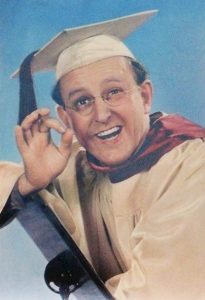

On October 5, the city of Rocky Mount installed an historical marker honoring James Kern “Kay” Kyser (1905-1985). Kyser was a native of Rocky Mount and a 1928 graduate of UNC-Chapel Hill. While at UNC, Kyser majored in commerce and was active in numerous extracurricular activities, including acting as head cheerleader for the Tar Heels and leading a band.

Kyser became a bandleader when Hal Kemp, another UNC student, turned his popular band over to Kyser when he left the university to further his career. When Kyser later turned professional in the 1930s, he and his band became internationally famous.

Wilson Special Collections Library holds Kyser’s papers and several objects that belonged to him. Gallery staff worked with a researcher to select items for use in exhibits marking the historical marker celebration. Such sessions are always an opportunity for us to learn more about our holdings. Not only do we review the information we have about the items, we usually learn something from discussions with the visitor. No exception this time.

Perhaps the most interesting of the holdings is a graduation cap, hood, and gown worn by Kyser in his role as the “Ol’ Perfessor of Swing.” Kyser developed an act combining a quiz with music called Kay Kyser’s Kollege of Musical Knowledge.

Another interesting artifact in this collection is an old Italian mandolin. We don’t know its connection to Kyser. The instrument was popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and possibly Kyser was a member of one of many “mandolin orchestras” that formed then. This mandolin—erroneously described as a lute in our information system and now corrected—is of the bowlback or “potato bug” variety. The current form was developed largely by the Gibson Guitar Corp., and this type was made famous by bluegrass musicians such as Bill Monroe.

A few Kyser-related items from our collection are currently on view in Rocky Mount at the Imperial Centre for the Arts and Sciences and Braswell Memorial Library. Other Kyser-related artifacts are available upon request in the North Carolina Collection Gallery.