as MacRae and his colleagues charged, but in the state’s largest city, four of the ten city aldermen were black men.

To take back power in 1898, MacRae helped to organize a Vigilante Committee that intimidated blacks and their white allies from going to the polls. “If you find the Negro out voting, tell him to leave the polls, and if he refuses, kill him, shoot him down in his tracks,” Alfred Waddell, MacRae’s handpicked candidate for mayor, declared.

It was no secret that violence was on their minds. Two weeks before the slaughter in Wilmington, the Washington Post ran these headlines: “A City under Arms—Blacks to Be Prevented from Voting in Wilmington, N.C.—Prepared for Race War—Property-Holding Classes Determined Upon Ending Negro Domination.”

After Election Day, MacRae was a driving force in writing a “Declaration of White Independence” that demanded all-white rule. The next day, he and Waddell led heavily armed columns of white men into the city’s black neighborhoods and started killing African Americans. “Under thorough discipline and under command of officers,” one witness wrote, “capitalists and laborers marched together.” MacRae later boasted that they murdered “about ninety,” but the number of dead was probably smaller. It was hard to say, because many hundreds and perhaps a few thousand fled the city.

Afterwards, the white insurgents compelled the city’s elected officials to resign at gunpoint. They seized the local government, too. Though not elected by the voters, Hugh MacRae stepped forward as one of the city’s new councilmen. Many consider it the only genuine coup d’etat in U.S. history.

The “race riot” was the lynch pin in a white supremacy campaign that took power throughout North Carolina in 1898 and 1900. The victorious “white man’s party” disfranchised black citizens and built a rigid system of racial segregation. The new order excluded blacks from public life and denied them access to streetcars, restaurants, and other public accommodations that served whites. Their reign was not fleeting, either. The “white man’s party” remained in power for seventy years.

Though he remains a singularly important historical figure in North Carolina, neither of us had even seen a photograph of Hugh MacRae before. But Morton’s photographs seized us in a language more human than historical. It was powerful and provocative to see the warmth in MacRae’s eyes as he is photographed by his grandson and namesake, whom he obviously loved deeply. We love our grandfathers and our fathers, most of them no longer with us, and we relish their stories and miss their company. Their shortcomings do not define them. And so it was oddly ironic for two historians to appreciate and perhaps even envy these tender moments between the two Hugh MacRaes.

The publication of Democracy Betrayed and the wonderful commemoration of the race riot’s centennial that occurred in Wilmington in 1998 seem like a long time ago now. More than a decade has passed, but the public understanding of the white supremacy campaign’s centrality to the state’s history has grown unimaginably. Not that long ago, middle school libraries had a book that featured 12 of the state’s “greatest North Carolinians.” Along with Virginia Dare and the Wright Brothers, the book featured three of the white supremacy campaign’s leaders – Charles Aycock (later governor), Furnifold Simmons (later U.S. senator), and Josephus Daniels (publisher of the News & Observer).

the white supremacy campaign’s centrality to the state’s history has grown unimaginably. Not that long ago, middle school libraries had a book that featured 12 of the state’s “greatest North Carolinians.” Along with Virginia Dare and the Wright Brothers, the book featured three of the white supremacy campaign’s leaders – Charles Aycock (later governor), Furnifold Simmons (later U.S. senator), and Josephus Daniels (publisher of the News & Observer).

That book didn’t mention the Wilmington race riot of 1898, but credited the three with saving North Carolina from “Negro rule.” As late as 1991, the entry on Hugh MacRae in the standard work of North Carolina biography did not mention his leadership in the Wilmington race riot. Many eighth grade rs today still learn North Carolina history from a book that does not mention the race riot or the white supremacy campaign of which it was the capstone.

rs today still learn North Carolina history from a book that does not mention the race riot or the white supremacy campaign of which it was the capstone.

Things are changing, though. In the last decade, community activists in Wilmington sponsored one of the largest, most sophisticated, and most worthwhile commemorations of a racial atrocity in this country’s history, with generous contributions from Hugh MacRae II, suggesting that the MacRae family, at least, does not share the reluctance many people have to an honest assessment of our past. The Raleigh News & Observer published a special 14-page section, “Ghosts of 1898: Wilmington’s Race Riot and the Rise of White Supremacy,” which appeared in more than half a million daily newspapers. In addition, theatrical works, museum exhibits, community forums, a state government report, and several new textbooks have all confronted these events honestly. We could be wrong, but we suspect that nobody will soon be trying again to convince children that people like Aycock, Simmons or Daniels should be their heroes.

Unlike Alfred Waddell, the former Confederate officer who helped him lead the white mob in Wilmington, MacRae did not yearn for a return to the Old South. Far from it, MacRae was a sophisticated, visionary leader. Educated at some of the country’s best schools, he worked as a mining engineer and later took over his father’s cotton mill in Wilmington. A gifted entrepreneur and a farsighted builder, he established his own investment bank, real estate company, truck farming enterprise, and electric power company. Few men did as much to lead North Carolina into the 20th century.

That’s what fascinates us about Hugh Morton’s grandfather. Most prominent white supremacists argued that the Wilmington race riot and the white supremacy campaigns of 1898-1900 settled the state’s “race problem” for good. Flush with victory, Josephus Daniels hailed “permanent good government by the party of the white man.” On the eve of his gubernatorial election in 1900, Charles Aycock, too, was ready to move forward. He said that, “We have ruled by force, we can rule by fraud, but we want to rule by law.”

MacRae, though, wanted more. During the rest of his life, he, like the other mob leaders of 1898, remained a staunch segregationist, building whites-only suburbs and whites-only resorts like Wrightsville Beach. But that wasn’t enough; he also wanted to end the South’s reliance on black labor. He considered African Americans genetically unfit to serve as the foundation for the state’s 20th-century economy and tried to recruit “sturdy European stock” to settle here.

A believer in race-based eugenics, MacRae preached a gospel of immigration and agricultural innovation that, he held, might one day dispel the region’s reliance on black labor. The experimental farm communities that he founded in southeast North Carolina welcomed refugees from all over northern Europe, but he never allowed blacks or other dark-skinned people to settle in those communities. He consigned them to clearing land, digging ditches, and picking crops. That was Hugh MacRae’s vision of the New South.

Having learned so much about MacRae while we edited Democracy Betrayed, Hugh Morton’s portraits of him are absolutely arresting. They peer into the roots of many of our current racial dilemmas and into the past that we have inherited. His grandfatherly visage creates a moment for meditation on the nature of good and evil. And yet we are not entirely sure why we cannot stop looking at Hugh Morton’s grandfather. All we can say with confidence is that, caught in the lens of a loving grandson’s camera, the Hugh MacRae we see is a gentle, wise-looking old man who looks a lot like family – in fact, who looks a lot like us.

–David Cecelski and Timothy Tyson

What a thoughtful piece and a great reminder that all of us are filled with often vexing and irreconcilable contradictions. It behooves us not to forget that, about ourselves, or about those who become widely acclaimed and revered.

But I do have one question: what is the significance of the title? I don’t understand the reference to Invershiel — is it the Scottish one or the NC one, or? And what is the relationship of this reference to the piece? I wonder if the titling is going to prevent your piece from getting the readership it deserves.

Anne, I believe the use of the name Invershiel is in referece to the farm where the picture was taken. The relationship is best understood after learning and reflecting upon the historical facts that give relevace to the story .

You know, Anne, it seems sort of silly to answer your query almost two years later but, that aside, I think you make a good point. “Hugh MacRae at Invershiel” does not carry enough clear meaning for the work it sets out to do. I still like the essay, but I think you make a good point. Reading it again, I want about 250 more words to delve more deeply into the most interesting points–the nature of good and evil, history and nostalgia–that I think the essay shortchanges in its needless haste. And I want a new title for the piece, too, one that does more than evoke an obscure place and an obscure man, too, unfortunately. I will take this up with Dr. Cecelski, whom I am having coffee with later today. If he is game, perhaps we will rewrite this essay, taking more time to talk about 1898 and about how we navigate our personal attachments and our moral values, both as scholars and as citizens. So often we are tempted to let nostalgia and decorum limit the range of our honest explorations of the past. And other people or us at other times are so driven by anger and disappointment that we overlook the humanity of our demons and the demons of our humanity. It strikes me that David and I may have something worthwhile to say on this subject that transcends the scope of this essay. And if we do that, we will try to craft a title that does more work for the essay beneath it. Thanks, Anne.