We are pleased to announce a new research fellowship for undergraduate students who are interested in getting hands-on experience with archival research and who want to contribute to the ongoing conversation about UNC history.

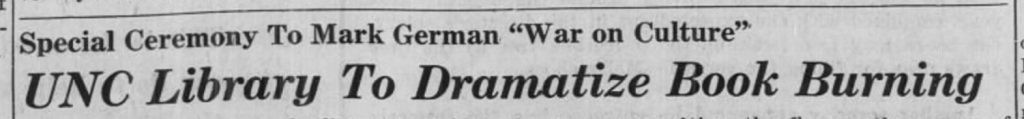

The University Library and the Chancellor’s Task Force on UNC-Chapel Hill’s History are sponsoring four undergraduate research fellowships for summer 2017. The fellows will work in the University Archives in Wilson Library on research projects that will help to expand the existing narrative of UNC history. The research will focus on underrepresented, excluded, or misrepresented people and events – the “untold” stories that have not made it into traditional accounts of Carolina’s history.

How to Apply

The Carolina’s Untold History fellowships will be administered through the Office of Undergraduate Research as part of the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) program. Visit the SURF website for more information about how to apply. http://our.unc.edu/students/funding-opportunities/surf/

Research Topics

As part of the application process, students will work with a faculty adviser and with the staff of the UNC University Archives to develop a research topic. Topics will be related to UNC history and must focus on aspects of university history that have not been covered at length in existing histories of UNC. University Archives staff can help applicants determine whether there are sufficient archival resources to support the nine-week fellowship. Students should contact the University Archives to discuss potential topics: archives@unc.edu.

Sample Topics

The following are just examples of the types of topics students might choose to explore.

Applicants are encouraged to be thoughtful and creative about their research topics and should contact the University Archives to discuss potential research ideas.

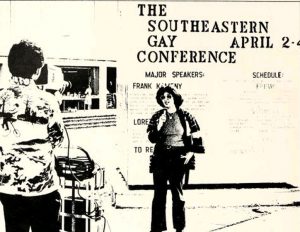

- The origins of the Carolina Gay Association in 1974 and the struggle for early LGBTQ organizations at UNC to receive recognition and support.

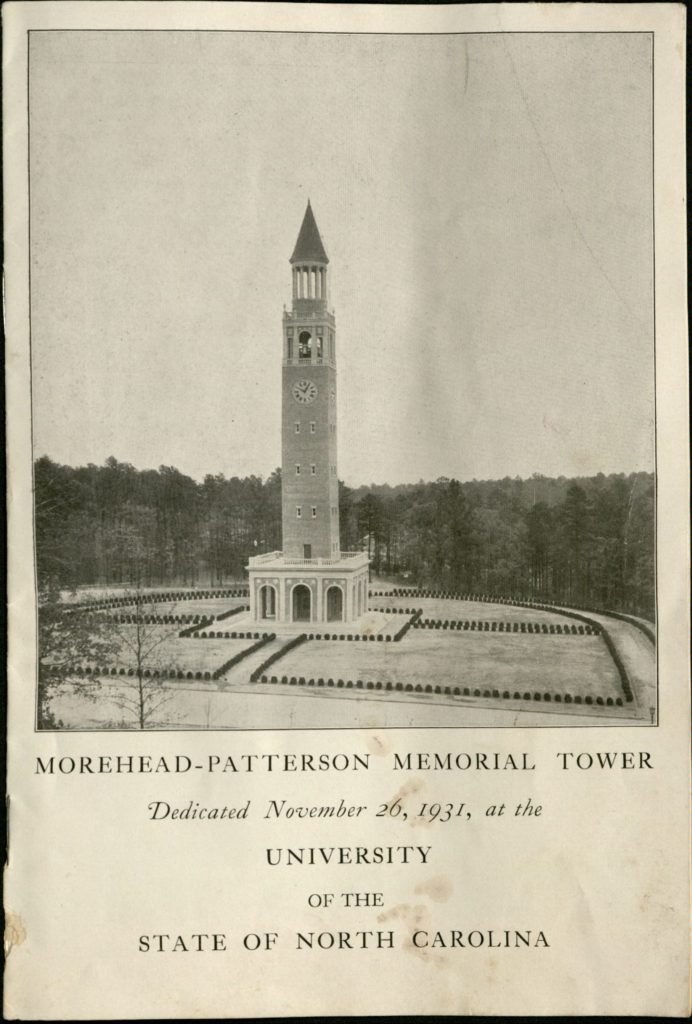

- A look at racial segregation practices on the UNC campus before and after the arrival of the first African American students in the 1950s.

- The practice of hiring slaves to use as college servants prior to emancipation.

- An examination of the different administrative policies for women students in the early to mid 20th century.