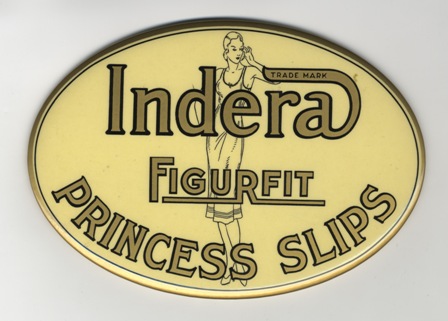

Indera Mills was incorporated in Winston-Salem in 1914. According to the company’s Web site, founder Francis Henry Fries took the name Indera from “an attractive Indian princess…whom he met while on vacation with his family in Egypt in 1907.”

In the beginning, Indera produced knitted slips and vests, union suits, knee warmers, and bathing suits. Today it specializes in thermal underwear.

In 1997, Indera Mills began outsourcing sewing to Monterrey, Mexico, and closed its factory in downtown Winston-Salem. The remaining work is done in Yadkinville.

This celluloid advertising piece, about 6 inches wide, was intended for display at store counters.