In 1966, the City of Chapel Hill passed an ordinance (further amended in 1967) which stated, “it shall be unlawful for any person to consume or display beer, wine, whiskey or other alcoholic beverage in or on a street or sidewalk in Chapel Hill.”

This ordinance prompted the University to reconsider its own policies concerning alcohol. Administrators were especially concerned that alcohol would no longer be permitted during sporting events on campus. The Attorney General for North Carolina at the time, Thomas Wade Burton, stated that the ordinance could only limit the public drinking of beverages containing more that 14% of alcohol by volume, meaning that beer and wine were legally allowed to be consumed during sporting events.

For most of its history, the University relied on state and local laws to determine how alcohol was regulated on campus. However, the University was concerned that the new legislation was too broad in reference to where alcohol could be consumed. Dorm rooms were considered to be private residences, meaning that students over the age of twenty-one could legally store and consume beverages with more than 14% alcohol by volume in their dorm rooms. Students eighteen or older could consume beer, wine and other beverages containing less that 14% alcohol by volume anywhere on campus. This 14% rule caused the most problems for campus officials.

From 1966 to 1971 as laws changed and public debate continued. The University slowly tightened its own regulations over the consumption of alcohol. The Board of Trustees determined that it could no longer solely rely on state and local laws to regulate where students had access to and were allowed to consume alcoholic beverages. One of the main driving forces for the further restriction of alcohol on campus was pressure from the parents of students and alumni. They wanted no alcohol, regardless of strength, in residences. They also wished to further restrict what was allowed to be consumed during sporting events.

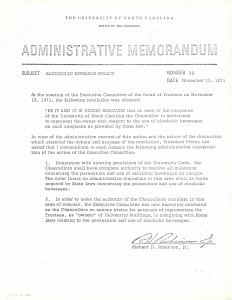

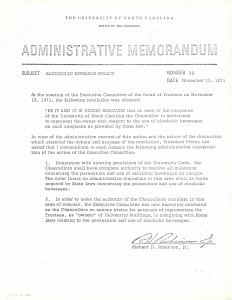

In 1971, a system-wide alcohol policy was instituted. It was not as restrictive as many parents were asking for, but it did close loopholes in the state laws concerning the 14% rule. The new policies, in being more restrictive than state law, also gave first right of discipline to the University. Thus a student who violated university rules would not also be in jeopardy of having to face punitive action from the state, unless the student also broke state laws. The new university policy followed state regulations for alcohol under 14% by volume. Over this limit, the Chancellor had complete discretion on where and when such alcohol could be consumed and it was not allowed in dorm rooms.

Similar discussions were taking place on other state university campuses during this period. In the lessening of restrictions on alcohol consumption other policies were being examined. In Georgia, female students over twenty-one, or sophomores and juniors with their parents’ permission, no longer had to obey a curfew. The policy that lifted this curfew also allowed women over twenty-one to drink off campus without facing a penalty from the University.