This Month in North Carolina History

Massachusetts native Henry Martin Tupper (1831-1893) attended Amherst College and Newton Theological Seminary before enlisting in the Union Army in 1862. After he was honorably discharged, Tupper requested that the American Baptist Home Mission Society of New York station him in the South so that he could work with former slaves.

The Tuppers arrived in Raleigh in October 1865. An anecdote recounted in Carter’s Shaw’s Universe reports that after travelling to Portsmouth, Virginia, Tupper and his wife stopped at a train station that had been partially destroyed during the Civil War, and purchased the first two tickets on the train to Raleigh after the tracks had been reconstructed. After establishing himself in Raleigh, Tupper began teaching Bible classes to former slaves in December. The classes were held in the Guion Hotel and aimed to teach African Americans how to read and interpret the Bible to prepare them to be Baptist ministers. In March of 1866, his wife began teaching classes to African American women in the Tupper’s home. Tupper quickly realized the need for education beyond theology courses, and set out to found what would eventually become Shaw University, the first black college in the South.

In February 1866, Tupper purchased land on the corner of Blount and Cabarrus Streets and built a two-story structure there that would serve both as a church and a school. Tupper used $500 that he had saved from serving as a Union soldier to help fund the land purchase. Significant financial assistance for construction was provided by the Freedmen’s Bureau and the New England Freedman’s Aid Society. On January 1, 1869, the Raleigh Theological Institute admitted its first class of fifteen seminary students. A year later, the school had outgrown its facilities and began making plans to expand. Through Tupper’s fundraising efforts and monetary support from Elijah Shaw (a woolen manufacturer from Massachusetts) and the Freedmen’s Bureau, funds were secured to purchase an estate in the center of Raleigh. Upon relocating, the school changed its name to the Shaw Collegiate Institute. In 1875 the school officially became incorporated as Shaw University.

Shaw University was co-educational from the beginning. A dormitory for men was built in 1871-1872, and, the first dormitory for African American women – Etsey Hall – was constructed on Shaw’s campus in 1874. Shaw University claims several other firsts, including Leonard Medical School, which was the first medical and pharmacy school that trained African Americans in the state of North Carolina, and, in 1888, the only law school for African Americans in the South. The 1878-1879 Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Shaw University reports that there were a total of 152 males and 115 females enrolled in various courses of study for that particular school year. During the 1878-1879 academic year, the majority of students were from North Carolina, but students from anywhere could enroll – several students were from Virginia and South Carolina, and one was from New Jersey.

At Shaw Collegiate Institute, Tupper served both as an administrator and instructor of the school and pastor of the church. He taught lessons during the day and night school classes. Managing both the school and the church gave rise to conflict for Tupper, and in 1870, people claiming to be trustees of the Second Baptist Church brought a suit accusing him of defrauding the church. The various charges suggested intrigue and internal politics relating to Tupper’s funding and administration of the church and the school and the wronging of African American church members. The law suit lasted until 1875 when a verdict was given in Tupper’s favor. Despite the lawsuit and other setbacks, Tupper oversaw the growth and expansion of the University and advocated for access to higher education for African Americans until he died in November of 1893. Tupper was buried on the campus grounds, and Dr. Nickolas Franklin Roberts, an African American and a graduate of Shaw University, was named acting president.

Sources:

Carroll, Grady Lee Ernest, Sr. They Lived in Raleigh: Some Leading Personalities from 1792 to 1892. Raleigh, NC: Southeastern Copy Center, 1977.

Carter, Wilmoth A. Shaw’s Universe: A Monument to Educational Innovation. Raleigh, NC: Shaw University, 1973.

Kearns, Kathleen, and Dayton, Michael J. Capital Lawyers: A Legacy of Leadership. Birmingham, AL: Association Publishing, 2004.

Shaw University. Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Shaw University, 1878 and 1879. Raleigh, NC: Edwards, Broughton & Co., Printers and Binders, 1879.

Image Sources:

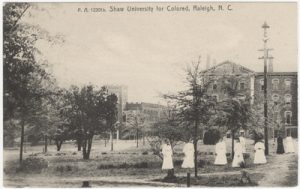

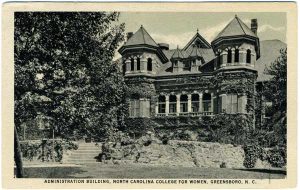

“Shaw Building, Shaw University, Raleigh, N. C.” in Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

“Shaw University for the Colored, Raleigh, N.C.” in Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

“Shaw University, Raleigh, N.C.“, Wake County, North Carolina Postcard Collection (P052), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

Shaw University brochure 1974, from [Shaw University Announcements, Bulletins, Programs, etc.] VC378.9 M67 Shaw 1874-.