It’s one of the most enduring legends of UNC history: a lone student, Hinton James, walking all the way from his home in Wilmington and arriving in Chapel Hill on February 12, 1795, where he reported to the one-building campus … Continue reading →

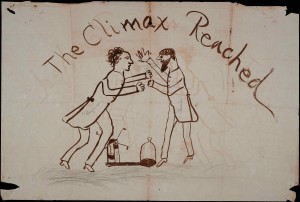

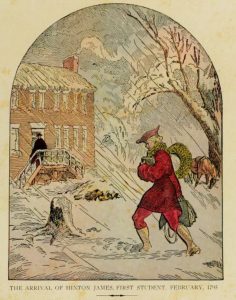

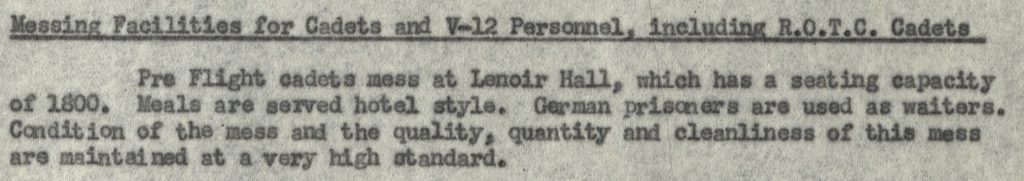

The arrival of Hinton James, as imagined by the 1935 Yackety Yack.

It’s one of the most enduring legends of UNC history: a lone student, Hinton James, walking all the way from his home in Wilmington and arriving in Chapel Hill on February 12, 1795, where he reported to the one-building campus and enrolled, becoming the first student at the University of North Carolina. But did he really walk all the way here?

We’re not sure. We checked all of the records and reports that we could find and, while there are no contemporary reports confirming James’s long walk to Chapel Hill, there’s nothing to refute the story, either.

We know for certain that UNC officially opened on January 15, 1795. It was reported to be a blustery day and must have been an odd ceremony because there were no students present. The campus remained empty of students for four weeks before James arrived. For the two weeks after that, he was the only student at the school. Others trickled in after that and by 1798 James was part of the first graduating class at UNC, when a grand total of seven students received their diplomas.

Entry from the Philanthropic Society Minutes, 1795 (probably not written by Hinton James).

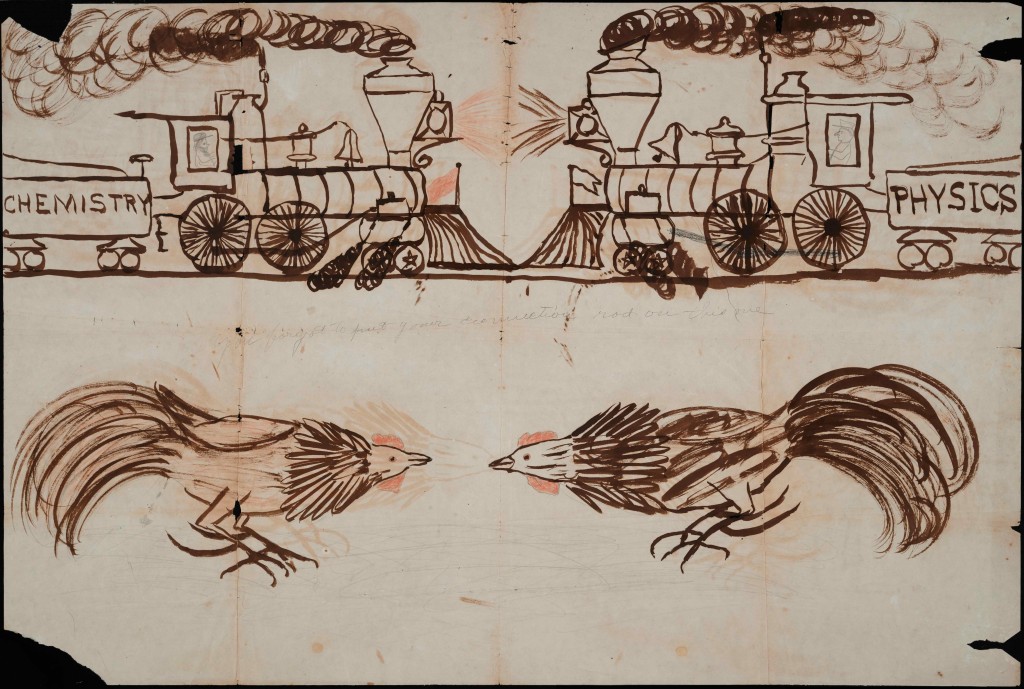

Hinton James did not have a lot of options for getting from Wilmington to Chapel Hill in 1795. We know he didn’t take I-40, and the arrival of railroads in North Carolina was still a few decades away. He probably traveled along recently established post roads to Raleigh and then found his way to Chapel Hill. For the long trip inland he could have taken a horse-drawn carriage, ridden on horseback, or, of course, walked. Given reports about the state of the roads during that cold, wet winter, a carriage was probably out of the question.

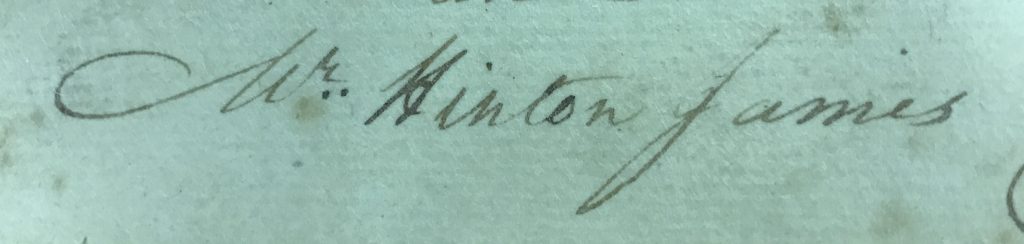

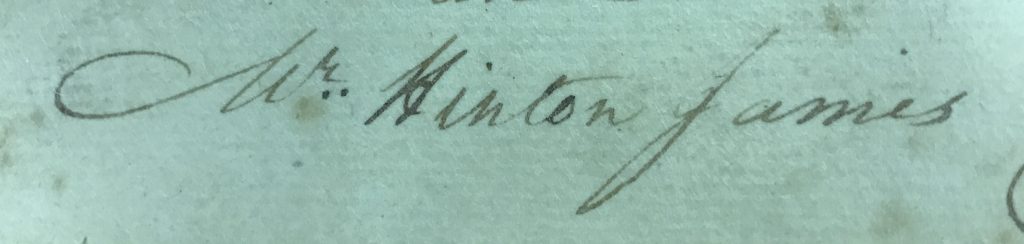

Hinton James’s signature from an 1838 letter reflecting on his time at UNC.

In the University Archives, there is a short account of the early days of the University written by Hinton James himself in 1838. He mentions the names of early professors and students and describes early exams, but does not talk about how he got to campus.

The earliest account that we’ve been able find, which mentions James’s mode of travel, was a speech by UNC history professor (and later President) Kemp Plummer Battle at University Day in 1880 (later reprinted in the 1886-1887 North Carolina University Magazine). Battle wrote, “Soon the first student came in — journeying all the way, hundreds of miles, from the Lower Cape Fear, on horseback doubtless, saddle-bags between his legs.”

Shirt from Hinton James Day, ca. 2010. From the UNC T-Shirt Archive.

Battle wrote about James in both volumes of his history of the University, though he told the story slightly differently in each. In the first volume, published in 1907, he wrote, “It was not until the 12th of February that the first student arrived, with no companion, all the way from the banks of the lower Cape Fear, the precursor of a long line of seekers after knowledge. His residence was Wilmington, his name Hinton James.” By saying that James arrived with “no companion,” Battle likely meant that he was the only student at the time. But this phrase may have been interpreted to mean that James made the entire trip by himself, a common detail in the story we often hear today.

After Battle’s history was published, the story began to take on the form we know today. Early 20th century issues of the Tar Heel mention James as the first student, but the first suggestion we could find of his having walked was in a 1908 article about the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies, which referred to “the time when Hinton James first tramped from Wilmington to Chapel Hill and found himself the only student on the campus.” (Tar Heel, 17 September 1908).

When Kemp Battle published the second volume of his history of UNC, in 1912, the story changed a little: “Thus it happens that Hinton James has gained immortal fame by being the first to trudge through the muddy roads of the winter of 1795, and presenting himself to the delighted gaze of the first presiding Professor, Dr. David Ker, exactly four weeks after the session began.”

Note that these don’t specifically say that he walked. Can one tramp or trudge on horseback? We’re not sure.

It didn’t take much longer for the myth to begin to take shape. A 1920 Tar Heel article said that “Hinton James established the Carolina long-distance walking record by tramping all the way from Wilmington so that he could be the first student to enter the University when it opened in 1795.” (Tar Heel, 20 June 1920).

While the story took hold, some still expressed doubt. At the University’s Sesquicentennial Convocation in April 1946, Victor Bryant, the chairman of the Legislative Committee on the Sesquicentennial, delivered the opening remarks. Bryant said, “We are told [Hinton James] had walked to Chapel Hill from his home in Wilmington, though I believe it possible that he did some hitch-hiking.”

In 2008, these UNC alums followed in Hinton James’s footsteps by walking all the way from Wilmington to Chapel Hill. (UNC News Services)

In Archibald Henderson’s 1949 book, The Campus of the First State University, James’s trek had the sound of a mythical journey: “The ambitious freshman of eighteen years, historic in primacy, trudged manfully more than 150 miles to reach the beckoning bourne of the State University on February 12, 1795.”

By the time William Snider published Light on the Hill, in 1992, there seemed to be no doubt about James’s long journey. Referring to the first student, Snider writes, “His name was Hinton James and he walked the entire distance from his native Wilmington to Chapel Hill to enroll.”

So, returning to our original question: did Hinton James really walk the whole way from Wilmington to Chapel Hill? We don’t know. There’s nothing in the University Archives that says he did, but there’s also nothing to prove otherwise. As we’ve seen, the earliest account says James “probably” came on horseback, and it took a while for the full walking story to emerge. However, it’s certainly possible that this is a true story that was simply carried orally through the generations. No matter how Hinton James got here, it had to have been a difficult trip and serves as an enduring inspiration to the the generations of students who have continued to follow him in their own journeys to Chapel Hill.