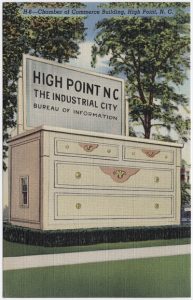

I recently came across the postcard of the High Point’s Chamber of Commerce offices, otherwise known as the “World’s Largest Bureau of Information.” It’s a linen postcard, which dates it to ca. 1930-1945. Benjamin Brigg’s 2008 book on The Architecture of High Point, North Carolina provides a good history and analysis of the building.

The building was originally built in 1926 in the shape of a chest of drawers with a mirror-like piece to highlight the city’s position as the prominent place of furniture production in the US. Molding and paint were used to create the drawers on the building’s facade, which originally featured a floral decorations, and a sheet of metal was used to make the mirror. On the inside, the walls were covered in panels of different popular woods used in High Point’s furniture industry. This outlandish design was made even more significant by its location in a highly trafficked area of downtown in Tate Park.

The card above shows the Chamber of Commerce as it looked during the inter-war period, but by 1951, the Chamber of Commerce had outgrown the original building and moved from Tate Park to a new location on Hamilton Street. The new bureau was more streamlined than the first, reflecting new trends in furniture design. The building was revamped several times during its history. The post-WWII design featured only gold trim, but the 1996 version is particularly charming, with two socks spilling out of a half-opened drawer, referencing High Point’s position in both the furniture industry and the hosiery industry.

The High Point Chamber of Commerce is a prime example of how architecture changed with American roadside culture. It’s playful, using a pun to draw a direct association between the structure and the civic department housed there – the building becomes its own sign. It also explicitly makes a statement about the social trends of furniture design as well as the city’s changing identity without using abstractions or “high art.” And both locations of the building were highly accessible (and visible) to people traveling by car.

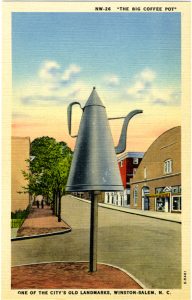

While this type of architecture became literally iconic with the rise of car culture, there are other examples that date back much earlier. For example, the larger-than-life coffee pot in downtown Winston-Salem was built in 1858 by tinsmiths Julius and Samuel Mickey to advertise their shop. It’s not a building, but it is a unique way to announce their tin shop. They huge, well-crafted tin coffee pot to speak for itself – no slogans are used, no shop hours are listed, no praises are sung.

The book Looking beyond the highway : Dixie roads and culture is an interesting collection of essays on similar issues across the South.