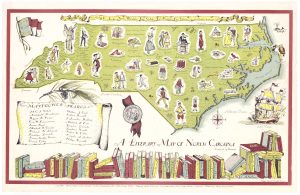

The devastating earthquake and tsunami in Japan sent us into the annals of North Caroliniana searching for tales of tremors in the Tar Heel state. There we found the story of Rumbling Bald Mountain, a series of tremors in 1874 that led locals to fear a volcano and drew the attention (and skepticism) of the New York press.

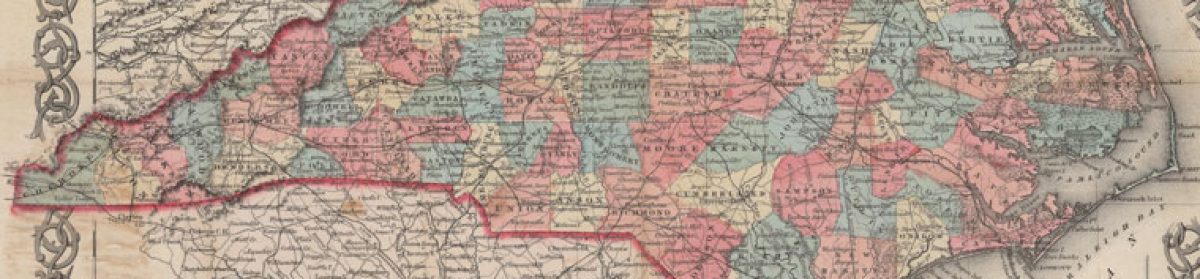

In early February 1874 residents near Chimney Rock in western Rutherford County reported feeling the ground shake and hearing loud booms coming from the direction of Bald Mountain, a 3,020 foot peak in the Broad River basin. Some claimed to see smoke and vapors coming from within the earth, giving rise to fears of a soon-to-explode volcano. Panic set in among the locals as tremors continued over the ensuing two months.

As word spread of strange happenings in the mountains, the press descended on the region and wrote of the religious fervor the tremors inspired. J. Timothy Cole, author of The Rumbling Mountain of Hickory Nut Gap: The Story of North Carolina’s Most Celebrated Earthquakes, writes that the most vivid accounts of the Bald Mountain earthquake and resulting panic are found in the Daily News of Raleigh, the New York Herald and the Asheville Western Expositor. Capt. E.C. Woodson of the Daily News reported that on the evening of February 9th a local preacher holding a religious revival prayed that God would move the ” ‘the strong hearts of this wicked people’ ” by causing ” ‘the mountain to shake and tremble beneath their feet.’ ” According to Woodson’s account, the first tremors near Bald Mountain occurred the following day.

Whether coincidence or divine intervention, the earthquake prompted more religious meetings and a revival-like atmosphere. The Western Expositor records that residents stopped work. “Cattle, horses and hogs were turned to the woods,” the paper reported, “And the entire people within range of this awful excitement have concluded that they have but a few more days to live.” The New York Times eventually printed a dispatch from a Knoxville reporter under the multi-line header “A Volcano in North Carolina. Extraordinary agitation of Bald Mountain.Terrible Sights and Sounds.The Terror-Stricken Residents Praying During Sixteen Days.” Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News also joined in the coverage.

The New York press’s interest in the story may have been little more than an attempt to sell papers or poke fun at the odd mountain folks south of the Mason-Dixon. Within days of running the first article about the tremors and possible volcano at Bald Mountain, the New York Times ran a second article suggesting that “the Bald Mountain Volcano, of North Carolina, has been regarded as a third-rate hoax.” The source of “this new sensation,” the Times suggested, was an Indian legend about “the original formation of the ridge known as Bald Mountain, or of an eruption which occurred many years ago.”

Wofford College professor Warren DuPre was sufficiently intrigued by the reports to mount an expedition to the region. Accompanied by a civil engineer, a preacher and about a dozen students, DuPre interviewed residents and hiked the terrain near Bald Mountain. During the course of its investigation, the team experienced several tremors firsthand. The group found no evidence of “gaping rocks, smoking peaks, sinking caverns, melting snows, etc, with which our newspapers have been teeming for many weeks past.” Eventually DuPre prepared a report for the Smithsonian Institution in which he ruled out rock blasting and electrical storms. But his explanation for the tremors was hardly conclusive. “The phenomena,” he wrote,”must be referred to that general volcanic or earthquake force, which seems as necessary to the economy of nature as light, heat or electricity.”DuPre’s words likely would not have calmed the fears of residents had the tremors not stopped by early May 1874.

Later investigators of the tremors have suggested that the rumblings may have resulted from rock falls occurring in a vast network of caves that lies under Bald Mountain. Scientists continue to investigate the plates and substrata that lie underneath North Carolina’s mountains and debate the seismic risks faced in this part of the country. But there seems little dispute as to the origins of the descriptor that sets Rutherford County’s Bald Mountain apart from similarly named peaks in Avery, Jackson, Wautauga, Yancey, Davidson and Orange counties. Rumbling Bald Mountain claimed its title in the winter of 1874.