February 20, 1962 was an important day in United States space history. On that day, US Astronaut John Glenn became the first American to orbit the earth. On that same date thirty-six years earlier—February 20, 1926—an unsung hero of the United States space program was born in Richmond, Virginia.

On this February 20th, Morton collection volunteer and blog contributor Jack Hilliard takes a look at the life and times of that hero: Julian Scheer, who would have turned 88 today.

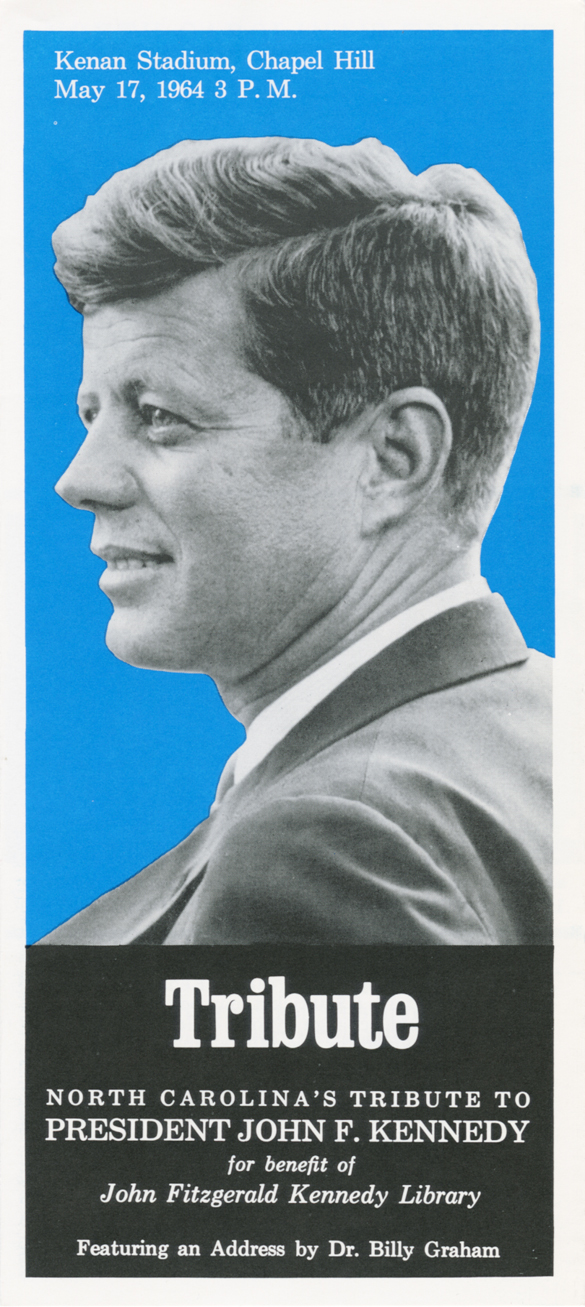

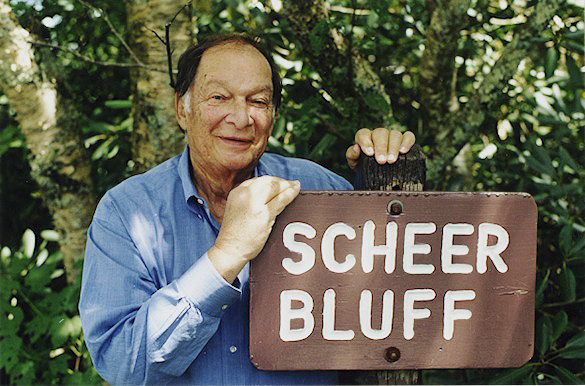

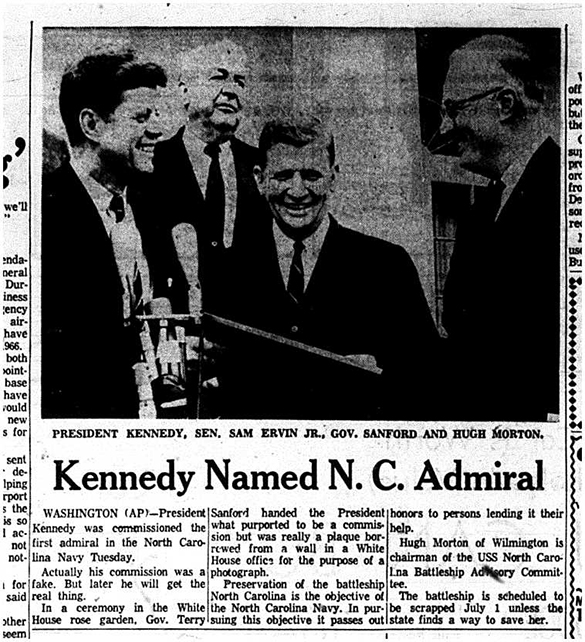

Julian Scheer posed next to the Scheer Bluff sign on Grandfather Mountain, date unknown. This scan of a portrait by Hugh Morton comes from a machine-made print in the Morton collection. The processing code on the back of the print includes the date 5 September 2001, just four days after Scheer’s death.)

The TV picture was slightly out of focus. It was black-and-white and the camera was tilted a little. By 2014′s standards of high tech, high definition television, it would likely be branded “NBQ”—not broadcast quality. Despite all of that, more than 700 million people around the world watched as US Astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the surface of the moon.

And we almost didn’t get to see it.

In the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) chain of command during the lead up to the launch of Apollo 11, the first trip to land a man on the surface of the moon, one man stood firm with his commitment that a TV camera would be part of the lunar luggage: Julian W. Scheer from Richmond, Virginia, a UNC Tar Heel, and a friend of Hugh Morton and family.

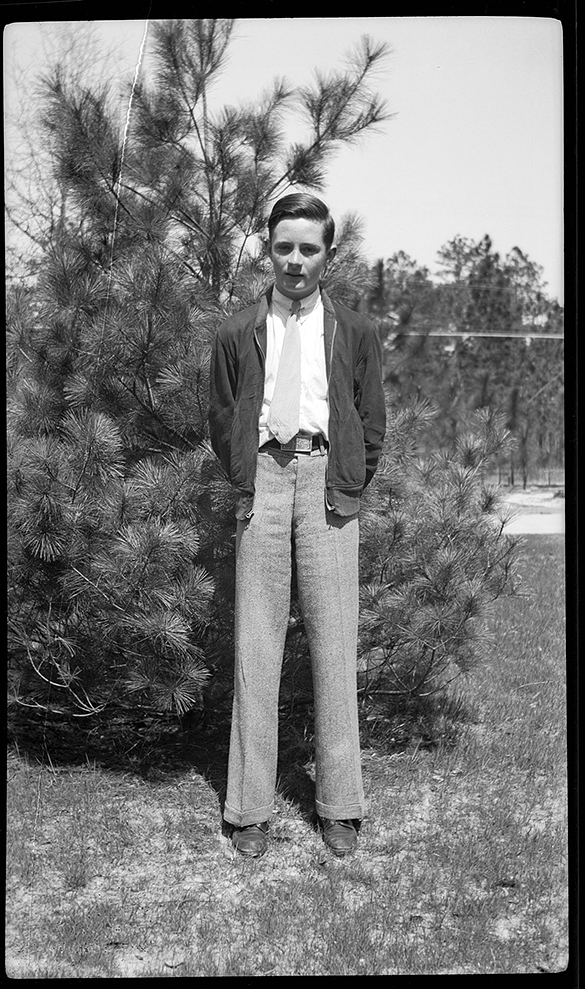

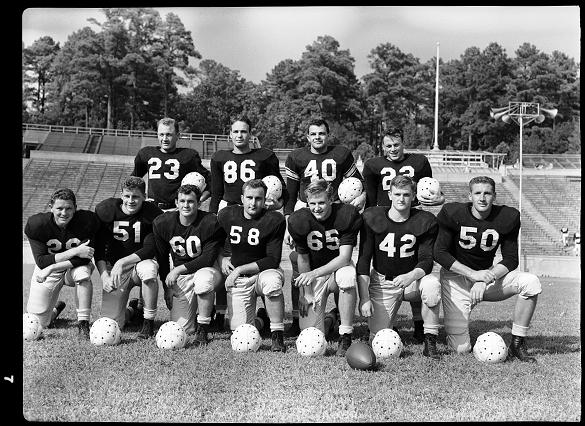

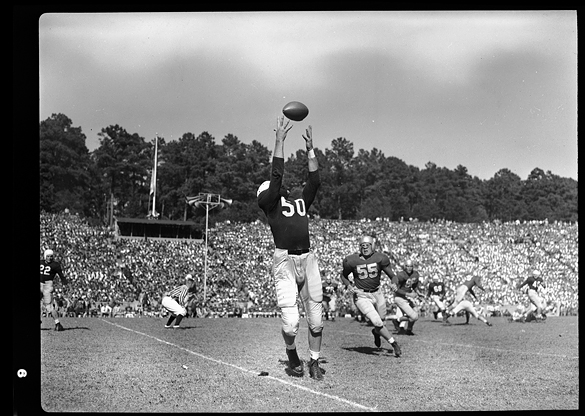

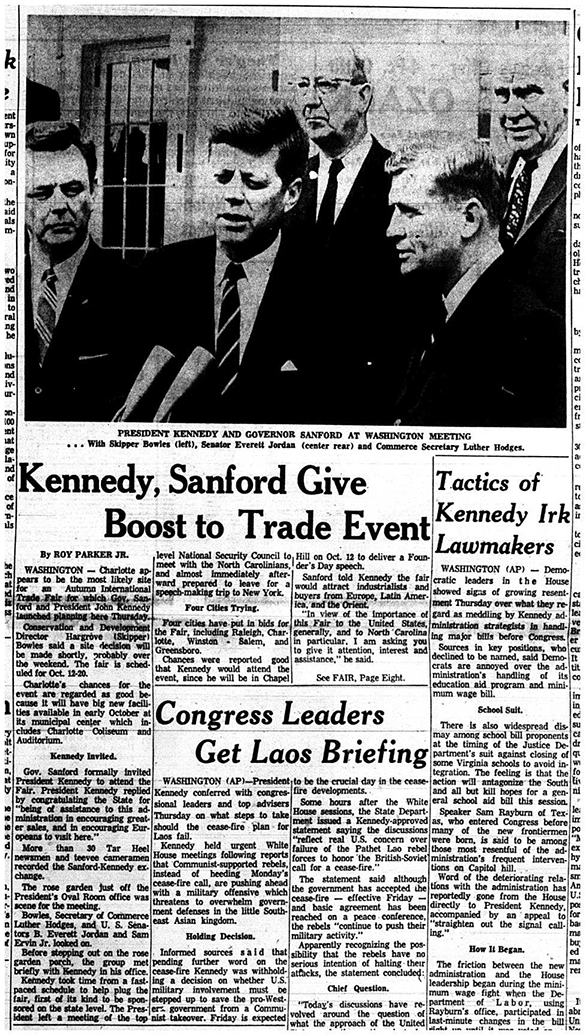

At age 17, Scheer joined the merchant marine and later served in the Naval Reserve. Following that World War II service, he enrolled at the University of North Carolina, graduating in 1950 with a degree in journalism and communications. He then became UNC Sports Information Director Jake Wade’s assistant, a position he held for three years, before joining The Charlotte News in 1953. (In 1956 another UNC Tar Heel joined the staff at The Charlotte News. His name: Charles Kuralt.)

During his early days in Charlotte, Scheer covered sports and news stories. In 1954 he went to the North Carolina coast, along with a group of other North Carolina reporters, to cover Hurricane Hazel. Also in that group was photographer Hugh Morton who, near the peak of the storm, took a picture of Scheer struggling against the rising water. The picture earned Morton a prestigious award. In the 1996 booklet, Sixty Years with a Camera, Morton described the circumstances on October 15, 1954:

During his early days in Charlotte, Scheer covered sports and news stories. In 1954 he went to the North Carolina coast, along with a group of other North Carolina reporters, to cover Hurricane Hazel. Also in that group was photographer Hugh Morton who, near the peak of the storm, took a picture of Scheer struggling against the rising water. The picture earned Morton a prestigious award. In the 1996 booklet, Sixty Years with a Camera, Morton described the circumstances on October 15, 1954:

Hazel was a very stormy thing. And when it came ashore at Carolina Beach, Julian Scheer and I were covering it for The Charlotte News. I asked Julian to walk through my picture, and the photo won first prize for spot news in the Southern Press Photographer of the Year competition.

That photograph is also on the front cover of the first edition of Jay Barnes’ 1995 book, North Carolina’s Hurricane History.

In 1956 Scheer received an invitation from an old college friend. Nelson Benton, who first worked at Charlotte radio station WSOC following his UNC graduation in 1949 and then joined WBTV Channel 3 News (also in Charlotte), asked Scheer if he would like to join a group that was going to visit Cape Canaveral, Florida. At that time, there was an Air Force base there and a few rockets had been tested, but very little news had come from the Cape. Scheer made the trip and was fascinated with what he saw and asked his editor at the “News” about a story of what was going on there. The editor didn’t show much interest, so Julian returned on his own time with his own money and did a series of stories.

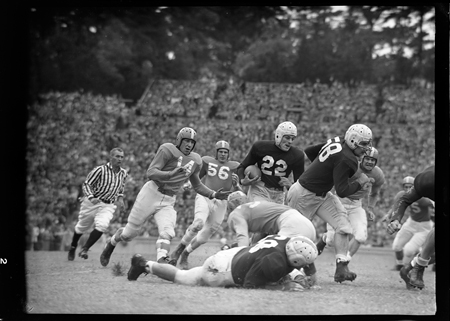

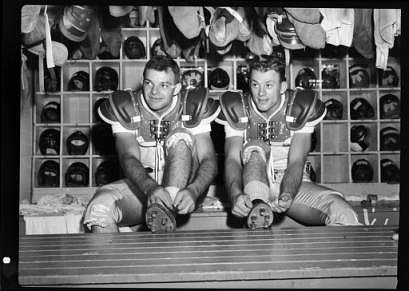

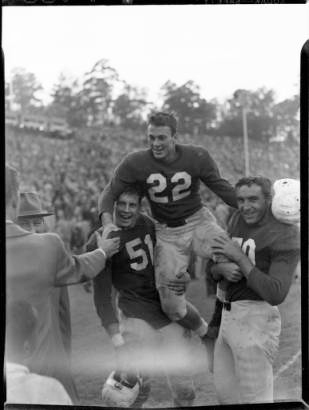

As the space race heated up and with the creation of NASA in 1958, more and more stories turned up in the papers and on TV. In 1959 Scheer wrote a book, along with NASA engineer Theodore Gordon titled First into Outer Space. The book was a best seller, but Scheer said the Pentagon took out some important content. (This was Julian Scheer’s third book. He teamed with Hugh Morton and Bob Quincy in 1958 for the Charlie Justice biography, “Choo Choo: The Charlie Justice Story.” That book was published by Orville Campbell in Chapel Hill. Also in ’58 he wrote Tweetsie, the Blue Ridge Stemwinder.)

Before he completed chapter one of his novel, he got a call from NASA administrator James Webb wanting him to come to Washington. Webb was very familiar with Scheer’s reporting on the US space program and wanted to hire him as his public affairs assistant. “We need your help,” said Webb. “I want you to write a plan for coordinating media coverage of the missions,” he added.

Scheer spent the next thirty days back in Charlotte formulating a grand plan that would shape the structure and policies of NASA into a team approach and would be responsible for getting the astronauts out of their flight suits and into the public consciousness. Scheer never lost sight of the importance of the fact that media includes both broadcast and print.

He sent the plan to Webb and was soon called back to Washington. When he walked in the door, Webb said, “I accept your offer to go to work for me.” Both men laughed, before Scheer finally said yes. “I want you to run this program just as you’ve outlined it. You’ll work directly for me,” said Webb.

Julian Scheer outside NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., September 1965. (This is a slightly different pose than the image in online collection. Photograph cropped by the editor.)

Scheer arrived back at Cape Canaveral just in time for the final mission of Project Mercury, astronaut Gordon Cooper’s two-day stay in orbit in May 1963. Cooper would be the final US astronaut to go into space alone, because Project Gemini was next and would consist of ten successful two-man flights starting in March 1965 and continuing until November 1966. Project Apollo and the moon would be next.

On Friday, January 27, 1967 the Apollo One crew, consisting of Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee, was training at the Cape for the first Apollo launch when tragedy struck. A spark ignited a fire in the spacecraft, killing all three astronauts. Scheer was faced with a media crisis. To his credit, he withheld information until all the families involved were properly notified.

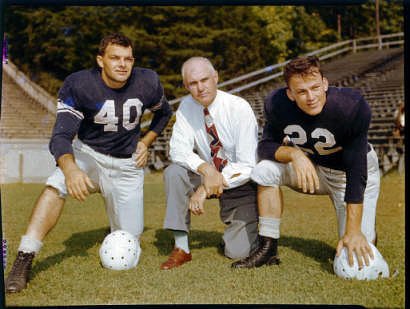

Twenty-one months would pass before Apollo would actually fly. On October 11, 1968 US Astronaut Wally Schirra checked out a new system in Apollo 7. The US space program was back on track and headed for the moon. Apollo 8 flew around the moon on Christmas Eve 1968. Who could forget Commander Frank Borman and crew reading from the Bible on that cold December night on live television? In an interview after the Apollo program, Commander Borman would say, “the (Apollo) program was really a battle of the cold war and Julian Scheer was one of its generals.”

Apollo 9 in March of ‘69 and Apollo 10 in May were the dress rehearsals for the moon landing which would be next.

The blueprint for Apollo 11 has Julian Scheer’s fingerprints all over it. He was responsible for naming the Apollo 11 command module “Columbia.” He participated in discussions over whether the astronauts would place a US flag on the moon and he helped determine the wording on the lunar module plaque that reads in part, “We came in Peace for All Mankind.” But perhaps his biggest achievement was his fight with NASA engineers to get a television camera on board the lunar lander “Eagle.” Weight was a critical issue for “Eagle” and the engineers said a TV camera would just be extra weight. Said Scheer, “You’re going to have to take something else off. The camera is going to be on the spacecraft.” And so it was.

Wednesday, July 16, 1969 began at 4 AM for about 150 CBS News personnel at Cape Canaveral. Preparations were underway for the launch of Apollo 11. Two hours later, at 6 AM (EDT) came this:

“This is a CBS News Special Report, ‘Man on the Moon: The Epic Journey of Apollo 11.’”

It was the voice of CBS legendary announcer Harry Kramer in New York. Anchors Walter Cronkite and Wally Schirra were on the air three hours and thirty-two minutes before the launch at the cape. The countdown went well as about 3,500 news personnel watched from the Complex 39 press site at Cape Kennedy (now it’s the Kennedy Space Center). Among them was Hugh Morton. (According to the Morton collection finding aid, however, only seven 35mm slides are extant.)

An estimated half million space watchers lined the surrounding Florida beach areas.

Then at 9:32 AM (EDT) the mighty Saturn V (five) rocket, powered by 7,500,000 pounds of thrust, carrying Neil Armstrong, “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins began a slow climb to the moon.

As Cronkite watched on his TV monitor, he jubilantly cried out,

Oh boy, oh boy, it looks good Wally . . . What a moment! Man on the way to the moon!

Most of the CBS launch team then headed back to New York to get ready for the biggest show of all on Sunday, July 20, 1969.

As CBS signed on at 11:00 AM (EDT) on the 20th, the first voice we heard was that of Charles Kuralt, Julian Scheer’s co-worker at The Charlotte News in 1956:

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. Some five billion years ago, whirling and condensing in the darkness, was a cloud of inter-stellar hydrogen, four hundred degrees below zero, eight million miles from end to end. This was our solar system waiting to be born.

Kuralt had recorded his essay days before because on this day he would fly across the United States, stopping along the way getting people’s thoughts on this historic day. His program would be called A Day in the Life of the United States, and would air on September 8, 1970.

Then, Cronkite and Schirra and about 1,000 CBS News team members began a “32-hour day” live from Studio 41 in New York. Among those team members was Julian Scheer’s old college buddy Nelson Benton, who was stationed at Bethpage Long Island at the Grumman Corporation where a full scale model of the Lunar Module was set up. Benton worked with Engineer Scott MacLeod who had tested the module.

During the next five hours, Cronkite and Schirra were at the center of a media frenzy as they introduced feature segments, interviewed space experts, and tossed to CBS News Correspondents around the world.

At 4:08 PM (EDT) the astronauts were given a final “go” for the flight down to the surface of the moon. It took nine minutes and forty-two seconds. Then came Armstrong’s famous words, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” Cronkite sat speechless, glasses in hand, shaking his head from side to side. Schirra wiped a tear from his eye.

In six hours, thirty-eight minutes, and thirty-eight seconds, a 38-year-old American astronaut from Wapakoneta, Ohio would set foot on the surface of the moon.

At 10:25 PM (EDT), Cronkite held up a copy of Monday’s New York Times with the banner headline “Men Land on the Moon.” Never before had the Times printed a headline in such large type. Then came this exchange between Houston and Neil Armstrong:

Armstrong: “Okay Houston, I’m on the porch!”

Houston: “Man, we’re getting a picture on the TV, we see you coming down the ladder now.”

Cronkite: “Boy! Look at those pictures.”

Armstrong: “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

It was 10:56:20 PM (EDT) on Sunday, July 20, 1969.

Cronkite: “Isn’t this something! 238,000 miles out there on the moon, and we’re seeing this.”

Schirra: Oh, thank you television for letting us watch this one!”

Schirra could have said . . . perhaps should have said (in my opinion): “Thank you Julian Scheer for letting us watch this one!”

Following the Apollo 11 crew’s return safely to earth on July 24, 1969 after eight days, three hours and eighteen minutes, Julian Scheer was awarded NASA’s highest recognition, the Distinguished Service Medal. He then led the crew in exploiting its public relations potential. He orchestrated and led round the world tours. In a 1999 USA Today article, Scheer said, “The Apollo mission was the chance to show off U.S. technological superiority. Clearly the Russians were going to the moon. We were head-to-head. We emphasized that.”

Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon, said, “He (Scheer) understood the needs of the media and also the needs of the flight crews. He was, in many cases, able to accommodate both.”

Following a successful Apollo 12 mission, Scheer was faced with another crisis during the flight of Apollo 13. Two days into its flight an oxygen tank exploded crippling the service and command modules. The lunar landing was cancelled, and for the next six days there was wall-to-wall media coverage until the crew landed safely on April 17, 1970.

When Apollo 14 launched on January 31, 1971, Hugh Morton along with wife Julia and daughter Catherine, were guests of Julian Scheer at the Cape. This mission saw astronaut Alan Shepard, America’s first man in space, return to space and land on the moon.

As it turned out, Apollo 14 was Julian Scheer’s final flight at NASA. Two days after his 45th birthday, on February 22, 1971, he left NASA and would become campaign manager for Terry Sanford’s 1972 run for the presidency. Scheer remained a consultant to the space program in Washington and was a trustee of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum.

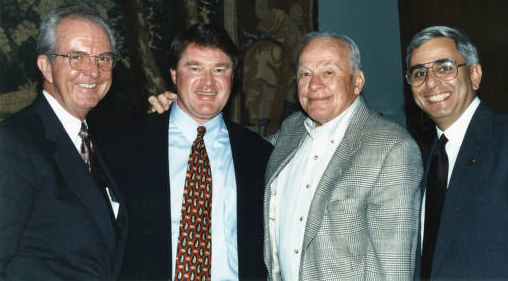

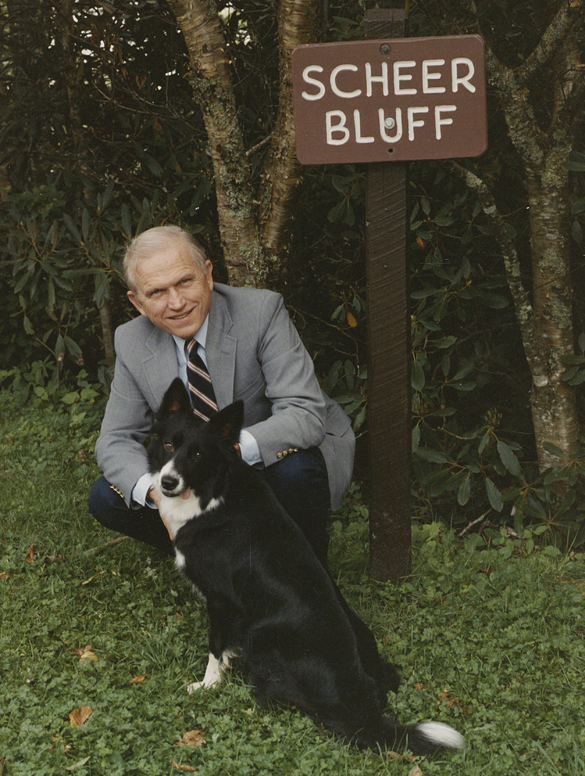

Group portrait of Cape Hatteras Lighthouse committee members, possibly outside the Carolina Club on the UNC campus. Left to right: Jim Heavner (CEO, The Village Companies of Chapel Hill and broadcaster); James G. (Jim) Babb (Executive VP, Jefferson Pilot Communications); Dr. William Friday (UNC President); unknown; unknown; Julian Scheer; and Hugh Morton.

Julian Scheer and Hugh Morton crossed paths again in 1981 when Morton formed the “Save the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Committee,” in response to the growing concerns about the safety of the 129-year-old structure. The committee read like a who’s who in North Carolina and brought together some of the best public relations/media minds in the world. And of course Julian Scheer, with more experience with government agencies than anyone else Morton knew, topped the list. The committee offered an alternative to moving the lighthouse as the US Corp of Engineers wanted to do. But Morton’s committee wasn’t able to keep the landmark in its seaside location.

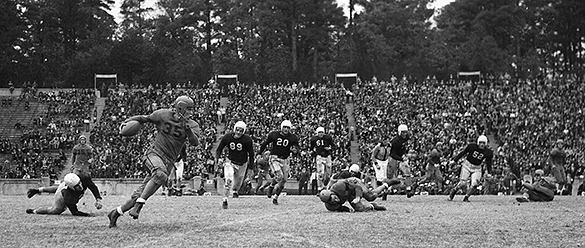

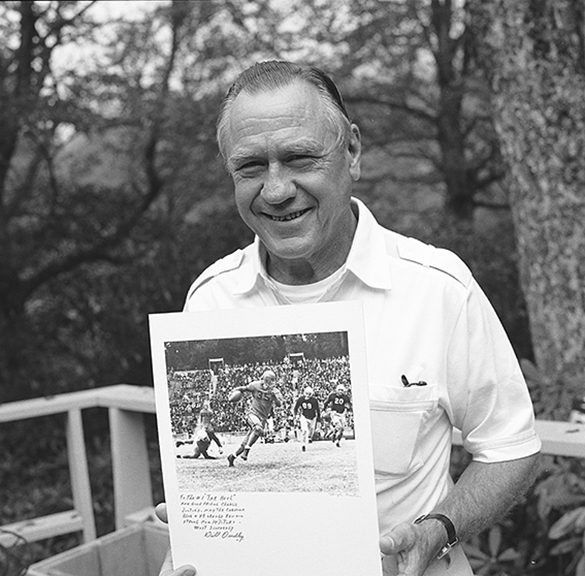

On April 30, 1984, UNC’s great All-America legend Charlie Justice was the subject of a charity roast in Charlotte for the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation. Scheer wasn’t able to attend the event in person, but he sent an audio tape poking fun at his dear friend. The audience loved it when Scheer said he and co-author Bob Quincy would have to answer “for all the lies we told” in that 1958 Charlie Justice biography.

In an interview in 2000, Julian Scheer said, “in my mind . . . I was always writing. It never left me. I always got a charge out of seeing my byline in the paper . . . .” Also that year Scheer wrote two children’s books, A Thanksgiving Turkey and Light of the Captured Moon. He had previously written two other children’s books: Rain Makes Applesauce (1965) and Upside Down Day (1968).

The tragic news from Catlett, Virginia on Saturday, September 1, 2001 was that Julian Scheer had died in a tractor accident at his home. He was 75-years-old. The world will forever remember “the small step and giant leap” made by Neil Armstrong 238,000 miles away on Tranquility Base at 11:56:20 PM (EDT) on July 20, 1969; and the award-winning reporting by Walter Cronkite and Wally Schirra to millions of viewers watching CBS-TV; but neither of these historic events would have captured the imagination of the world without that seven-pound TV camera and the strong will of Julian Weisel Scheer, a true unsung hero of Project Apollo and the American space program.

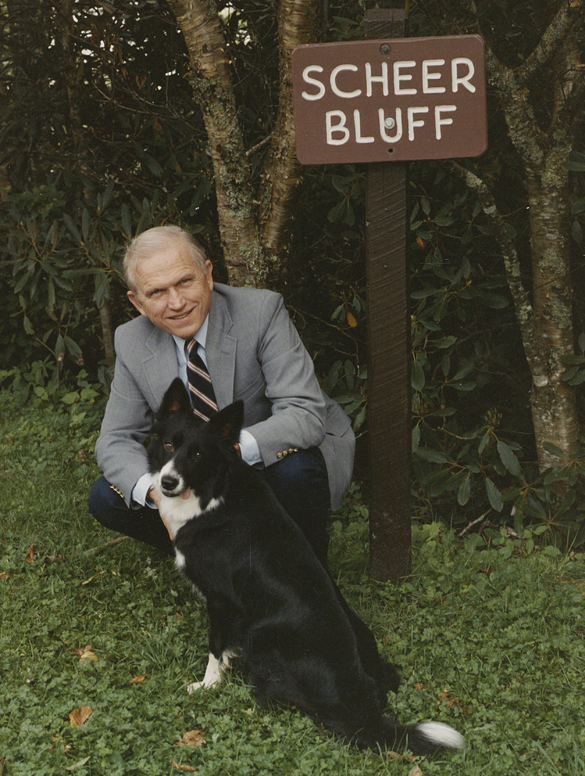

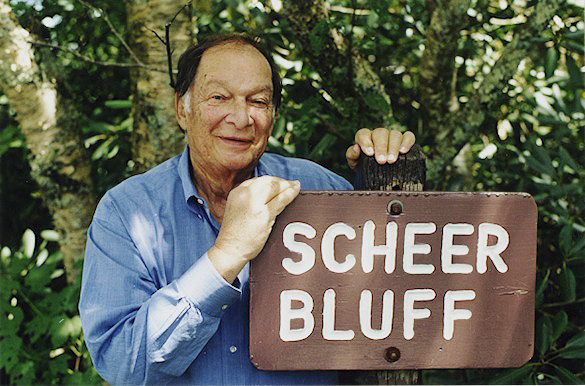

Frank Borman at Scheer Bluff, Grandfather Mountain. Scanned from a print that’s not included in the online collection (cropped by editor).

An Epilogue:

In the early 1960s Hugh Morton paid tribute to his dear friend Julian Scheer by naming a nice overlook at the 5,000 foot level at Grandfather Mountain, “Scheer Bluff.” The Scheer family would often visit Grandfather Mountain and in the early 1980s, to his surprise, Scheer received a photograph of astronaut Frank Borman standing at the “Scheer Bluff” sign. Said Borman, “Julian, this is the first time I’ve called your bluff. We’ve been through a lot together and I’ve always valued your advice . . . many years of happiness to a true friend.”

If you check the dictionary for the word “bluff,” you’ll find this definition among others: “rough and blunt, but not unkind in manner.”

Correction: March 14, 2014: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the CBS announcer. It is Harry Kramer, not Ted Cramer. Kramer’s name is misspelled in a 1968 phone roster.