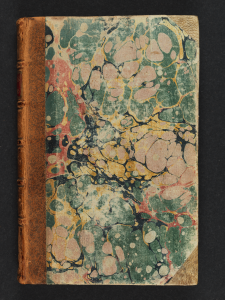

![]() One of the Rare Book Collection’s most interesting chronicles of the African diasporic experience exists not as an autobiography, but as a collection of letters. Originally published in 1782, our two-volume first edition of the Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho highlights the unique societal influence of a black public intellectual in 18th century England.

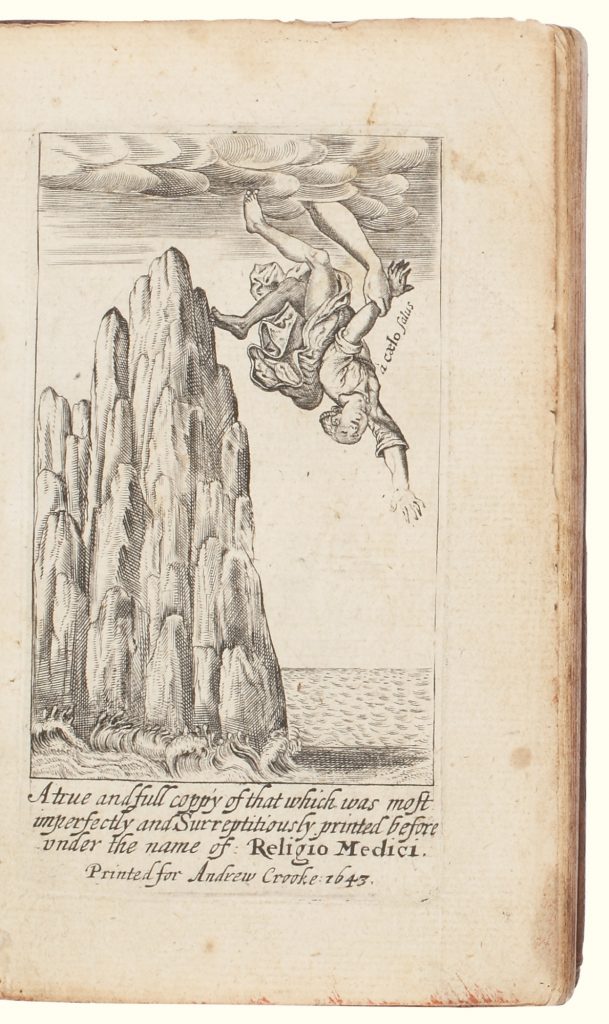

One of the Rare Book Collection’s most interesting chronicles of the African diasporic experience exists not as an autobiography, but as a collection of letters. Originally published in 1782, our two-volume first edition of the Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho highlights the unique societal influence of a black public intellectual in 18th century England.

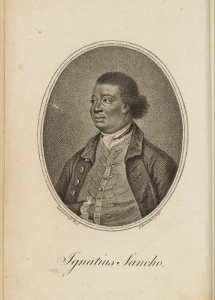

When these letters were published by an editor two years after his death, Ignatius Sancho posthumously became the first black Briton to publish correspondence. This was the last in a lifelong record of firsts: Sancho had been the first black Briton to vote in parliament, patronize a white artist, critique art, literature, & poetry, and have an obituary in the British press. He wrote plays, music, essays, and a book, and was well-published in popular serials. Known for his taste level, his creative opinion was sought after by the likes of Laurence Sterne, Matthew and Mary Darly, John Ireland, Daniel Gardner, John Hamilton Mortimer, Joseph Nollekens, and John James Barralet. Much of this status was afforded to him by his high station under the Duke and Duchess of Montagu, as well as his later ownership of a grocery (which afforded him his voting rights). These achievements were especially significant for a former slave, so much so that Abolitionists widely held him as a symbol of the high capacity of the black intellect. A master writer and rhetorician, he used his talents as a tool to gain respect and penetrate social circles previously inaccessible to black men.

We know that the public held him in high regard because it is indicated in the narrative framing of his Letters. The book begins with a disclaimer that was common in the publications of well-established white figures, but largely absent in those of black writers. The publisher’s note declares, “The editor of these letters [Frances Crewe Phillips] thinks proper to obviate an objection, which she finds has already been suggested, that they were originally written with a view to publication.” University of Maryland professor Vincent Carretta identifies this as an example of “the frequent and usually disingenuous disclaimer by editors of posthumously published correspondence that the letters had not been written with an eye toward publication.” These statements were intended to assert an authenticity of sentiment, countering public suspicions of self-censored and intentionally impressive writing. The fact that Sancho’s letters included such an opening, while equally significant publications by other black writers such as Olaudah Equiano and Frederick Douglass did not, offers us proof of a status and high regard that may otherwise be difficult to fully understand today. It is evidence of an established reputation for wit and artistry that preceded him even in death.

Sancho’s book of letters and other autobiographic black narratives are available in the Rare Book Collection. If you are interested in black experiences in the United States, check out our new exhibit “On the Move: Stories of African American Migration and Mobility,” on display until January 19th, 2020 in the Melba Remig Saltarelli Exhibition Room.