Here at the Rare Book Collection, we are fond of noting that one of the surest ways for a book to become rare is for it to be banned. Controversial books and those made scarce by suppression, they often find their final resting places at the RBC and other rare book repositories.

For Banned Book Week this year, we turn to some of the volumes in our new exhibition at Wilson Library, Chronicles of Empire: Spain in the Americas. This evening, October 1, at 5:30 p.m., there will be a special viewing of the show before a public lecture by Dr. David Stuart, the renowned expert on Mayan writing. At that time, the public is invited to tour the exhibition, which documents Spain’s exploration and settlement of the New World.

Just fourteen years before Columbus’s discovery of America, a papal bull had established the Spanish Inquisition to fight heresy. Eventually, the censorship of reading matter became one of the Inquisition’s central activities. The Catholic Church had sought to control the circulation of texts from the early fifteenth century on, and with the advent of printing, efforts were intensified. In the 1540s the universities at Paris and Louvain published indexes of prohibited books, and the Spanish Inquisition issued its own version in the 1550s.

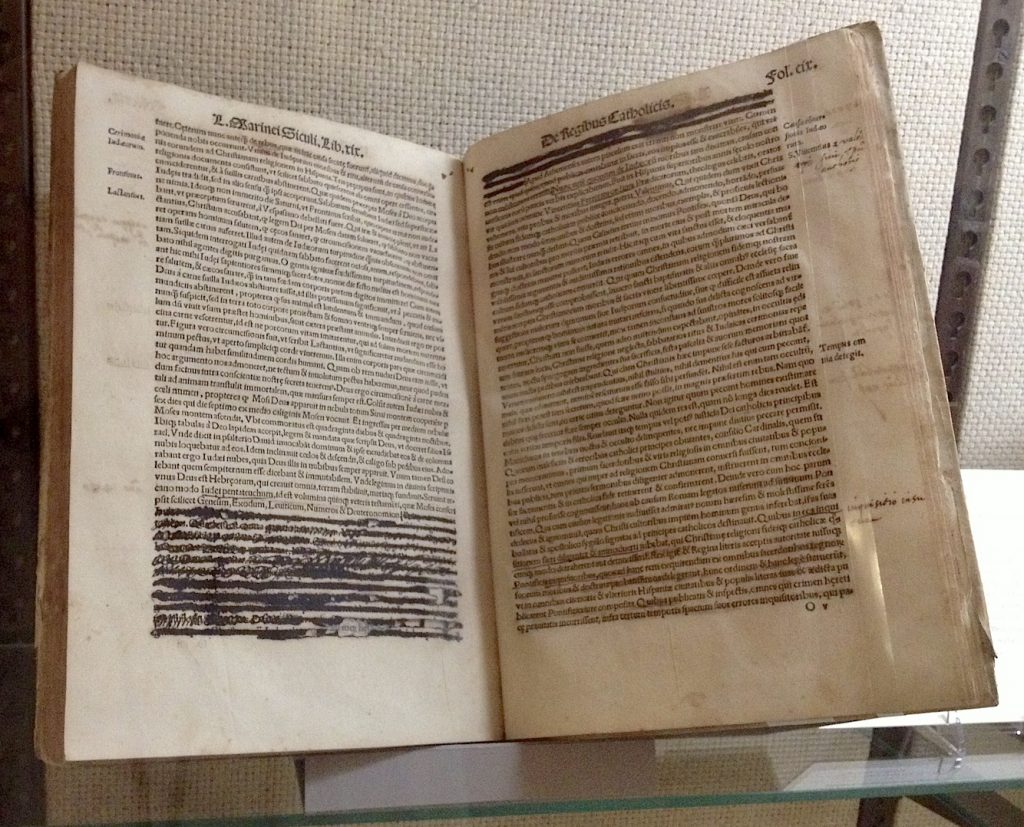

In the 1580s, with so many “objectionable” passages in texts having been identified, the Inquisition embarked on the compilation of a new kind of index, one of books to be expurgated. The inked-through example above is an official history of Spain by the Sicilian-born scholar Lucio Marineo. It is open to a section on the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella and a discussion of those Jews who had converted to Christianity but practiced Judaism secretly. Such Jewish converts were the primary targets of the Inquisition in its early years. A manuscript note on the title page, by Fr. Decio Carrega, tells us that he has expurgated lines of text that were condemned by the Spanish Inquisition. Carrega, active in the early seventeenth century (close to a hundred years after the book’s publication), was a Dominican inquisitor.

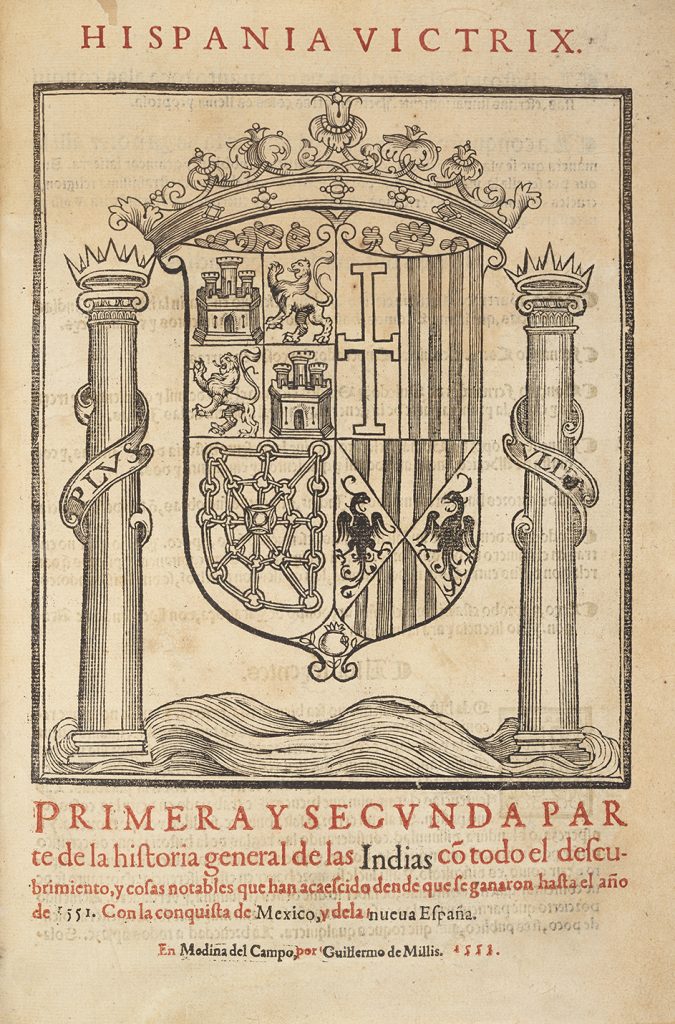

The Spanish crown also sought to control directly the writing of Spain’s history, including its exploits in the Americas. Chronicles required government approval for publication, and they could be banned entirely following publication if, upon further examination, they were judged to promote an unflattering image of Spain. Francisco López de Gómara’s Historia general first appeared in 1551 and went through nine editions before November 17, 1553, when Prince Philip ordered that all copies be collected and set a fine of 200,000 maravedis for anyone who dared to reprint. The chronicle’s account of the civil wars in Peru presented a particularly unfavorable view of Spanish conduct.

Somehow, the RBC’s copy of Gómara’s history survived that royal order (below left), and its title page has been given new life over 450 years later in the design of the Chronicles of Empire exhibition poster and flier (below right).

There are numerous other banned books to be seen in Chronicles of Empire, including famous chivalric romances and novels that Spain forbade to be exported to America. The Spanish crown feared that the indigenous population, whom they wished to educate and evangelize, would be unable to distinguish fiction from fact and would be confused by such literary works. Copies of the books found their way to the New World, nonetheless.

The exhibition Chronicles of Empire is part of the commemoration “One Hundred Years of Latin American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.” If you are unable to join us this evening, the exhibition is on view during regular Wilson hours through January 10, 2016.