On this day twelve years ago, the state of North Carolina lost a treasure—and Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard and his wife Marla lost a dear friend. Sarah Alice Hunter Justice passed away in Shelby, North Carolina at age 79. Today, Jack Hilliard takes a look at the life and times of a very special lady.

She was an angel here on earth, the epitome of a lady, always a gleam in her eye, and she never raised her voice. —Jane Browne, Justice family friend, 2/18/04

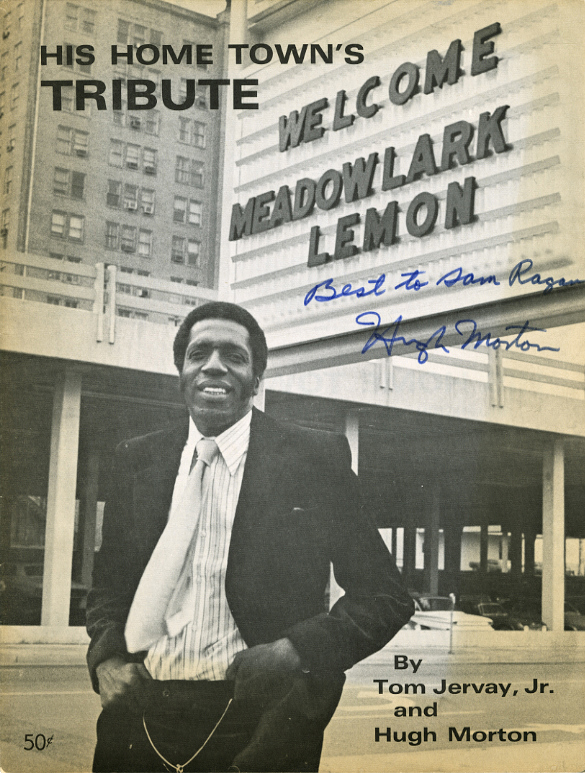

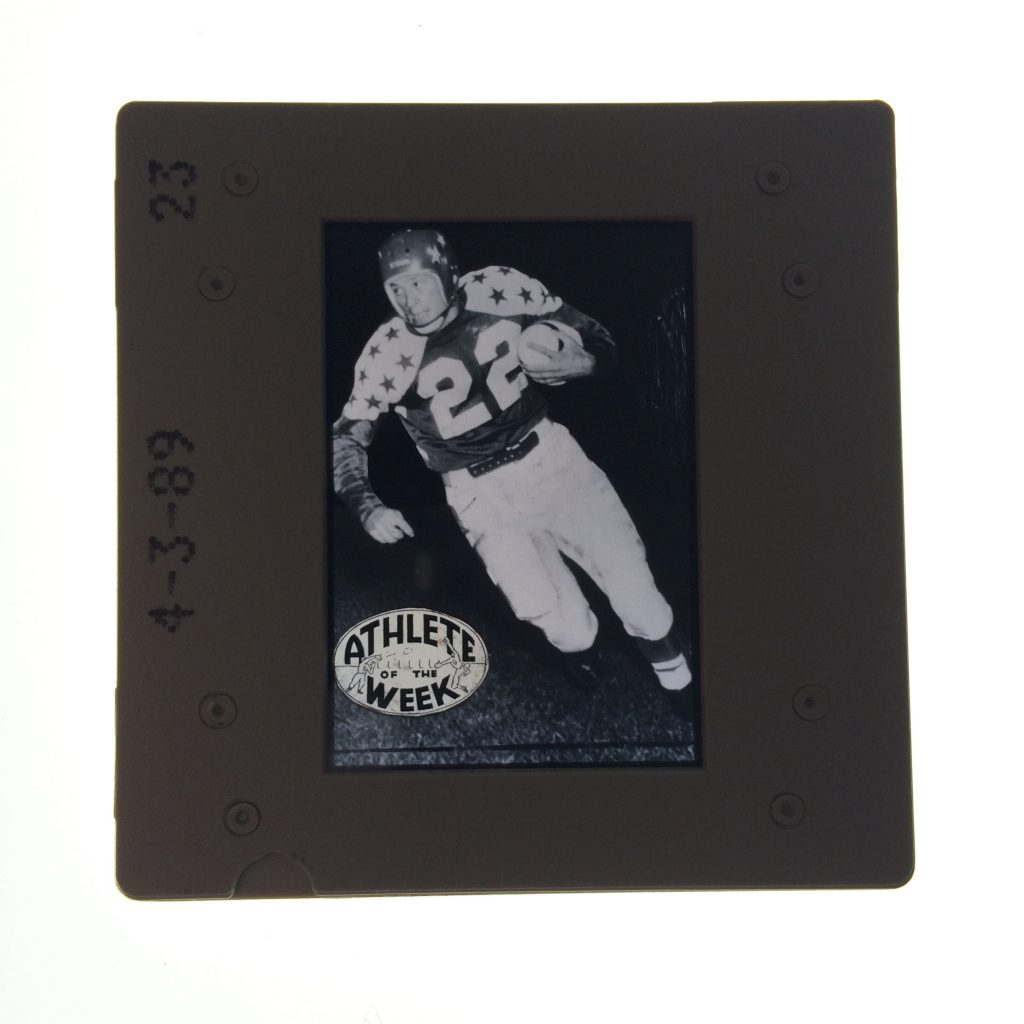

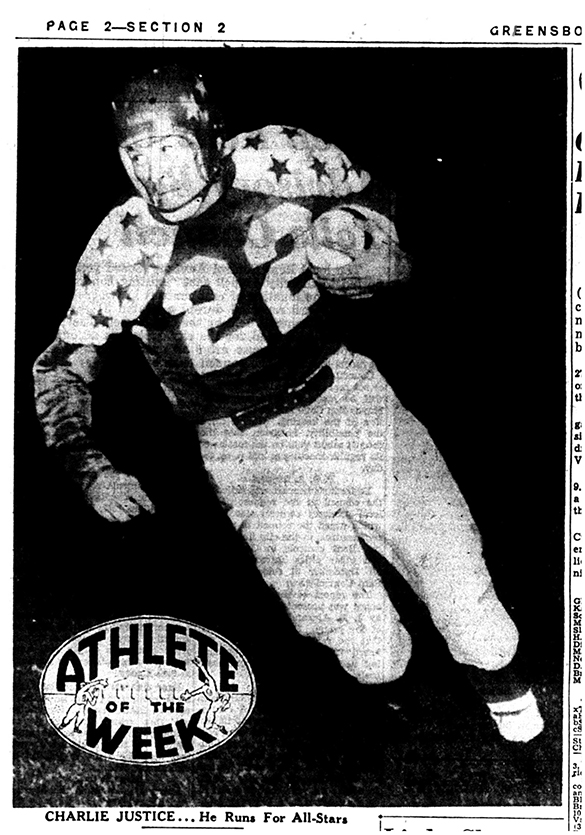

It was early in the spring term, 1942, at Lee H. Edwards High in Asheville. Football star Charlie Justice knew he was going to be late for class, so he applied some of his football skills and began to run down the hall. In the process he ran over Sarah Alice Hunter. She laughed and didn’t make anything of it. Charlie was impressed, and later asked her out. A notation in the campus newspaper’s “Rumors Afloat” column on March 20th said, “Charlie looks like he’s finally settled down to one girl—Nice going Sarah.”

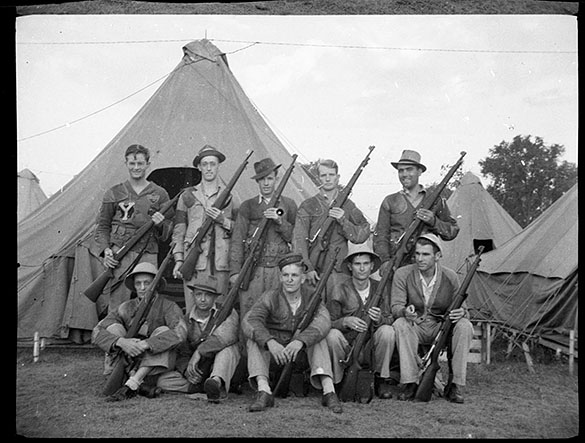

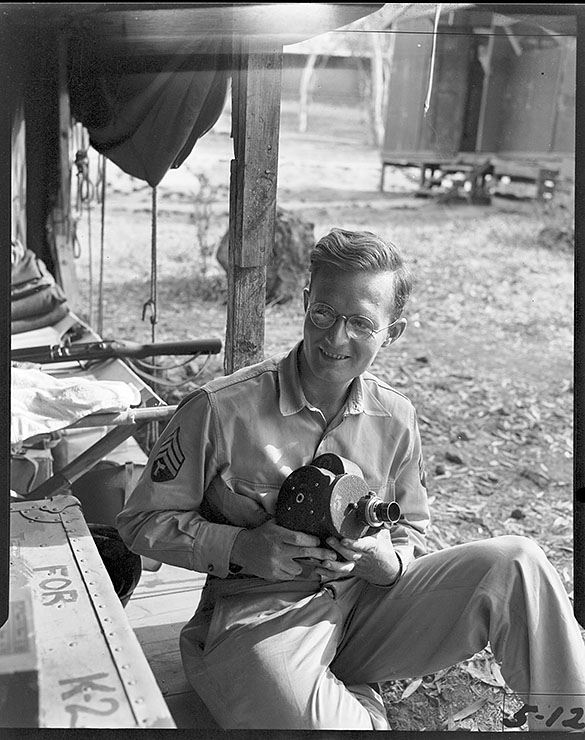

Following her graduation in May 1942, Sarah headed to Appalachian State in Boone, but decided to return home to Asheville at Christmas. Charlie finished at Lee Edwards on May 28, 1943, and was off to the Navy at Bainbridge Naval Training Station in Bainbridge, Maryland. He continued playing football, while Sarah took a job with the Naval Observatory in nearby Washington, D. C.

Ten days after Charlie led Bainbridge to a 46 to 0 win over the University of Maryland, he went on a well deserved leave. At the same time, Sarah took a brief leave from her job. The two headed to Asheville, where they were married at Trinity Episcopal Church on November 23, 1943.

Following his military obligation, Charlie and Sarah moved back to North Carolina and enrolled at UNC on Valentine’s Day, 1946. Since Charlie was eligible for the GI Bill, Sarah got his football scholarship, thus becoming the first female to attend Carolina on a football scholarship. In Chapel Hill, Charlie’s football heroics became legendary and on football Saturdays Sarah was always in the stands, cheering him on wearing her special good luck hat. On August 23, 1948, the Justice family increased by one with the birth of son Charles Ronald. (They called him Ronnie.)

Following his playing days at Carolina, Charlie signed on with the Washington Redskins for four seasons. In 1952, daughter Barbara joined the family and they returned to North Carolina in 1955, where they were often Hugh Morton’s guests at events in Wilmington and Grandfather Mountain. They especially liked the Highland Games and Gathering of the Scottish Clans each July.

Over the years, Charlie and Sarah offered their name, their time, their talent, and their money to just about every cause in the Tar Heel state from Chapel Hill to Asheville to Greensboro . . . from Hendersonville to Flat Rock and Cherryville. They were there when needed. Sarah gave much of her time to the causes that improve the lives of the mentally challenged. In Cherryville, she helped raise funds for Gaston Residential Services, which provides housing for the handicapped. The Special Olympics program was also close to her heart. In 1989, when the Charlotte Treatment Center named a wing of its facility for Charlie, they also named a wing of the facility for Sarah.

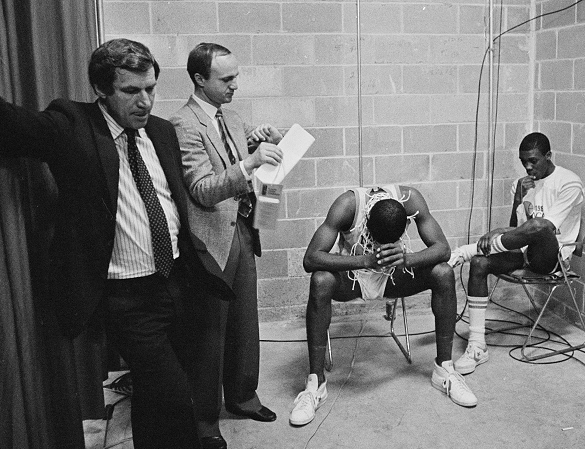

On June 11, 1993, Charlie and Sarah lost their son Ronnie…the victim of a heart attack. He was 44 years old. Following Carolina’s win over Duke 38 to 24 on November 26, 1993, a special celebration was held in the Carolina Inn on the UNC campus. While the win was celebrated, the real reason for the celebration was to offer sincere congratulations to Charlie and Sarah Justice on their 50th wedding anniversary, which was actually on November 23rd but game day three days later gave everybody a good reason for a celebration. The invitation for the event set the stage for the event:

A Golden Anniversary

Should be shared with family and friends.

Please join Billy, Barbara, Emilie

And Sarah Crews, Leah, David

And Beth Overman and in spirit

And loving memory Ronnie Justice,

In celebration of the fifty year

Marriage of Sarah and Charlie Justice.

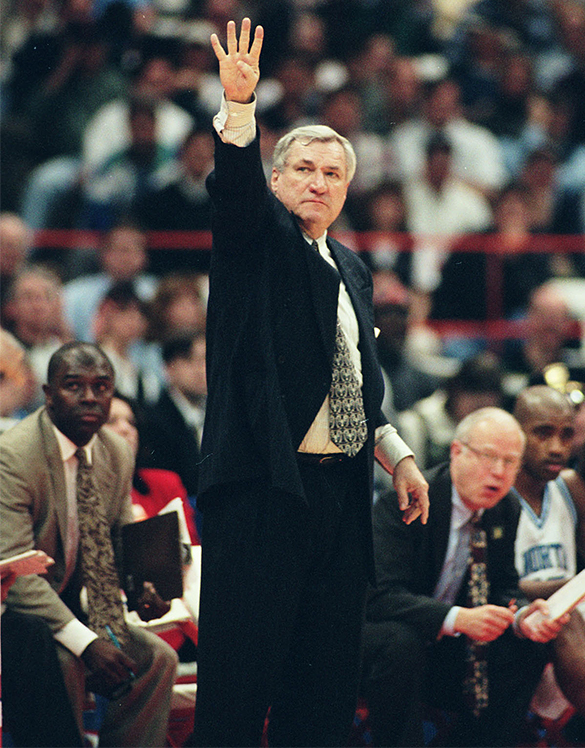

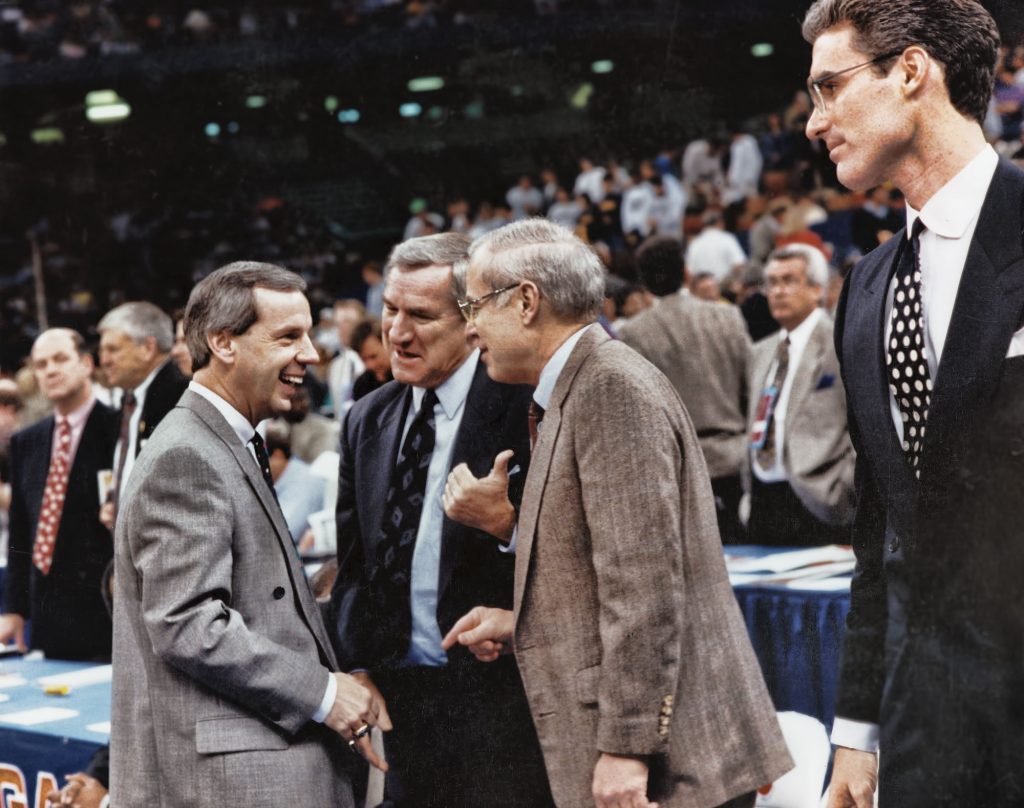

There were family members, teammates, friends, and fans in attendance. Following a family toast by Barbara, Tar Heel Head Football Coach Mack Brown offered congratulations and spoke about the importance of Carolina’s football heritage. And throughout the ceremony, Hugh Morton was there with camera in hand documenting every phase of the event.

You didn’t need to be around Charlie Justice very long before it became very clear that his asking Sarah to marry him was the most important event in his life. Although she was often thought of as Charlie’s wife, Sarah Justice didn’t fit the old saying, “Behind every great man stands a great woman . . . .” Charlie and Sarah stood side by side . . . they were a team. They were connected. Their love story was the stuff of storybooks. Sarah was always there . . . but chose to be just outside the spotlight.

In a 1995 interview with Justice Biographer Bob Terrell, Charlie talked about how the “Hand of Providence” placed him at the right place at the right time: “If I hadn’t knocked Sarah Hunter down while scuffling in the hall in high school, she might never have noticed me. You bet that was providential!”

Soon after the Terrell biography was published in early 1996, Charlie began a seven-year battle with Alzheimer’s—a battle he would lose at 3:25 AM on Friday, October 17, 2003. A memorial service celebrating his life was held at The Cathedral of All Souls in the Biltmore section of Asheville on Monday, October 20th. Asheville Citizen-Times senior writer Keith Jarrett beautifully described the scene outside the church following the ceremony.

“It was one of several warm, touching scenes on a beautiful, cloud-free day with a sky the color of you know what. Sarah sat in a wheelchair just outside the Cathedral as the UNC Clef Hangers, an all-male a cappella group, softly sang James Taylor’s ballad ‘Carolina in My Mind.’ Sarah tilted her head and was just inches away from the singers. For a brief moment she closed her eyes, soaking in the words and perhaps recalling the memories of a marriage of love and devotion of 60 years.”

On November 4, 2003, I received a note from Barbara Crews: “Mother and I are at the beach. Mom loves the ocean. I think she has such peace now, she feels her job is done, and she did it well. . . . She is the best person I have ever known.”

There was a message on my answering machine when I arrived home from work on Monday, February 9, 2004. It was from Billy Crews telling me that his mother-in-law had passed away earlier that day. It had been 115 days since Charlie died. Marla and I had visited Sarah two days before on Saturday, February 7th at Hospice at Wendover in Shelby. Sarah Justice was 79-years-old.

In an article in The Charlotte Observer issue of Wednesday, February 18, 2004 titled “Caregiver more than Mrs. Choo Choo,” Gerry Hostetler talked with some of Sarah’s family. Son-in-law Billy Crews said, “She was always full of grace, and for her whole life a caregiver. She enjoyed doing things for other people and being out of the limelight.” Granddaughter and namesake Sarah Fowler added, “She was a very giving person who always put others’ needs in front of her own. She was the backbone of this family and kept us going.”

Finally, Barbara ended the interviews with this: “She was just a saint, the kind of person you want to be around.”