This year marks the close of the Sesquicentennial (150th) commemoration of the American Civil War, but it also marks the anniversary of the founding of many important institutions in the African American community, as many black churches trace their origins to this time around the end of the Civil War.

Prior to Emancipation, white southerners exerted control over African Americans in nearly every sphere of society, including religious worship. Slaves and free people of color were treated as second-class members of most churches, relegated to sitting in balconies or galleries of many churches, without much say in church affairs. Also, during slavery, many sermons were layered with messages emphasizing the obedience of slaves to their masters. But as freedom took hold for African Americans through Emancipation after the Civil War, many congregations began to split along racial lines and the institution of separate black churches emerged.

As a result of the Civil War, more than 300,000 formerly enslaved people in North Carolina —roughly a third of the state’s population—gained their freedom. Over 5,000 of these freedmen were in Orange County, with over 400 of these individuals in the town of Chapel Hill. There was great upheaval and movement as many of the newly free left their former masters and mistresses. Several first hand accounts of the war’s end describe an exodus of African Americans from the town. The same accounts indicate that some of those who left later returned.

Here in Chapel Hill, at least two historically African American churches were founded around the end of the war: St. Paul A.M.E. Church (founded in 1864) and First Baptist Church (1865).

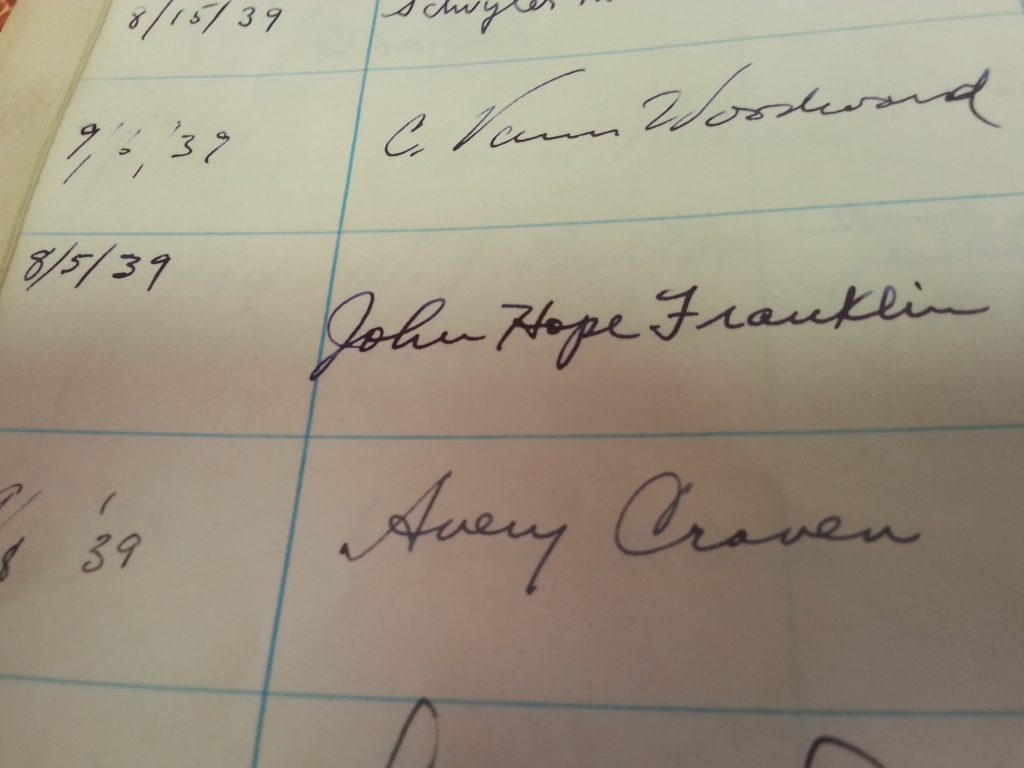

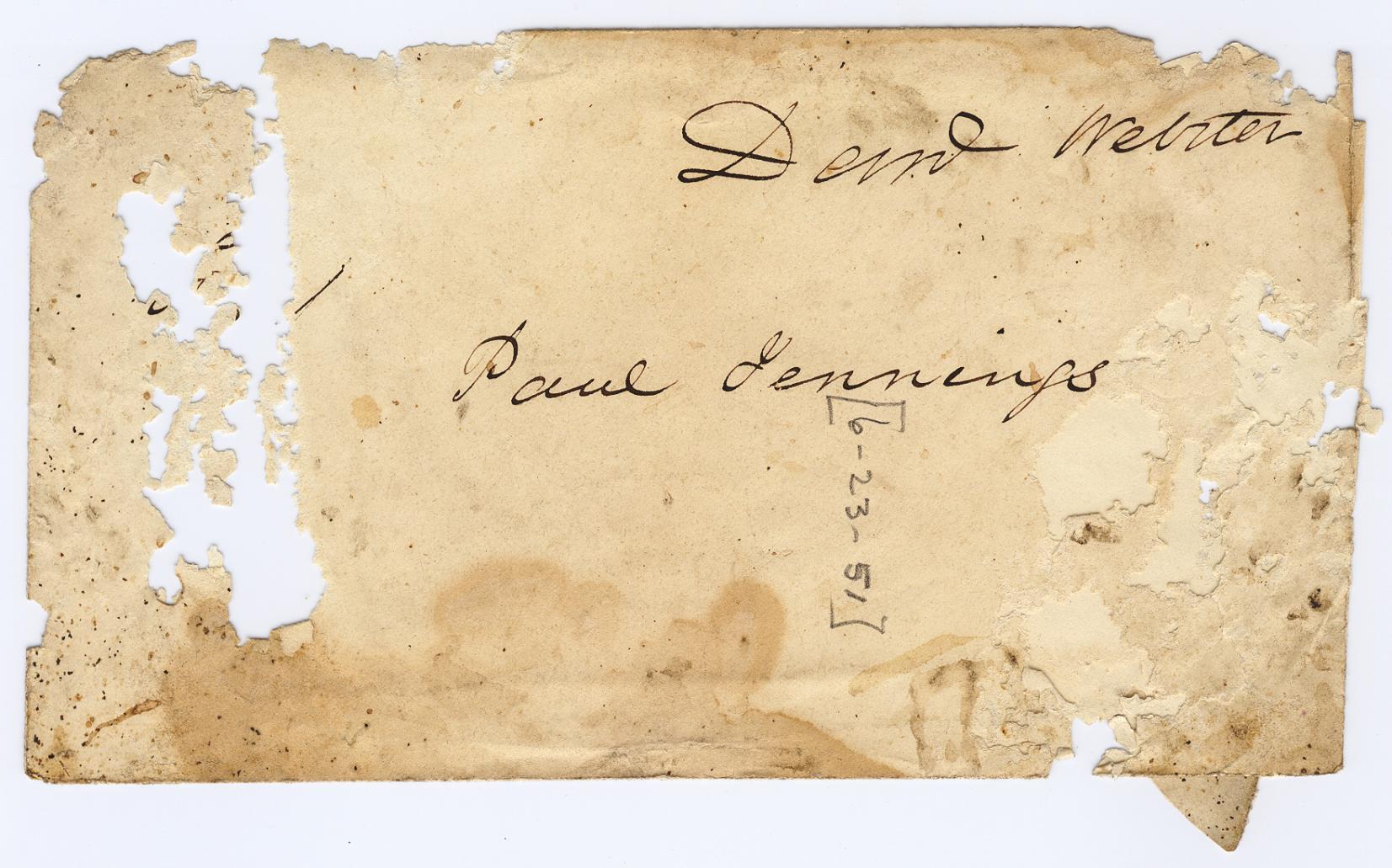

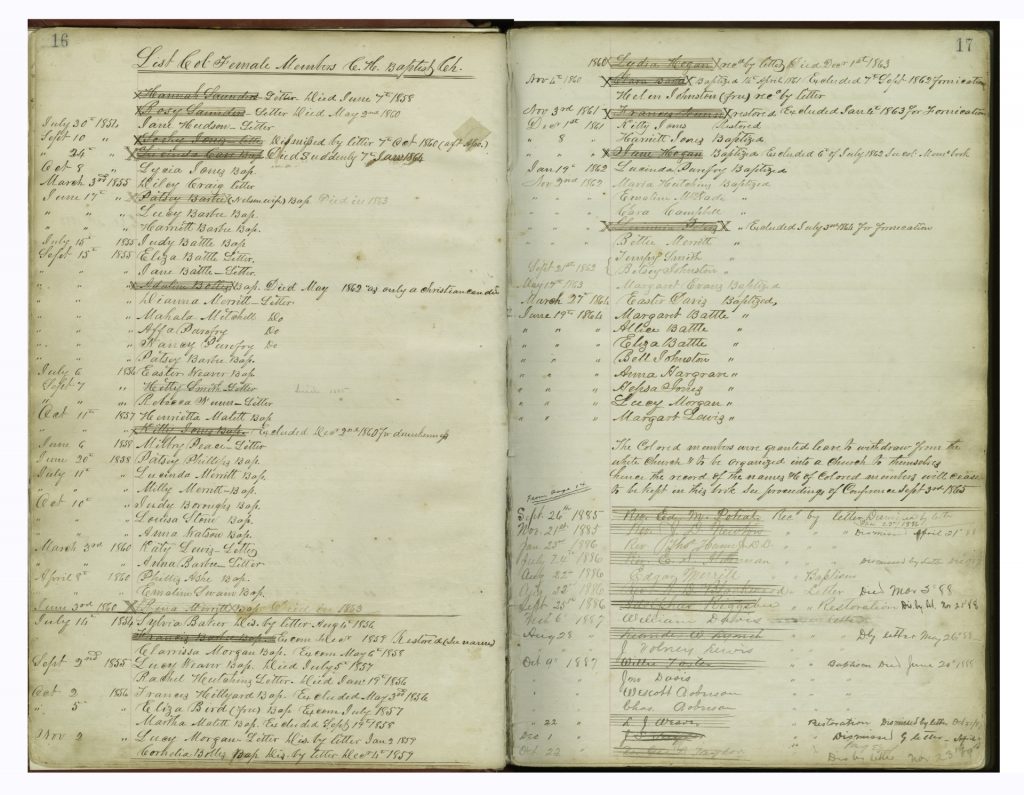

The Southern Historical Collection preserves an important piece of the story of the founding of First Baptist Church, within the minute books of the University Baptist Church. The congregation of the University Baptist Church (which was simply called the Baptist Church back then) included white members, enslaved men and women, and free people of color.

An entry in these minute books, dated September 3, 1865, states, “On motion it was unanimously voted that the colored patrons of this church be allowed to withdraw from the church and organize a church to themselves.” Several pages later in the minutes, it was also noted, “Four members have been dismissed by letter besides sixty-one colored members dismissed in September for the purpose of forming a separate church. This separate church, known as the Colored Baptist Church of Chapel Hill, is now in an acceptable operation and hopes are entertained of its doing well.”

The congregation of the new Colored Baptist Church initially met in an old schoolhouse on Franklin Street in Chapel Hill, known as the “Quaker Building,” until a church building could be built. Rev. Eddie H. Cole served as the church’s first pastor. The church changed names several times over the years, from Colored Baptist Church to First Baptist Church, then to Rock Hill Baptist Church and then back to First Baptist Church. This September will mark the 150th anniversary of the founding of First Baptist Church in Chapel Hill.