“Angels are bright still,” Shakespeare writes, “though the brightest fell.” This moment in Macbeth, when Malcolm debates with himself whether he should trust Macduff, maps Malcolm’s internal, political concerns onto a very real religious concern for Protestants in England: the outward appearance of evil. Malcolm believes that even though evil constantly attempts to look good, good must always appear to be good, too. Therein lies the problem: how does one distinguish between what appears to be good, and what actually is? How does one know whether they are working for something godly or for the Devil?

The western tradition still considers the figure of Satan as the multifarious and malevolent author of evil. In his seminal, multi-volume portrait of what the idea of “the Devil” evokes, Jeffrey Burton Russell suggests that the Devil isn’t a finite figure; instead, he argues,

The Devil is the personification of the principle of evil. Some religions have viewed him as a being independent of the good Lord, others as being created by him. Either way, the Devil is not a mere demon, a petty and limited spirit, but the sentient personification of the force of evil itself, willing and directing evil (Devil 23).

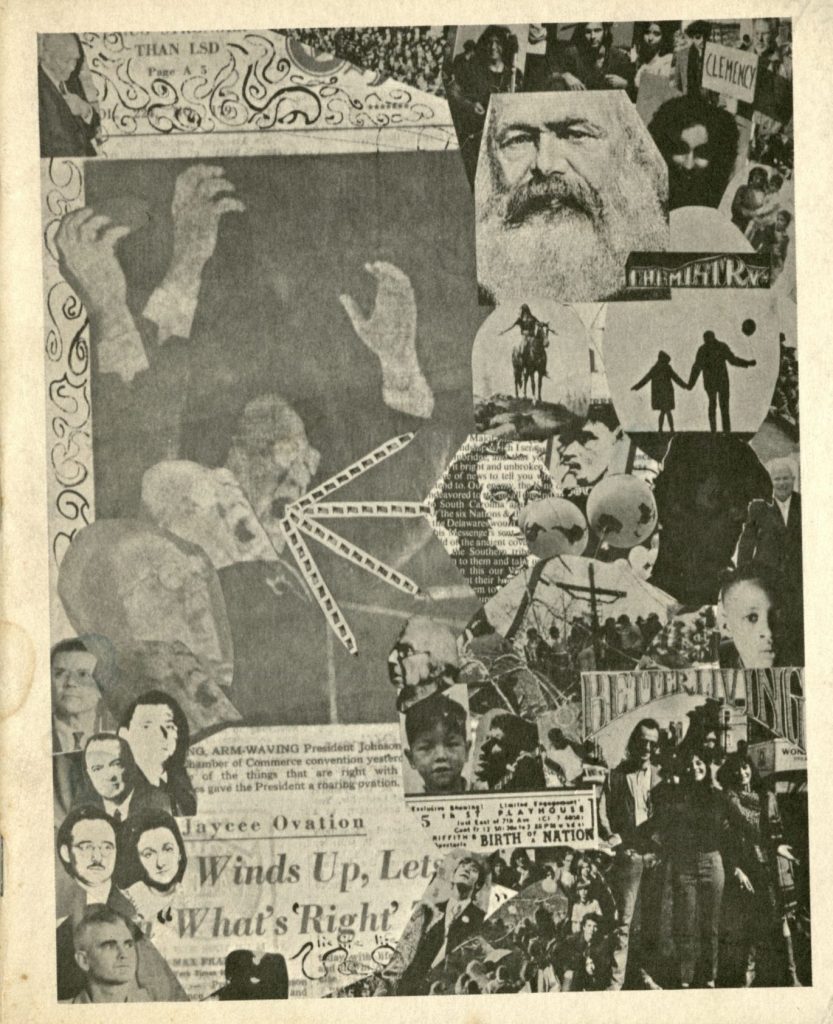

Nevertheless, across religious and secular traditions, the Devil remains a symbol of rebellion, heresy, accusation, and turpitude. Cultural representations of the Devil in literature and its accompanying visuals continue to define, condense, and even localize the measureless potential for evil. The text and images in these books never stop attempting to confine the unconfinable.

Who or what, then, is the Devil? And how would we actually recognize him if he showed up?

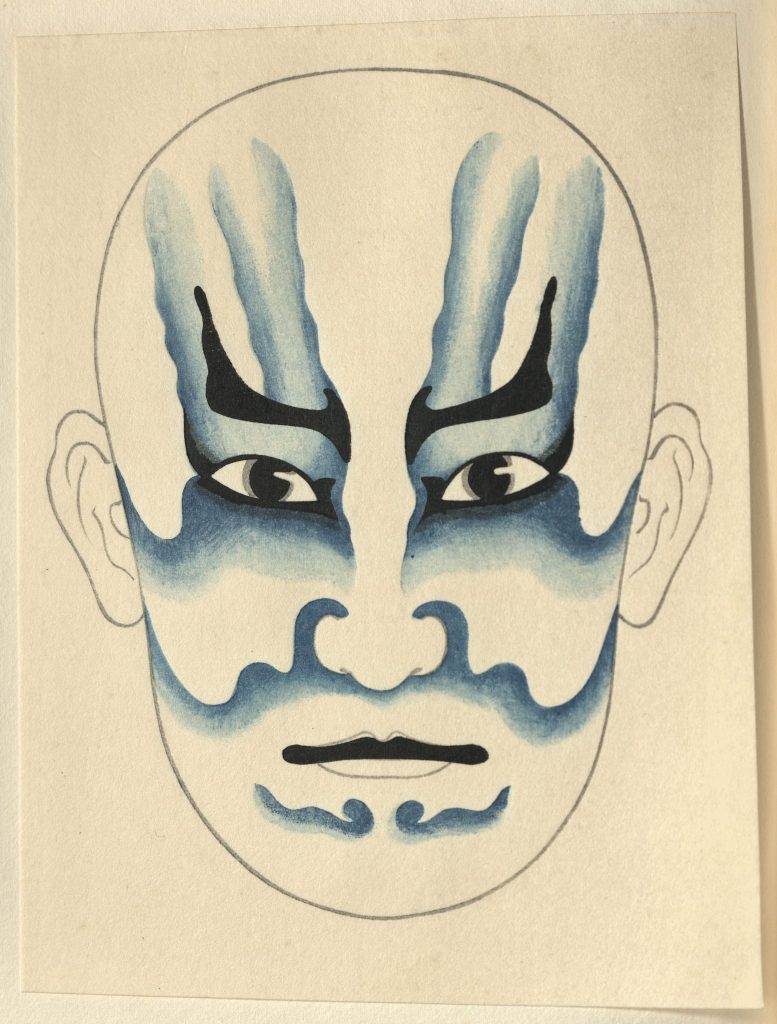

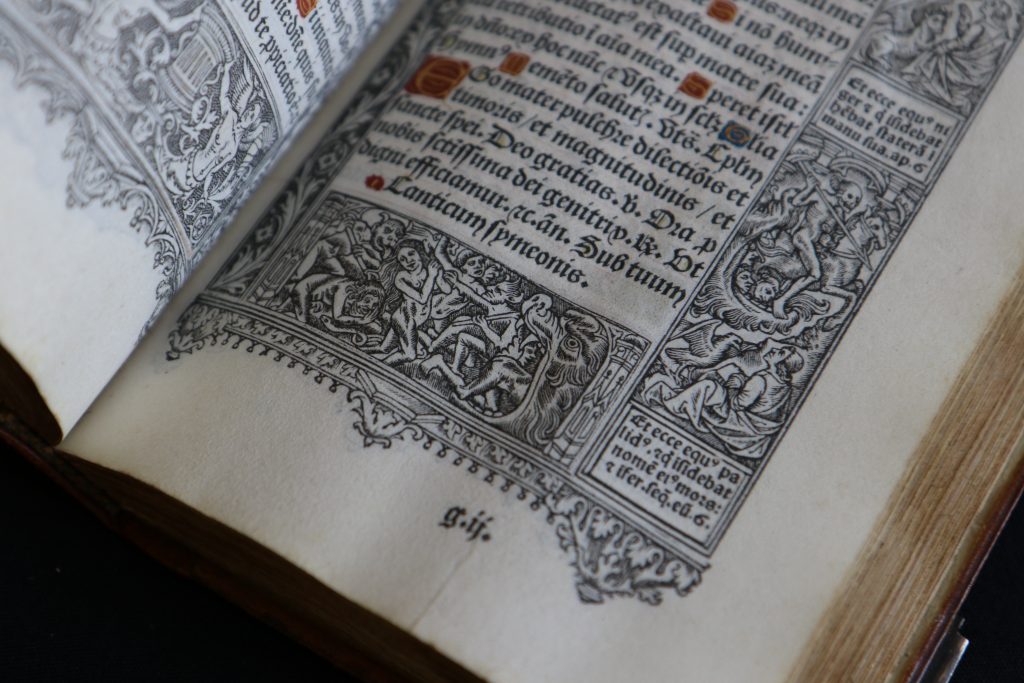

The Apocalypse long loomed over the religious life of Western Europe. From the rise of the early Church to the Protestant Reformation, Christian life anticipated the Second Coming, and it involved daily interactions with the divine, and the demonic, as a result. The general population understood the spirit world to be intimately tied to their own, and ecclesiastical authorities attempted to exert control over how their congregations perceived and interacted with that world. Canon scripture does not describe Satan, so early and medieval Christian artists had to develop an iconography that captured the Devil’s evolving role as tempter, tyrant, and rebel angel. They had to visually embody evil. Within centuries, the Devil acquired his characteristic hooves and horns, icons drawn from the Greco-Roman Pan and Jewish seirim that Western Christian artists grafted onto the demonic. And ecclesiastical authorities made sure that that iconography accompanied the texts moving out of scriptoria.

The early modern period further intensified the early and medieval Church’s demonological iconography. The visual tradition remained in print, even during the far more iconoclastic Protestant Reformation. Protestants emphasized the written word over Catholic visualization and ceremony, but they proved themselves the masters of the accompanying image, too. Using well-established visual rhetoric, Protestants developed an effective way to deliver their anticlerical, reforming message. Even before Martin Luther distributed his Theses on Halloween 1517, critics of the Papacy lampooned it with demonic imagery. This provided Protestants a range of visual sources to capitalize on and modify. In their hands, the Catholic image of the Devil would become the Catholic hierarchy of offices itself. But in prose, the Protestants argued that the Devil was terrifyingly mutable and, therefore, far more difficult to recognize.

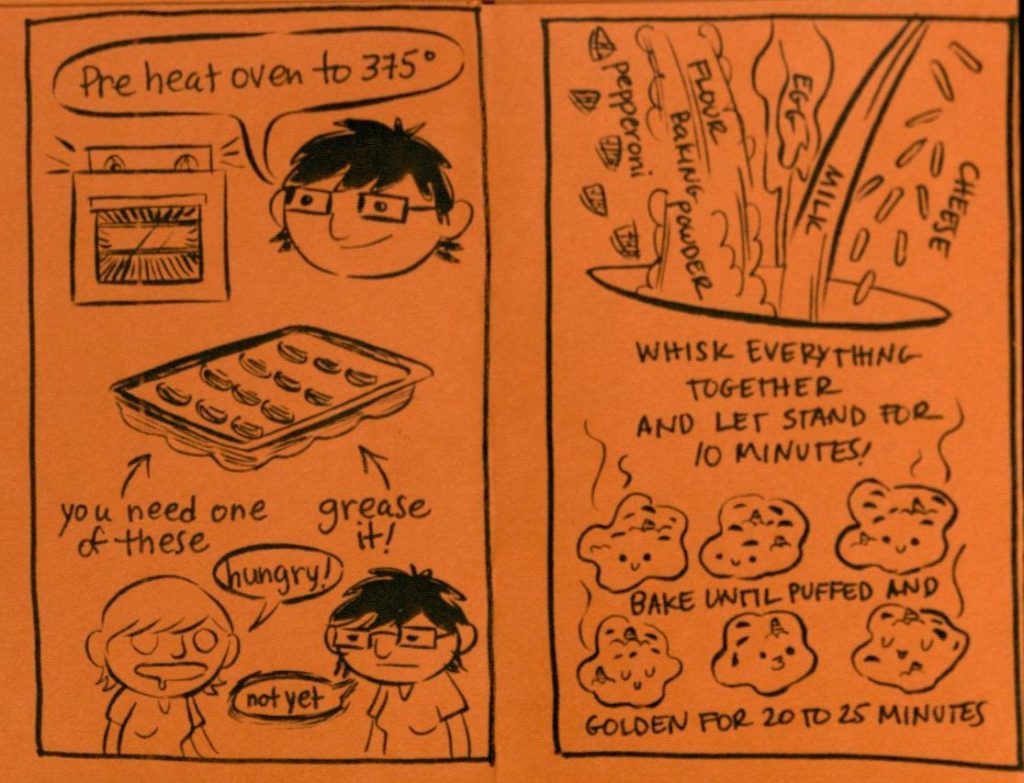

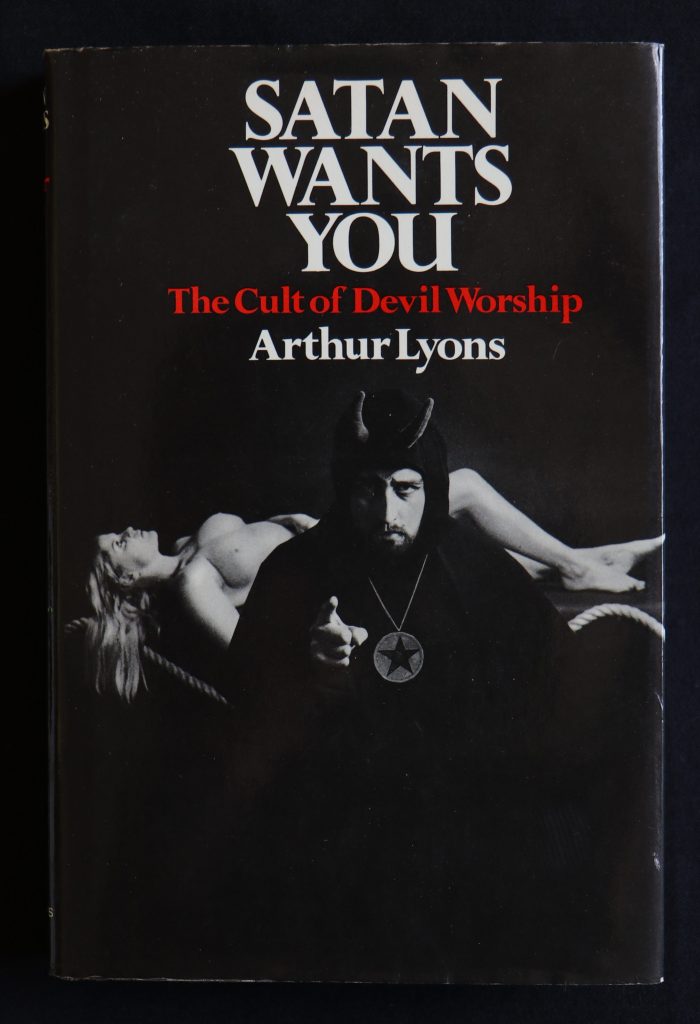

Arthur Lyons’s Satan Wants You, the Thielman Kerver Heures a lussaige de Rome, and M.M. Sheĭnman’s Вера в дьявола в истории религии will be on display in the Fearrington Reading Room at Wilson Special Collections Library as part of RBC’s Hallowzine event. Please join us on Thursday, October 31, from 3:00-4:30 pm for more spooky books, zine-making fun, and a book-themed costume contest with a generous prize for best costume!