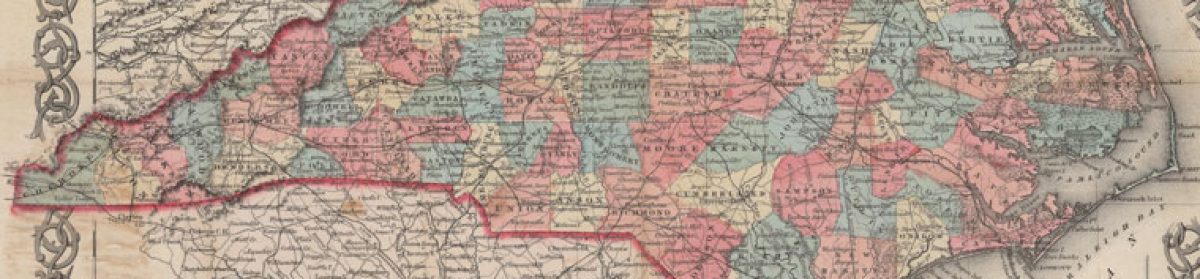

“Outside of East Tennessee the most extensive antiwar organizing took place in western and central North Carolina, whose residents had largely supported the Confederacy in 1861. Here the secret Heroes of America, numbering perhaps 10,000 men, established an ‘underground railroad’ to enable Unionists to escape to Federal lines.

“The Heroes originated in North Carolina’s Quaker Belt, Piedmont counties whose Quaker and Moravian residents had long harbored pacifist and antislavery sentiments. Unionists in this region managed to elect ‘peace men’ to the state legislature and a member of the Heroes as the local sheriff. By 1864 the organization had spread into the North Carolina mountains, had garnered considerable support among Raleigh artisans and was even organizing in plantation areas (where there is some evidence of black involvement in its activities).

“Confederate governor Zebulon Vance dismissed the Heroes of America as ‘altogether a low and insignificant concern.’ But by 1864 the organization was engaged in espionage, promoting desertion and helping escaped Federal prisoners reach Tennessee and Kentucky….

“Most of all, the Heroes of America helped galvanize the class resentments rising to the surface of Southern life. Alexander H. Jones, a Hendersonville newspaper editor, pointedly expressed their views: ‘This great national strife originated with men and measures that were … opposed to a democratic form of government.… The fact is, these bombastic, high-falutin aristocratic fools have been in the habit of driving negroes and poor helpless white people until they think … that they themselves are superior; [and] hate, deride and suspicion the poor.’ ”

— From “The South’s inner Civil War” by Eric Foner, American Heritage, March 1989