Officially it’s “The Dean E. Smith Student Activity Center.” Some call it simply “The Smith Center,” while others call it “The Student Activity Center.” And then there are those who lovingly call it “The Dean Dome.” But whatever name you use, the University of North Carolina’s basketball arena had a most interesting and inspiring beginning. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard takes a look back at the beginning of what has become one of the premier basketball facilities in the country.

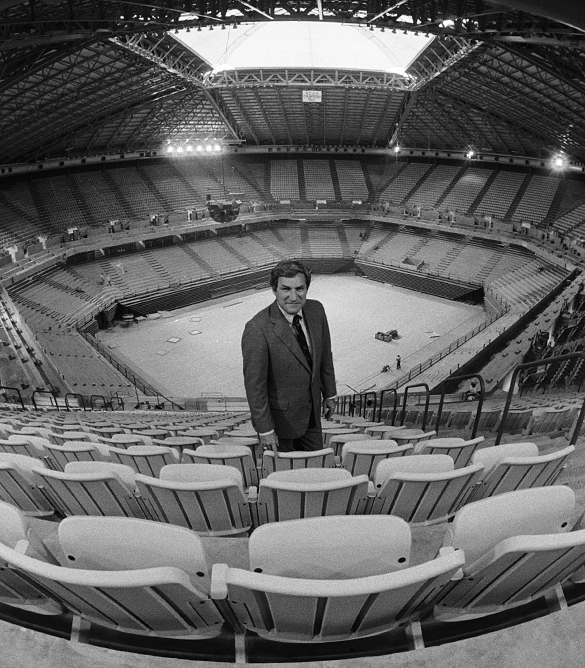

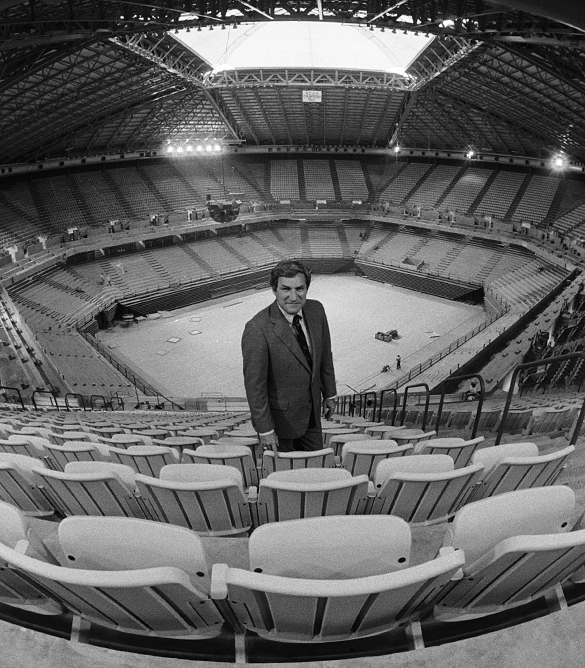

Dean Smith in the UNC Student Activity Center, 21 August 1985. (Photograph cropped by the editor.)

“The SAC (Student Activity Center) is a visible commitment to excellence in athletics.”—UNC Athletics Director John Swofford, Summer of 1985

The scenario was familiar. By 1980 Carolina had once again outgrown its basketball facility and talk of a new one was a familiar topic when Tar Heel alumni and friends gathered. It was just as it had been in 1923 when the Indoor Athletic Center (known as the Tin Can) replaced Bynum Gym—just as it had been in 1937 when Woollen Gym replaced the Tin Can, and just as it was in 1965 when Carmichael Auditorium replaced Woollen Gym.

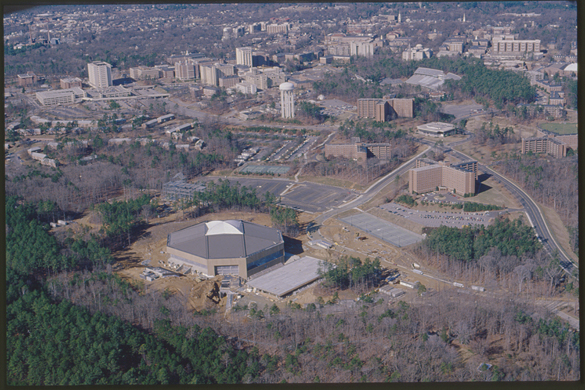

In the spring of 1980 the University and a very special group of its most loyal supporters began a journey, led by Hargrove “Skipper” Bowles, UNC Class of 1941. The mission was to raise 30 million dollars in private funds for an arena to showcase head coach Dean Smith’s nationally prominent basketball program. There were many who said it couldn’t be done, but Bowles never wavered and on April 17, 1982 ground was broken in a wooded ravine near Mason Farm Road. The fund raising campaign continued until August 1, 1984. By that date 2,362 people had contributed from $1 to $1 million, and the total came to almost $35 million. (The single $1 million gift came from businessman Walter R. Davis.)

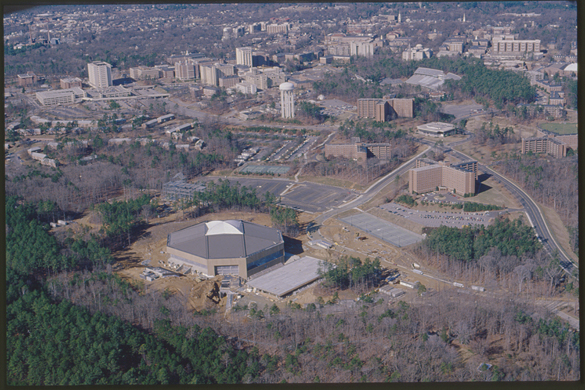

Aerial view of the Student Activity Center under construction circa 1985. (Hugh Morton photograph, not in online collection at time this post was published.)

While Bowles and his team made its final push, construction at the site was progressing—more than 20,000 cubic yards of rock were dynamited out of the ground and about 150,000 cubic feet of dirt was redistributed to clear and shape the land. Slowly the bricks and mortar and steel and concrete took shape. 1800 tons of structural steel was brought in to support the 250,000 square foot roof. After almost four years of construction, the 300,000 square foot octagonally shaped, seven-and-a-half acre Student Activity Center was ready.

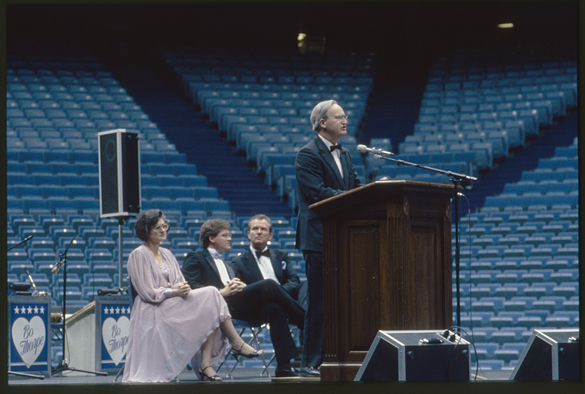

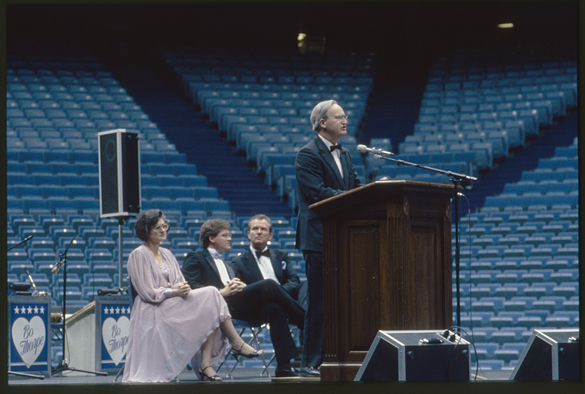

On Friday night January 17, 1986, a black-tie dinner was held in the new arena to honor the University’s Arts and Sciences Foundation. Broadcaster Woody Durham, master of ceremonies, introduced UNC’s Chancellor Christopher C. Fordham III.

UNC Chancellor Christopher Fordham III speaks during a black-tie dinner to honor the University’s Arts and Sciences Foundation. During his speech, Fordham announced that the Student Activity Center was to be named in honor of Dean Smith. Seated behind Fordham (left to right) are Gillian T. Cell, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, John Swofford, Director of Athletics, and Woody Durham, Master of Ceremonies. (Hugh Morton photograph, not in the online collection at the time this post was published.)

“This magnificent building stands as both a tribute to what Dean Smith has created at the University and a promise that what he has developed will continue. . . . We are a better university and a better state because he is one of us.” The Chancellor then added the following announcement. “From now on, this building shall be known as the Dean E. Smith Student Activities Center . . . .”

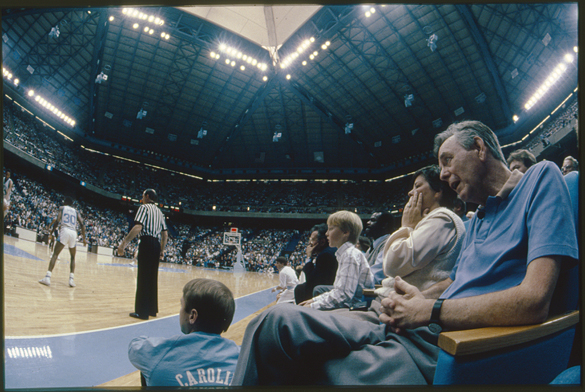

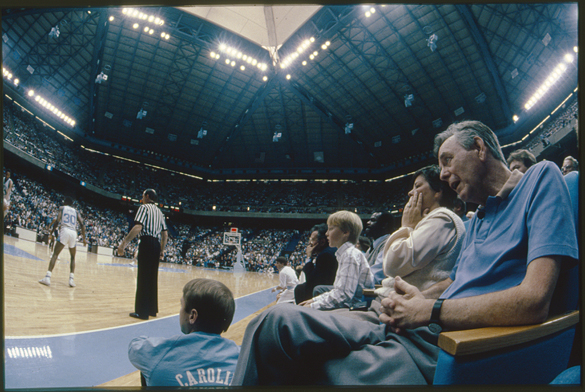

Hargrove “Skipper” Bowles watching the UNC vs. Duke basketball game during the Smith Center’s debut. Seated to Bowles’ right is his wife Deziree and grandson Sammy Bowles. (Hugh Morton photograph, not in the online collection at the time this post was published.)

During the fund-raising campaign, “Skipper” Bowles had been diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease. When he entered the Smith Center on Saturday afternoon January 18, 1986, Bowles was on a respirator and in a wheel chair. One of the first persons to greet him was North Carolina Governor Jim Martin.

Then it was time for Dean Smith’s number one ranked Tar Heels (17-0), led by senior James Daye, to take the floor for the first time in their new home. The third-ranked Duke Blue Devils (16-0) followed. At exactly 1:18 PM, Coach Smith walked into the arena and walked directly over the where Bowles was seated, took both his hands, leaned close and whispered, “Skipper, this wouldn’t have happened without you.” Bowles smiled broadly and then was helped to mid-court for the ceremonial toss to begin the game. Skipper’s grandson Sammy was there to help his grandfather.

The ceremonial “jump ball” toss before the first game at the Dean Smith Center, played between hosting UNC and visiting Duke University. Hargrove “Skipper” Bowles is seated in the wheelchair, with Skipper’s brother Richard Bowles behind and Skipper’s grandson Sammy Bowles (Erskine Bowles’ son) at his side. Carolina players in white are (left to right) guard Kenny Smith, jumping center Brad Daugherty, forward Warren Martin, and forward Joe Wolf (#24). Duke players in blue: jumping center Danny Ferry, forward Mark Alarie, guard Tommy Amaker (#4). (Hugh Morton photograph, not in the online collection at the time this post was published.)

The official toss to start the Duke versus UNC game in Smith Center (Note: Scoreboard 0-0.) Carolina players in white: (left to right) guard/forward Steve Hale (#25), forward Joe Wolf (#24), Brad Daugherty jumping center, forward Warren Martin (#54), and guard Kenny Smith. Duke players in blue: (left to right) guard Tommy Amaker (#4), forward Mark Alarie (#32), jumping center Danny Ferry (#35), and guard David Henderson (#12). (Hugh Morton photograph, not in the online collection at the time this post was published.)

It was a historic moment in North Carolina sports. With a packed house of 21,426 looking on, Carolina defeated Duke 95 to 92. The record book shows that Tar Heel Steve Hale scored a career high 28 points, and Kenny Smith and Jeff Lebo combined for 50 points. Brad Daugherty and Joe Wolf led a 38 to 30 rebounding advantage. The Heels went to 18 and 0.

Following the game several fans left the arena and headed out into what would become “Skipper Bowles Drive”; many others, including Bowles, stayed around just to take in the moment. “I was overwhelmed,” said Bowles softly. “I knew how big it was going to be, and I still was overwhelmed.”

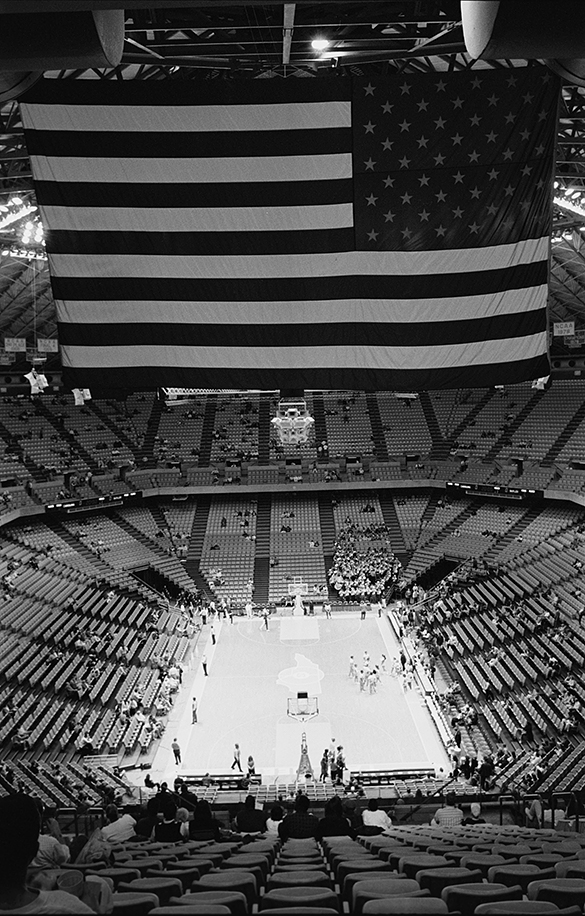

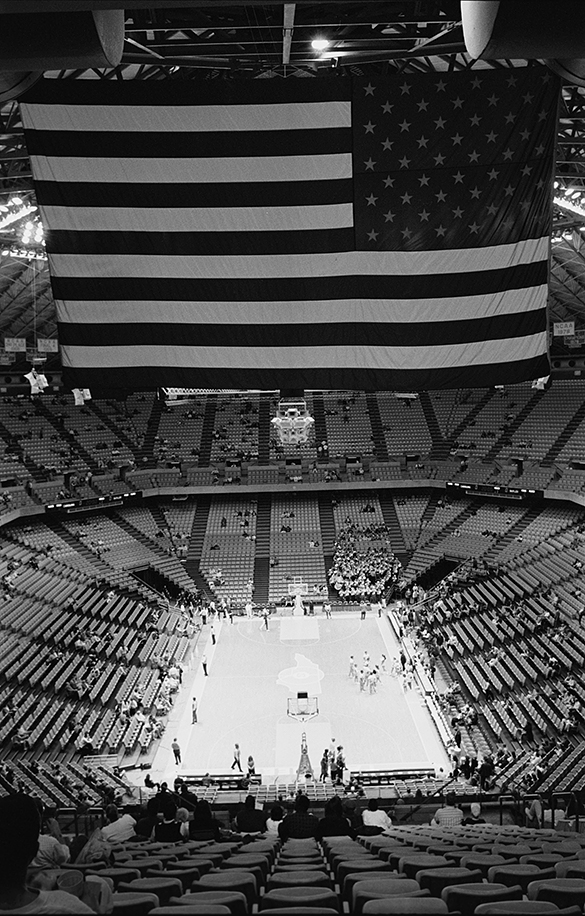

American flag hanging from rafters of Dean Smith Center. (Hugh Morton photograph made in January 1994.)

When photographer Hugh Morton entered the building for the first time he noticed that the American flag imported from Carmichael to the new facility was dwarfed in the spacious new building. So Morton took a flag catalog over to the basketball office and asked them to pick out a new, bigger one. Once in hand, Morton flew the flag over Grandfather Mountain, Mount Mitchell, the Biltmore House, the State Capitol, the USS North Carolina Battleship Memorial, Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, and the Wright Brothers National Monument. Satisfied that the flag now suitably represented the state of North Carolina, Morton handed it over to UNC, and it now hangs proudly over center court.

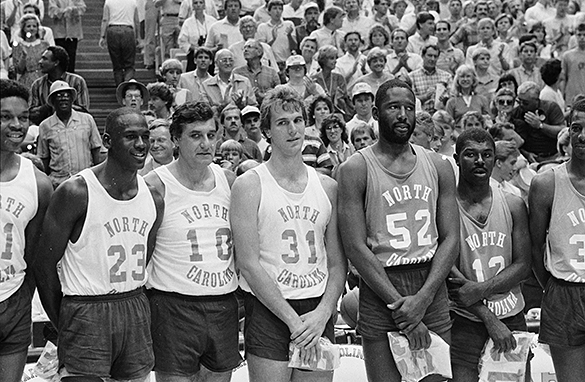

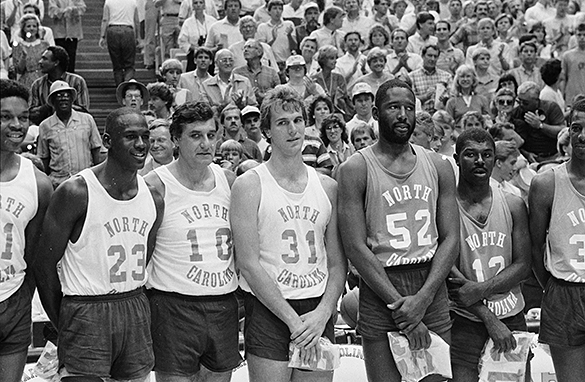

Notable UNC basketball alumni (left to right) Sam Perkins (#41), Michael Jordan (#23), Lenny Rosenbluth (#10), Mike O’Koren (#31), James Worthy (#52), Phil Ford (#12), and Charlie Scott (#33), who participated in the Smith Center Dedication Pro-Alumni Game, September 6, 1986.

The formal dedication ceremony for the Smith Center was held on September 6, 1986. A pro-alumni game was staged that afternoon, because Coach Smith wanted to celebrate the players who made the program great: Lenny Rosenbluth, Sam Perkins, James Worthy, Phil Ford, Michael Jordan, and many others came back to be a part of the dedication game. In his dedication remarks, Athletics Director John Swofford remembered what he called a sharp image from that first game in the Smith Center. “The image of “Skipper” Bowles and his grandson sharing a ceremonial ball toss just seconds before game time. It was altogether a nice moment for Bowles, his family, and all the people pulling for him. I was thrilled he could be there even if I did have a hard time keeping my own composure.”

The day after the dedication game, Sunday September 7, 1986, Hargrove “Skipper” Bowles, Jr. lost his battle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). He was 66 years old.

“Skipper” Bowles’ fingerprints are all over the Dean E. Smith Student Activity Center and the donors’ room is called Hargrove “Skipper” Bowles Hall. In an interview in early January, 1986 with Carolina Blue editor John Kilgo, Bowles looked back on the SAC effort. “That project was fun and I wouldn’t take anything for the experience. I don’t want but two things. I’d like to toss up the first ball in the building, and I’d like to see it named for Dean Smith.”

Both wishes came true.

Editor’s note: In the process of preparing this post, several images of the Dean Dome’s opening night festivities—both represented and not represented in the online collection— have been been discovered that were not previously identified. Not all of the descriptions for these images could be updated in the online collection and finding aid in time for publication. Once that work is completed they will be described in a more accurate manner to make them more easily discoverable. For an example, several pre-game photographs, including a photograph of Governor James Martin and others along the sidelines during the national anthem, can been seen by searching on their current title, “UNC basketball, wide-angle.” (<—click to see them!) Once the descriptions for these new discoveries have been cleaned up, this editor’s note will be updated; the work is likely to be gradual, however, so diehard Tar Heel fans may want to check back from time to time. More mysteries solved; more wishes coming true.

The early history of UNC’s controversial “Silent Sam” statue will be the topic of a free public lecture Jan. 22 at the Wilson Special Collections Library at UNC.

The early history of UNC’s controversial “Silent Sam” statue will be the topic of a free public lecture Jan. 22 at the Wilson Special Collections Library at UNC.