This Month in North Carolina History

On July 18, 1963, the state of North Carolina began an “all-out assault on poverty” with the incorporation of the North Carolina Fund. The North Carolina Fund was an innovative program designed, administered, and operated by local communities. It was the first project of its kind in the country.

On July 18, 1963, the state of North Carolina began an “all-out assault on poverty” with the incorporation of the North Carolina Fund. The North Carolina Fund was an innovative program designed, administered, and operated by local communities. It was the first project of its kind in the country.

In the early 1960s, many North Carolinians were in trouble. Historians James L. Leloudis and Robert Korstad describe the economic conditions in the state when Governor Terry Sanford took office in 1961:

North Carolina’s factory workers earned some of the lowest industrial wages in the nation; thirty-seven percent of the state’s residents had incomes below the federal poverty line; half of all students dropped out of school before obtaining a high school diploma; and one-fourth of adults twenty-five years of age and older had less than a sixth-grade education and were, for all practical purposes, illiterate.

By 1960 the state’s rate of growth had been falling for decades, in part because of heavy emigration due to the declining number of agricultural jobs. Governor Sanford promised to experiment with new programs and ideas in order to enable North Carolinians to compete in a rapidly changing society.

The North Carolina Fund was established as an independent, non-profit corporation. Incorporated on July 18, 1963, by Governor Sanford, Charles H. Babcock, C.A. McKnight and John H. Wheeler, the Fund was financed by a seven million dollar grant from the Ford Foundation and by additional funding from Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation and the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation.

Having secured funding and organized a Board of Directors and Executive Committee composed of many of the state’s most prominent citizens, the agency established program offices in eleven urban and rural counties across the state. This decentralized structure was designed to permit each office to coordinate locally administered public and social services and to assist the poor by developing an approach unique to each community’s needs.

In 1964, Lyndon Johnson successfully pushed the U.S. Congress to pass the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act — a piece of legislation shaped both by Governor Sanford and Executive Director George Esser and the experience of the nascent North Carolina Fund — and the direction of the state’s antipoverty initiative took a new turn. On May 7, 1964, President Johnson, accompanied by Governor Sanford, visited the home of tenant farmer William D. Marlow near Rocky Mount, to promote the President’s “War on Poverty.”

This new national program, the cornerstone of which was the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), would administer millions of dollars in federal funding for the creation of local anti-poverty projects across the country and offered the possibility for expanding existing anti-poverty efforts. As the OEO called for the creation of community action programs developed with the help of the people the programs would serve, the North Carolina Fund instructed its own local programs to submit proposals to the federal agency with an increased emphasis in grassroots community development. Within a year of the Fund’s incorporation a number of these applications were approved and many local offices soon became not only federally-funded Community Action Agencies but partners in the national War on Poverty.

The North Carolina Fund developed a variety of programs across the state, including: the North Carolina Volunteers, a service corps initiative that trained college students to work in rural communities; a program to train community action technicians (CAT) to work in North Carolina and Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA); a summer internship and curriculum development program; academic research on poverty and economic development in North Carolina; daycare, home, and lifestyle management programs such as sewing and cooking classes, tutoring for school children, and adult literacy programs; community action and civic engagement programs; manpower and economic development initiatives such as Head Start and Neighborhood Youth Corps programs; and low-income housing development.

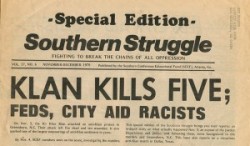

Over the next five years the Fund’s staff and volunteers touched the lives of countless North Carolinians and its programs and services affected communities across the state. However, many lawmakers began to question the uses of Fund resources and services, especially when some North Carolina Fund programs became involved with local black freedom movements. By 1968, according to historians Leloudis and Korstad,

“[T]he Fund’s future was in peril. “The agency “had expended its initial foundation grants, which had been awarded for a five-year period, and the national War on Poverty was under siege. When the Fund’s philanthropic backers offered to extend their support, its leaders declined. In part, they held to a vision of the Fund as a temporary and experimental agency. The founders had no desire to see their work routinized; to allow such a development, they insisted, would be to sacrifice innovation to the very forms of inertia that had for so long crippled the nation’s response to its most needy citizens.”

At the end of 1968 the North Carolina Fund disbanded, spinning off many of its successful state-wide programs into independent non-profit organizations.

Suggestions for further reading:

James L. Leloudis and Robert R. Korstad, “Citizen Soldiers; The North Carolina Volunteers and the South’s War on Poverty,” in Elna C. Green, ed., The New Deal and Beyond: Social Welfare in the South since 1930 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003), pp. 138-162.

LeMay, Erika N. “Battlefield in the Backyard: A Local Study of the War on Poverty.” M.A. Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1997

Alt, Patricia Maloney. “The Evolution of Community Action: Training Goals and Strategies of the North Carolina Fund.” M.A. Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1971.

Archival Resources:

North Carolina Fund Clippings: People, General Articles, and History of the Fund, 1963-1969. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

North Carolina Fund Records (#4710). Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Billy Ebert Barnes Collection (# 34), containing a number of photographs of North Carolina Fund people and activities. North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) (Series O. Foundation History). Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

George H. Esser Papers (#4887). Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.