We’d heard recently that North Carolina produced more sweet potatoes than any other state. The North Carolina Sweet Potato Commission is justly proud (see their website to join the NC Sweet Potato recipe club). This had us wondering whether there were other crops and agricultural products in which North Carolina led the nation. We checked the website for the National Agriculture Statistics Service and found that, as of 2001, we ranked first in turkeys and tobacco. North Carolina was second in hog production (behind Iowa), and a distant third in strawberries (behind California and Florida).

Category: Tar Heelia

Egg Nog

This holiday season, don’t settle for store-bought egg nog. Make your own, the way they used to in eighteenth-century North Carolina. We found this recipe in William Attmore’s Journal of a Tour to North Carolina, 1787 (James Sprunt Historical Publications vol. 17 no. 2., 1922, pp. 42-43):

Tuesday, December 25. This Morning according to North Carolina custom we had before Breakfast, a drink of EGG NOG, this compound is made in the following manner: In two clean Quart Bowls, were divided the Yolks and whites of five Eggs, the yolks & whites separated, the Yolks beat up with a Spoon, and mixt up with brown Sugar, the whites were whisk’d into Froth by a Straw Whisk till the Straw wou’d stand upright in it; when duly beat, the Yolks were put to the Froth; again beat a long time; then half a pint of Rum pour’d slowly into the mixture, the whole kept stirring the whole time till well incorporated.

December 18, 1776: North Carolina Constitution

This Month in North Carolina History

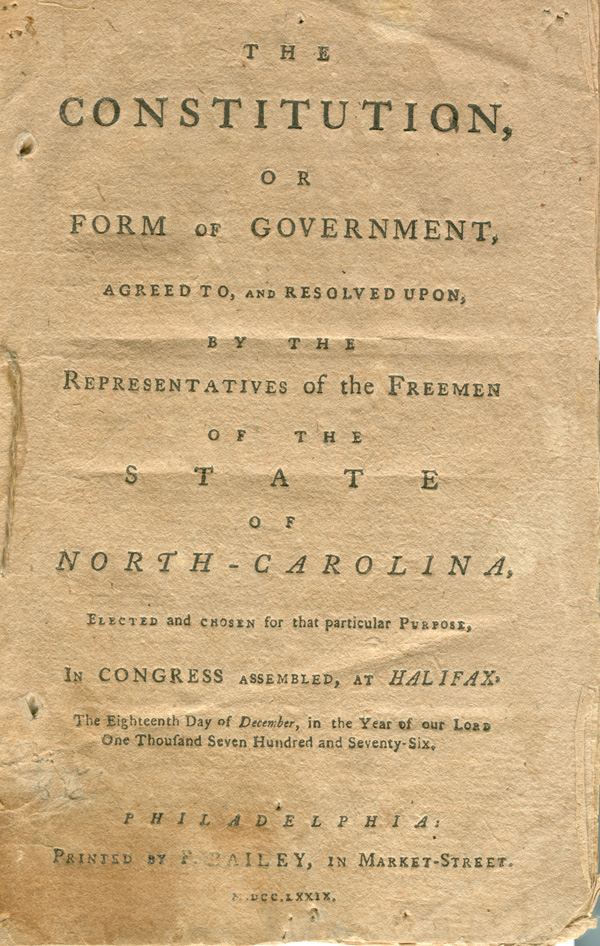

News that the American colonies had declared independence from Great Britain finally reached North Carolina on July 22, 1776. One of the first orders of business in the newly independent state was the writing of a constitution. Elections for the Provincial Congress were held in October and, once elected, the representatives met in Halifax. Several states had already adopted constitutions, and North Carolina looked to these as examples. The legislators also examined the English Declaration of Rights and wrote to John Adams for advice. Rather than go through the lengthy and uncertain process of submitting the document to the voters, the representatives agreed that once they approved the final draft, it would be enacted. On December 18, 1776, North Carolina had its first constitution.

News that the American colonies had declared independence from Great Britain finally reached North Carolina on July 22, 1776. One of the first orders of business in the newly independent state was the writing of a constitution. Elections for the Provincial Congress were held in October and, once elected, the representatives met in Halifax. Several states had already adopted constitutions, and North Carolina looked to these as examples. The legislators also examined the English Declaration of Rights and wrote to John Adams for advice. Rather than go through the lengthy and uncertain process of submitting the document to the voters, the representatives agreed that once they approved the final draft, it would be enacted. On December 18, 1776, North Carolina had its first constitution.

The 1776 North Carolina Constitution has many elements that will seem familiar to North Carolinians today. The Constitution opens with a Declaration of Rights, containing twenty-five guarantees of personal freedom that anticipate the Bill of Rights in the United States Constitution and many of which are present in similar form in the current state constitution. The first North Carolina constitution also presents a familiar form of government, with a governor and a bicameral legislature.

However, there are several sections that differ significantly from current practice. The most notable of these were the property requirements for officeholders and voters. In order to be eligible for the Senate, members had to own at least three hundred acres of land in the county they sought to represent; candidates for the House of Commons were required to own one hundred acres; and voters were required to own at least fifty acres to be eligible to cast a ballot for a senator.

Under the 1776 constitution, most of the power was vested in the General Assembly. Governors were chosen by the legislature, served only a one-year term, and were not eligible to serve more than three terms in a six year period. Legislators were appointed by county (with a few assigned to specific towns), without regard to population. This vested a disproportionate amount of influence in the eastern part of the state, which had many small counties, even though the western counties began to increase steadily in population.

The 1776 constitution was effective in establishing an independent government in North Carolina and guaranteeing individual liberties for its citizens. Yet under this document, the state remained in the control of a small group of primarily eastern elites. North Carolina grew slowly, on its way to earning the nickname “The Rip Van Winkle State” in the early nineteenth century. By overlooking many of the demands of its less prosperous citizens, North Carolina saw a widespread emigration and was finally forced to draft a more egalitarian constitution. The state passed a series of amendments in 1835 that changed to a system of representation that was determined by population and allowed for the popular election of the governor. It was not until after the Civil War, in 1868, when North Carolina finally adopted a constitution that did not include property requirements for officeholders.

Sources:

William S. Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

John L. Sanders, “A Brief History of the Constitutions of North Carolina.” In North Carolina Government 1585-1979: A Narrative and Statistical History. Raleigh: North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State, 1981.

“Constitution of North Carolina: 18 December 1776.” Avalon Project, Yale Law School, http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/states/nc07.htm

Image Source:

The Constitution, or Form of Government, Agreed to, and Resolved Upon, by the Representatives of the Freemen of the State of North Carolina. Philadelphia: Printed by F. Bailey, 1779.

Movers and Shakers

Recent editions of the Polk City Directory include a “Movers & Shakers Section.” We’re guessing that this section was compiled to appeal to marketers trying to reach people described by the publisher as “the most affluent individuals, professionals, business owners and key executives within the community.” Since librarians are, typically, neither affluent nor would we be described as “key executives,” we were surprised to find a few of our colleagues listed as Movers & Shakers. We always knew how important our work was, but it’s nice to see it confirmed in print.

Are you a “Mover & Shaker”? Polk City Directories are available for most larger towns and cities in North Carolina. Stop by your local library or contact us at the North Carolina Collection to see if there’s a directory for your community.

November 1979: Greensboro Killings

This Month in North Carolina History

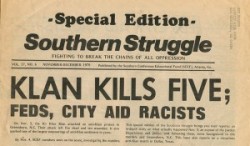

On November 3, 1979, members of the Communist Workers Party (known then as the Worker’s Viewpoint Organization) sponsored a rally at Morningside Homes, a housing project in Greensboro. Billed Klan Kills Five Headlineas a “Death to the Klan Rally,” the demonstrators gathered to speak out against what they saw as continued racial injustice in North Carolina.

A group of self-proclaimed Klansmen and Nazis attended the rally and fired upon the crowd, killing five people and wounding nine. Much of the violence was captured on film by reporters who were covering the event.

The men accused of firing on the crowd were apprehended and charged with murder. In November 1980 a jury found them not guilty on the grounds of self-defense. After extensive FBI inquiries into the killings, the case was reopened and, in 1983, nine people were indicted for conspiracy to violate the protesters’ civil rights. Again, the defendants were acquitted.

In addition to their outrage at the violence in their community, many people in Greensboro blamed the police department for failing to act promptly enough to prevent the killings. The frustration in the community continued to grow as the courts failed to convict anyone for the shootings.

At the twentieth anniversary of the killings in 1999, it was clear that tensions in Greensboro still ran high and that there were many unresolved feelings and accusations surrounding the case. A Truth & Reconciliation Commission, modeled on similar projects in South Africa, was established in 2004. The Commission began holding public hearings on the 1979 killings, operating under the principle that the community cannot begin to heal until the events of the past are honestly and openly confronted. The final report of the Commission is due in 2006.

Sources

Elizabeth Wheaton, Codename GREENKIL: The 1979 Greensboro Killings. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987.

“The Third of November.” Southern Exposure, vol. 9 no. 3 (Fall 1981), pp. 55-67.

Greensboro Truth & Reconciliation Commission

http://www.greensborotrc.org/

Greensboro Truth & Community Reconciliation Project

http://www.gtcrp.org/ (available via the Wayback Machine)

Image Source:

Southern Struggle (Special Edition), vol. 37 no. 6 (November-December 1979). Greensboro Massacre Materials, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“They Died Fighting Rather Than Live As Slaves.” Card produced by the Committee to Avenge the Greensboro-CWP 5, [1979]. Greensboro Massacre Materials, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

State Songs

All true Tar Heels know that our state song is William Gaston’s “The Old North State,” adopted as the official song by the state legislature in 1927.

So we were surprised to see another song staking the claim. Bettie Freshwater Pool’s Literature in the Albemarle (published by Ms. Pool in Elizabeth City, 1915) includes the poem “Carolina,” labeled as “(State Song).” It begins:

I love thee Carolina!

Broad thy rivers, bright and clear;

Majestic are thy mountains;

Dense thy forests, dark and drear;

Grows the pine tree, tall and stately;

Weeps the willow, drooping low;

Bloom the eglantine and jasmine;

Nods the daisy, white as snow.

Then the chorus:

Let me live in Carolina

Till life’s toil and strife are past!

Let me sleep in Carolina

When my sun shall set at last!

Where the mocking bird is singing–

Where my heart is fondly clinging.

I would sleep when life is o’er

Sweetly on the old home shore.

The closing lines proclaim that the “Brightest star of all the Union / Is the glorious Old North State.” Perhaps this was an unofficial state anthem before Gaston’s got the nod? We think the only way to settle this is with a head-to-head matchup, just like on American Idol. Let the people decide.

October 1864: Rose O’Neal Greenhow

This Month in North Carolina History

At dawn on the first of October 1864 the body of Rose O’Neal Greenhow washed ashore in the surf near Fort Fisher in North Carolina. Perhaps the most famous spy of the Confederate States of America had died as dramatically as she lived.

Rose was born in 1813 or 1814 into a planter family in Maryland. Her father, John O’Neal, was murdered by one of his slaves in 1817. His widow, Eliza O’Neal, was left with four daughters and a cash-poor farm to manage. In part to help family finances, Rose was sent, in her mid-teens, to Washington, D. C. along with her sister Ellen to live with their aunt, Maria Ann Hill. Mrs. Hill and her husband managed a highly regarded boarding house across from the U. S. Capitol. The house was often referred to as the “Old Brick Capitol” since it originally had been built as the temporary meeting place of Congress after the Capitol had been burned in the War of 1812. Pretty, lively, and intelligent, Rose was popular with the members of Congress who boarded with her aunt, and she had several suitors. In 1835 she married Robert Greenhow, a wealthy bachelor who had trained as a physician but ultimately became an official in the United States Department of State. In addition to bearing a large family, Rose became an important figure in Washington society. She was charming, witty, politically astute, and a fervent champion of the southern states in the increasingly bitter sectional struggles of the 1840s and 1850s. The death of Robert Greenhow in 1854 left Rose financially stretched, but she continued her association with important national political figures, particularly President James Buchanan. Rose considered the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 to be a national disaster and whole-heartedly supported secession and the newly formed Confederacy.

Sometime in 1861 Rose Greenhow was recruited as a spy for the Confederacy. She quickly formed a network of agents from among her Washington circle of Confederate sympathizers and began enthusiastically and efficiently gathering information about the Union Army camped around the capital, which she transmitted to General P. G. T. Beauregard who commanded Confederate forces in nearby Virginia. Rose charmed information from important beaureaucrats, army officers, and politicians including, it was rumored, a Republican senator who sent her passionate love letters. She gave Beauregard the date on which the Union Army would began its advance on his position in 1861 and was credited by him with an important contribution to the subsequent victory at the battle of Manassas. Rose refused, however, to become the stereotypical spy who blends in with her background to escape detection. She continued vigorously to defend the southern cause and lambast Republicans. After Manassas she began to come under suspicion. She was arrested in August of 1861 and held for the next year and nine months without being charged or brought to trial. Rose was hardly a model prisoner, reviling her guards, complaining about her treatment and generally making herself a thorn in the side of the Lincoln government. At the end of May 1863 she was exiled to the Confederacy.

Rose Greenhow was given a heroine’s welcome in Richmond and thanked personally by President Jefferson Davis for her aid to the Confederacy. Davis also took the unprecedented step of asking Rose to promote Southern interests in England and France as his personal, if unofficial, representative. In August 1863 Rose and her youngest daughter, also named Rose, sailed on a blockade runner from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Bermuda where she booked passage to England. Rose was warmly greeted by many in the English aristocracy who sympathized with her and her cause. Over the next year she spoke with a number of leaders of British politics and society including Thomas Carlyle and Lord Palmerston. She was granted an audience by Napoleon III of France and visited with southerners who had taken up residence abroad. A British publishing house brought out her memoir, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolitionist Rule at Washington, which was a success.

In August 1864 Rose returned to America, convinced that she could do nothing to persuade the British or French governments to recognize the Confederacy. On the last night of September her ship, the blockade runner Condor approached the mouth of the Cape Fear River on the run to Wilmington. It was spotted by a U. S. naval vessel early on the morning of October 1st and ran aground trying to escape. Rose was carrying dispatches for President Davis and her book profits in gold coins in a leather bag around her neck. She demanded that the captain set her ashore immediately, although he tried to convince her that the ship was safe under the guns of Fort Fisher until she floated off the shoal. In the end Rose had her way and with several other people was launched in a boat for the shore which was only a few hunded yards away. Within minutes the small boat capsized. Rose sank out of sight immediately while the others clung to the overturned boat and ultimately survived. Her body was buried in Wilmington, North Carolina.

Sources

Blackman, Ann. Wild Rose: Rose O’Neale Greenhow, Civil War Spy. New York: Random House, 2005.

Ross, Ishbel. Rebel Rose: Life of Rose O’Neal Greenhow, Confederate Spy. New York: Harper, 1954

Greenhow, Rose O’Neal. My Imprisonment and the first year of Abolition Rule at Washington. London: R. Bentley, 1863.

Image Source:

“Mrs. Greenhow and the Two Other Passengers Demanded to be Set Ashore.”

Half-tone plate engraved by C.E. Hart from a drawing by Stanley M. Arthurs.

In Harper’s Monthly Magazine, March 1912, p. 575.

Cackalacky

Even though we pride ourselves on our knowledge of the history and culture of “North Cackalacky,” when it comes to this unusual nickname, we’re absolutely stumped. We’d heard the name for years, and it seems to be pretty widespread, be we can’t figure out where in the world it came from. We tried the usual authorities – Norman Eliason’s Tarheel Talk (UNC Press, 1956), and the comprehensive Dictionary of American Regional English (Harvard University Press, 1985-) – but with no luck.

The folks at Cackalacky Hot Sauce (note the nice photograph from the North Carolina Collection on their home page) are on the hunt as well. They’ve brought new attention to the name, but so far haven’t been able to dig up anything authoritative on its origin. If you have suggestions or ideas about how we came to be “Noth Cackalacky,” we’d love to hear them.

September 1802: Spaight-Stanly Duel

This Month in North Carolina History

In the early nineteenth century, North Carolina men from all walks of life often resorted to violence to settle quarrels and arguments. For those near the lower end of the social scale this usually meant fists and bad language. For those who considered themselves gentlemen, it often meant a duel. Preceded by a formal exchange of challenge and response, a duel with swords or pistols continued until the offended party declared that honor had been satisfied or until one of the combatants was wounded or killed. In September, 1802, North Carolinians were shocked by a fatal duel involving two of the state’s leading citizens.

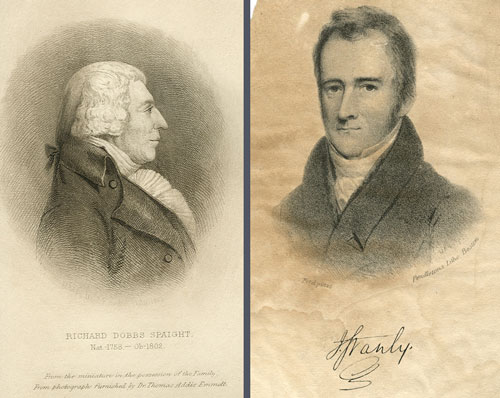

Richard Dobbs Spaight, by the age of 44, had had a distinguished career in North Carolina politics. Spaight had fought for the patriot cause in the Revolution under General Caswell, served several terms in the North Carolina House of Commons, represented North Carolina in both the Continental Congress and the United States Congress, and been elected the first native-born governor of the state. Spaight’s opponent in the duel, John Stanly, was 28 in 1802, but had already followed a Princeton education with service in the North Carolina General Assembly. In 1802 he was the United States Congressional Representative from the district once served by Spaight. Both men lived in New Bern and were members of the Jeffersonian Republican Party.

Trouble began when friends advised Spaight that Stanly had raised questions about Spaight’s allegiance to the Republican Party. An angered Spaight demanded that Stanly “…give me that satisfaction which one gentleman has a right to demand of another.” Several more letters were exchanged between the two men which appeared to settle the matter, and Stanly gave Spaight permission to clear the air by publishing their correspondence. In forwarding their letters to the New Bern Gazette, however, Spaight added several remarks which Stanly found offensive. This led to an increasingly heated exchange in the newspaper and finished with Stanly distributing a handbill in which he accused Spaight of wishing to “strut the bravo” with remarks which showed a “malicious, low and unmanly spirit.” In reply, Spaight published a flyer accusing Stanly of being “a liar and scoundrel.” Stanly challenged Spaight and the two men and their seconds met at 5:30 on the afternoon of September 5th behind the Masonic Hall in New Bern. Standing opposite each other, armed with pistols, the two men exchanged fire three times with no damage except a tear in Stanly’s coat. On the fourth exchange Spaight was hit in the side. He died the next day.

There was general shock and outrage in the state over the loss of so distinguished a leader as Richard Dobbs Spaight. Stanly defended himself eloquently in a letter to Governor Benjamin Williams who issued a pardon absolving him from legal guilt. The General Assembly, however, passed on November 5, 1802, a bill entitled “An Act to Prevent the Vile Practice of Dueling Within This State.” The new law provided that anyone who participated in a duel would be heavily fined and barred from any office of trust or profit in state service. If an individual were the survivor of a duel to the death, he and any who assisted him would hang “without benefit of clergy.”

The act of 1802 put North Carolina on record as opposing dueling, but it did not stop the practice completely. For one thing, the act only applied to duels within the state. North Carolinians could cross the border into either South Carolina or Virginia where the practice was tolerated. The prohibition against dueling itself was often ignored by those who respected the old custom more than the new law. Gradually, however, dueling became less common until it disappeared in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Sources:

Wellman, Manly Wade, “The Vile Practice of Dueling: John Stanly and Richard Dobbs Spaight. New Bern, 1802,” The New East, 4:5 (October, 1976): 9-11, 45-46.

Johnson, Guion Griffis. Antebellum North Carolina: a social history. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1937.

August 16, 1918: Rescue at Sea

This Month in North Carolina History

The Atlantic waters off the Outer Banks of North Carolina are infamous for shipwrecks. More than six hundred vessels have been lost in this “Graveyard of the Atlantic” to a combination of strong currents, dangerous shoals, and sudden storms. In wartime, particularly during the twentiety century, human malice exceeded even natural catastrophe as a destroyer of ships and sailors.

In both World War I and World War II German submarines found the vicinity of the banks a rich hunting ground and almost 100 ships were lost. Through the first half of the nineteenth century aid to ships and seamen wrecked on the Outer Banks came from local people acting as the need arose. In 1789 the Federal government assumed responsibility for the construction of a string of lighthouses along the North Carolina coast from Cape Hatteras to Cape Fear.

In addition to the lighthouses, seven lifesaving stations were constructed along the coast from Currituck Beach in the north to Little Kinnakeet in the south. At each location a station keeper and at least six surfmen remained ready around the clock to go to the aid of ships in distress. The lifesaving crews operated from the beach piloting heavy lifeboats through the surf and out to stricken vessels to save passengers and crew.

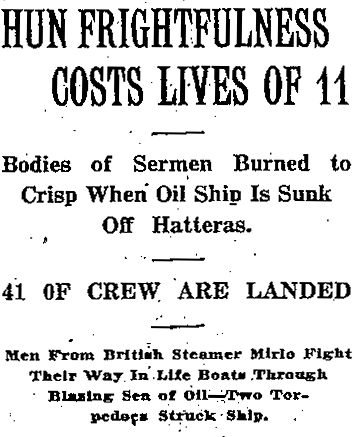

Of the many daring rescues attempted by the Lifesaving Service one of the most famous involved the sinking of the British tanker Mirlo on August 16, 1918, off of the shores of Bodie Island. The Mirlo was working its way up the North Carolina coast bound for Norfolk with a load of gasoline from New Orleans. She safely passed Cape Hatteras and was near Wimble Shoals off Bodie Island when she struck a mine layed by the German submarine U-117.

The resulting explosion was seen by Captain John Allen Midgett and the crew of the Chicamacomico Lifesaving Station. Midgett and his men launched their power lifeboat through the surf into a rising wind and made for the Mirlo. Two boats had been launched successfully from the ship, but a third had capsized and remained floating upside down near the Mirlo with a number of desperate sailors clinging to the keel as burning gasoline from the sinking ship spread steadily nearer.

Captain Midgett found a narrow lane in the flaming sea and guided his boat along it until it reached the overturned craft. The sailors were taken safely aboard, and the Chicamacomico lifeboat moved out of the burning gasoline, located the other two boats and brought all three to safety on the beach. For their courageous action and superb seamanship, Captain Midgett and his crew were awarded Gold Lifesaving Medals of Honor from the United States and Victory Medals from the government of Great Britain. Later the men of the Chicamacomico Station received Grand Crosses of the American Cross of honor from the United States Coast Guard.

The Lifesaving Stations were abandoned by the Coast Guard after World War II in favor of more modern and sophisticated tools and methods of aiding ships in distress. The Chicamacomico Station, however, has been carefully restored and stands as a monument to the brave surfmen of the Lifesaving Service.

Sources:

Mobley, Joe A. Ship Ashore! The U.S. Lifesavers of Coastal North Carolina. Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, 1994.

Stick, David. Graveyard of the Atlantic: shipwrecks or the North Carolina coast. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1952.