Historically, in places like the United States, literacy has been lawfully and socially restricted as a race-based entitlement. Written language and print culture were used in the institutionalization of European law throughout early colonial settlement territories. From the earliest days of European colonization and trans-Atlantic slavery, most enslaved Africans trafficked into the western diaspora and their descendants were intentionally kept illiterate.

During the 19th century, anti-literacy laws for enslaved people became increasingly codified and enforced in the American South in response to a fear of the social consequences of global abolitionist movements like the Haitian Revolution. Even today, decades after the Supreme Court ruling on Brown vs. the Board of Education, segregation in the American education system remains prevalent as a systemic barrier to broader tools of information literacy for the descendants of enslaved Africans.

Within Wilson Special Collections Library there are historically significant print artifacts that evidence the African diaspora’s resistance to institutionalized exclusion from the Eurocentric print culture. In honor of Black History Month, we are showcasing primary sources selected from the Rare Book Collection and the North Carolina Collection that demonstrate almost three hundred years of the history of literacy for the African diaspora in the West.

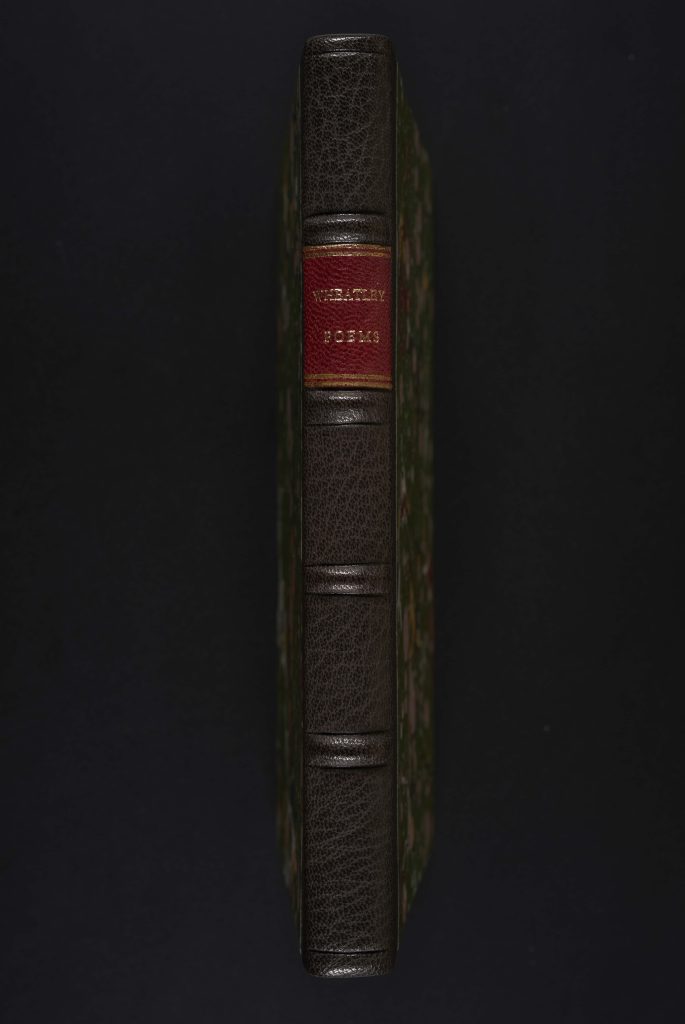

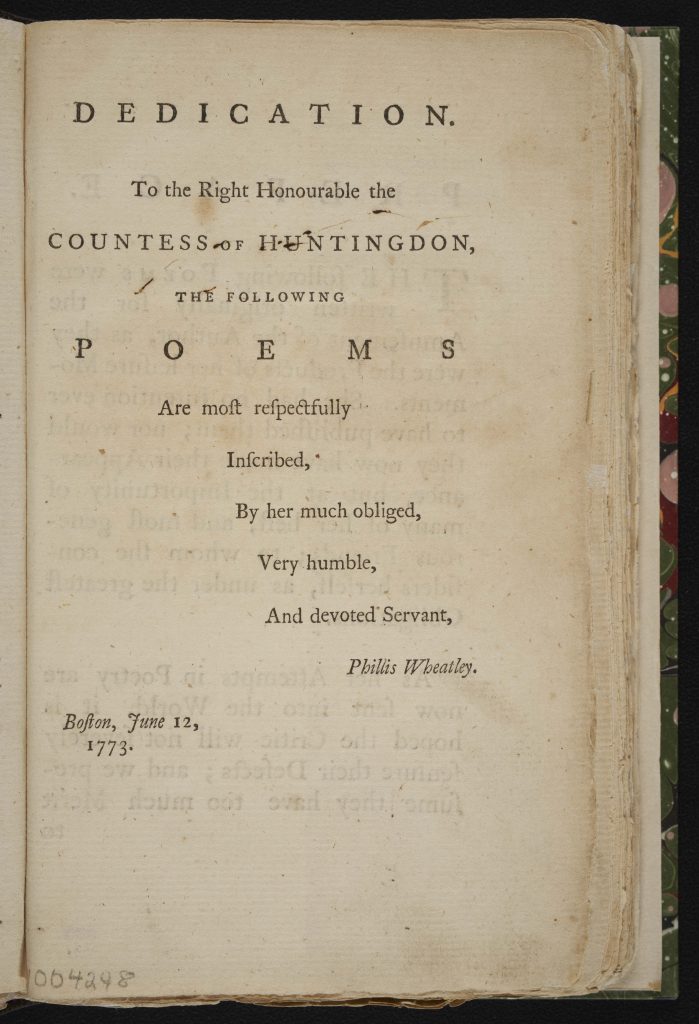

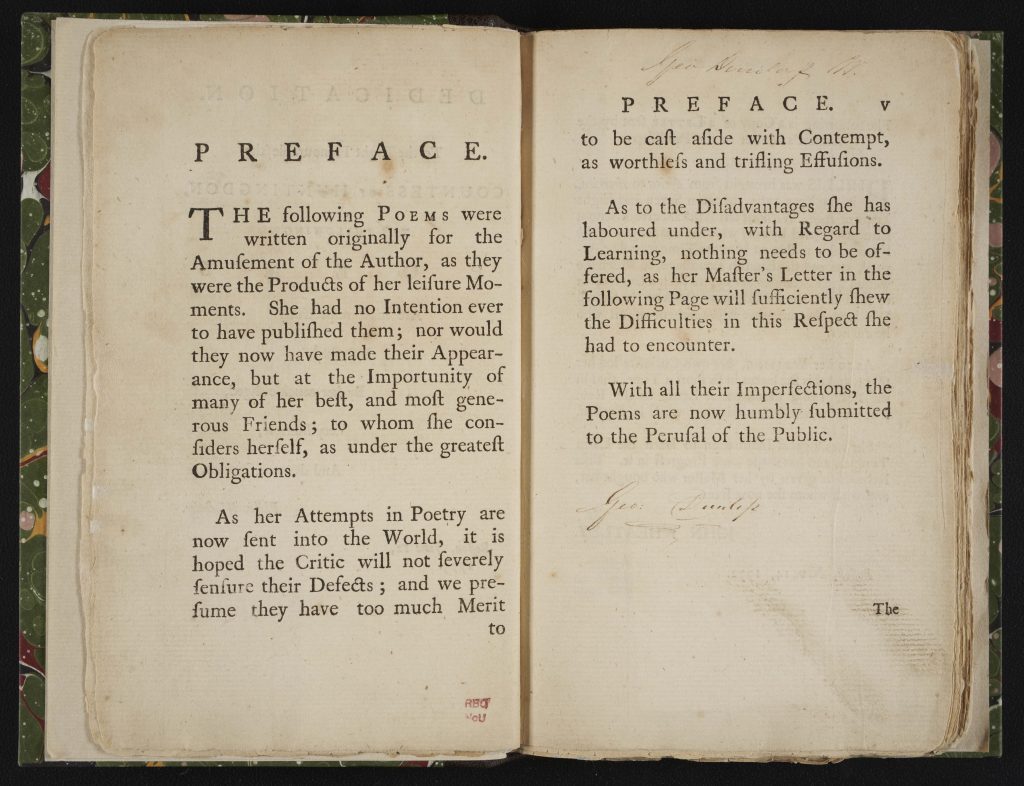

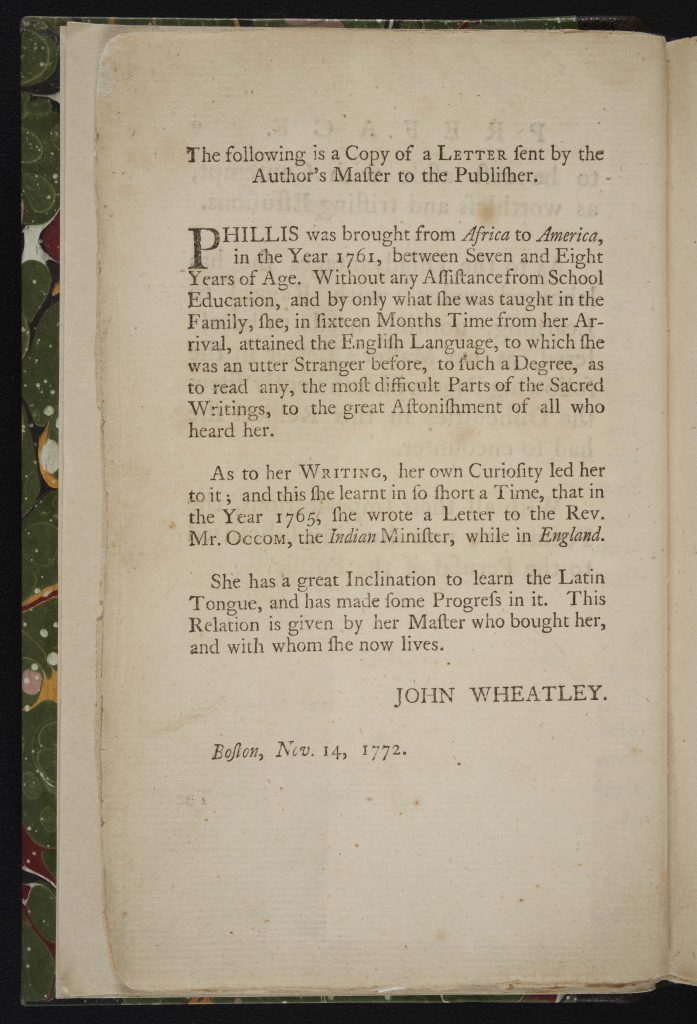

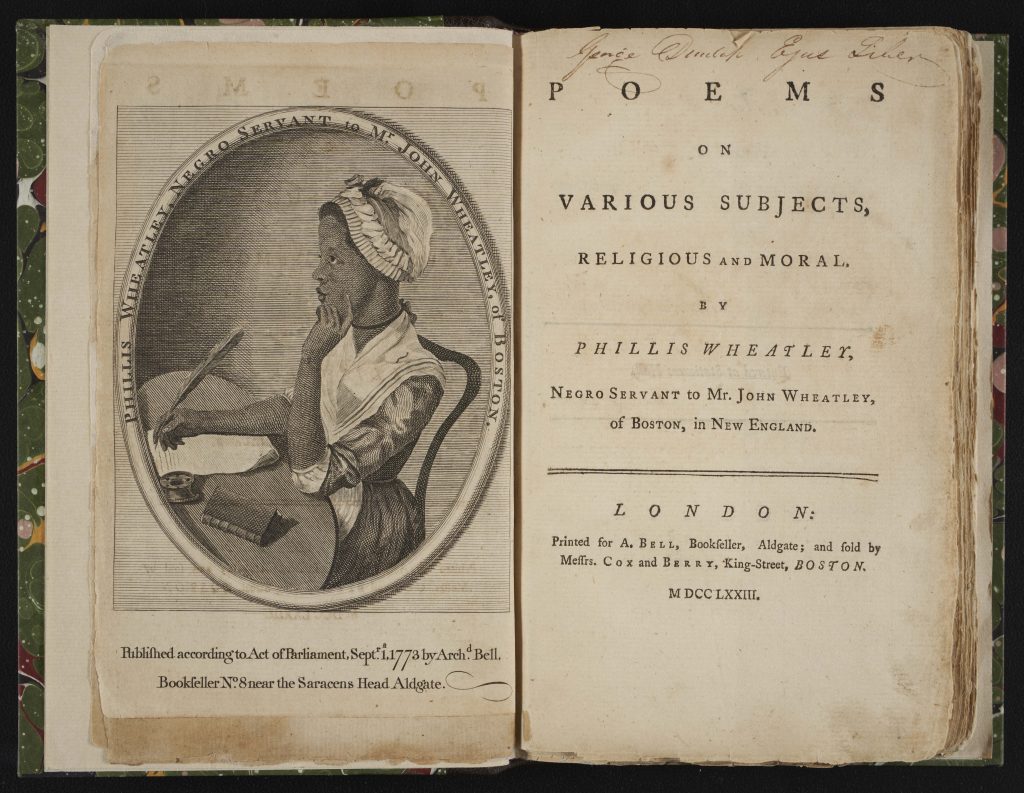

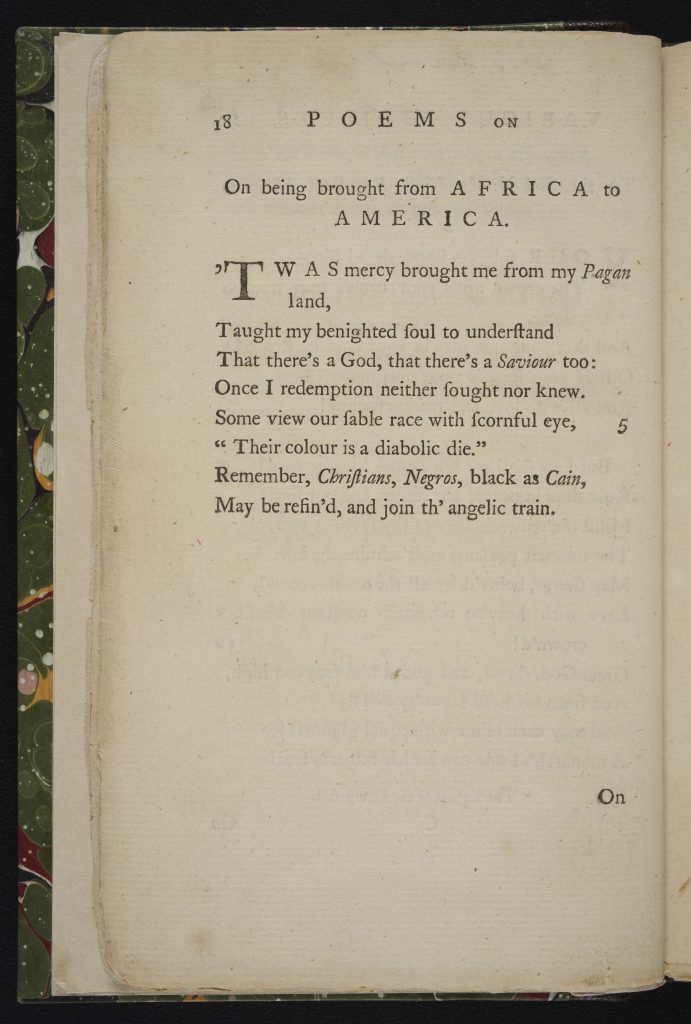

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

Phillis Wheatley, the first African American and the second woman to publish in the United States, created this work and in doing so overcame the restrictive social taboos around the literacy of enslaved persons; while not explicitly outlawed, literacy among enslaved persons in late eighteenth century Boston was unconventional. This 1773 edition of her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral is held in the Rare Book Collection. Here, the object provides a dedication; a preface; a letter by John Wheatley, who enslaved her; a portrait of the author; and a poem showcasing her unusual literacy and command of the English language.

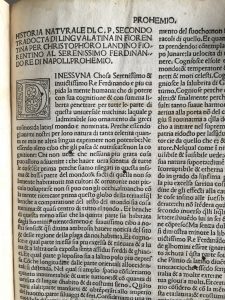

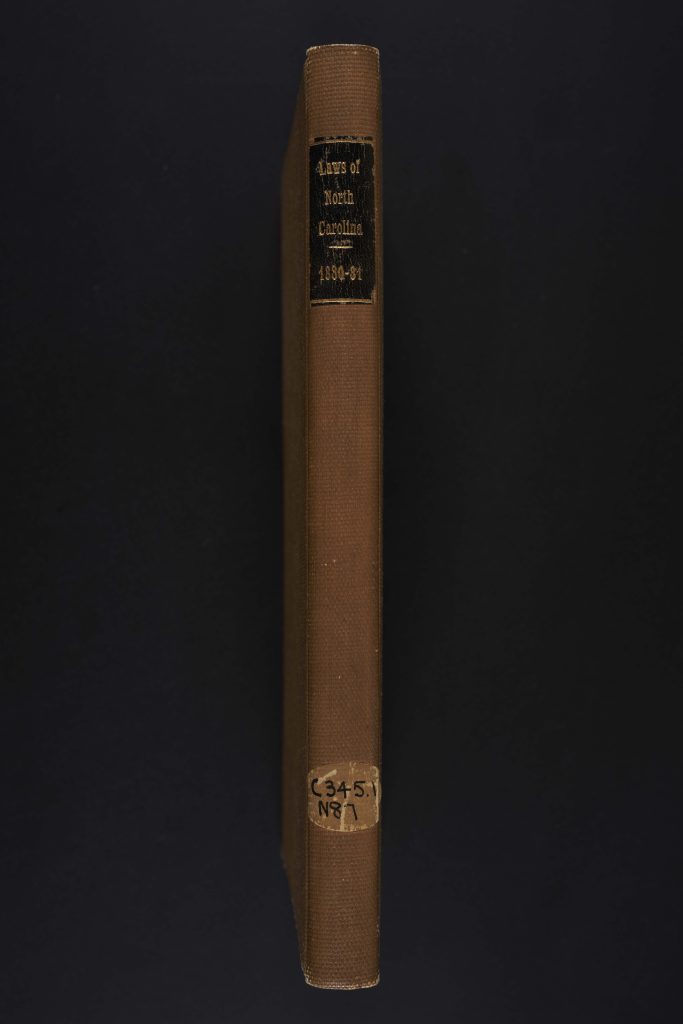

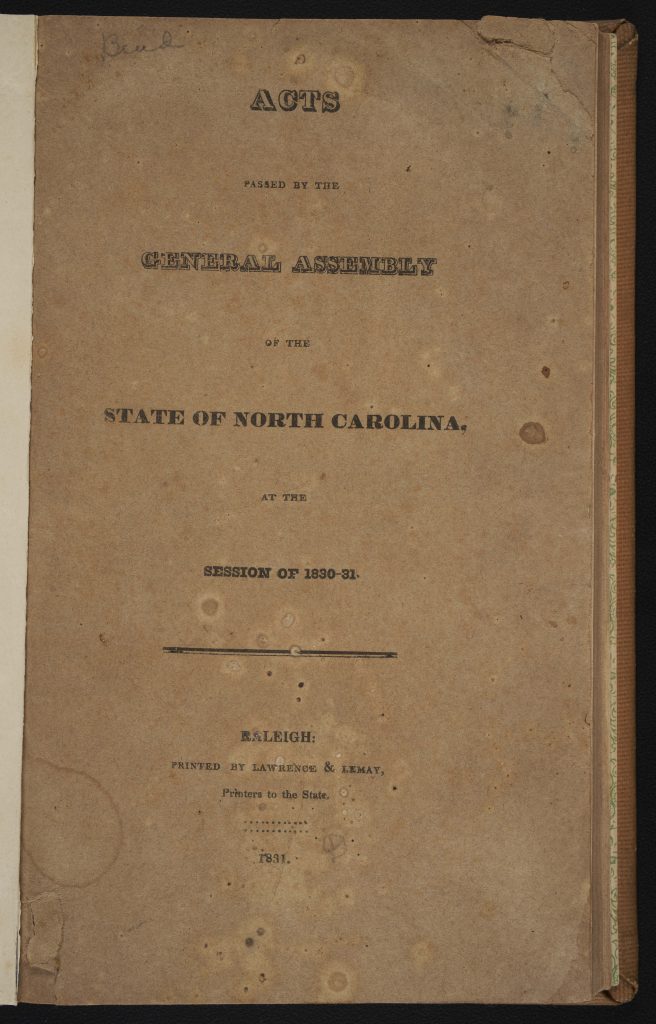

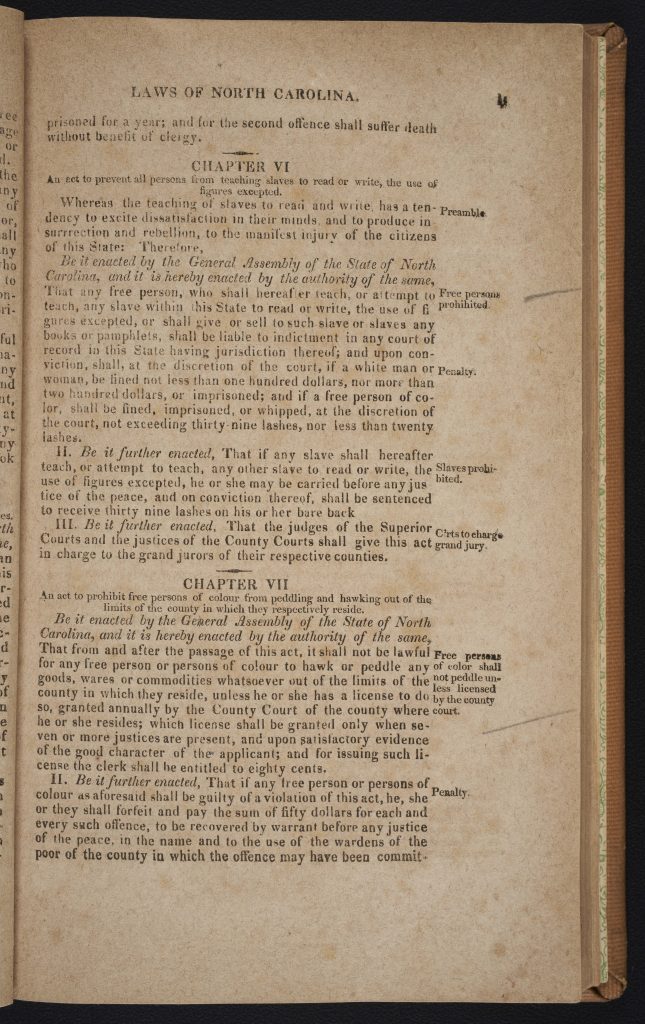

The Laws of North Carolina

Cases like Wheatly’s that evidence a history of Black literacy in the early-colonial period were anomalous. Wilson Library’s North Carolina Collection holds an 1831 edition of the Laws of North Carolina that showcases how the law was used as a tool to formally forbid the teaching of literacy to enslaved people. This object demonstrates that the right to literacy in the language of the law, indeed the very same body of law that legitimized enslavement, became a legal entitlement reserved only to those who were also afforded the legal status of whiteness.

Notably, even though formal and informal instruction of enslaved persons in literacy was outlawed in the nineteenth century, this North Carolina law shows that people who were enslaved recognized literacy as tool for claiming rights. Some used their literacy practically to communicate while navigating abolitionist communication networks like the Underground Railroad to emancipate themselves. More broadly, race-based restrictions on literacy like this North Carolina law became increasingly codified throughout the nineteenth century as lawful enslavers became fearful of retribution from enslaved peoples following the historically unprecedented success of the Haitian Revolution.

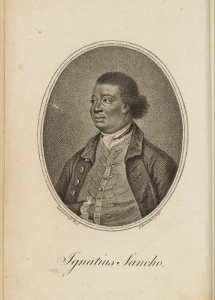

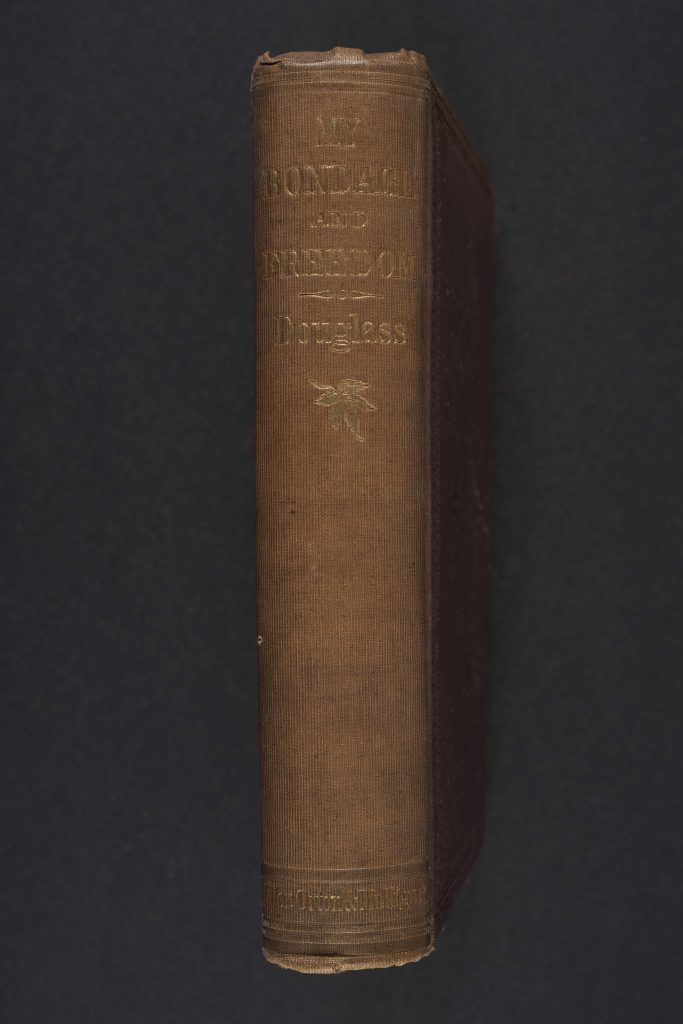

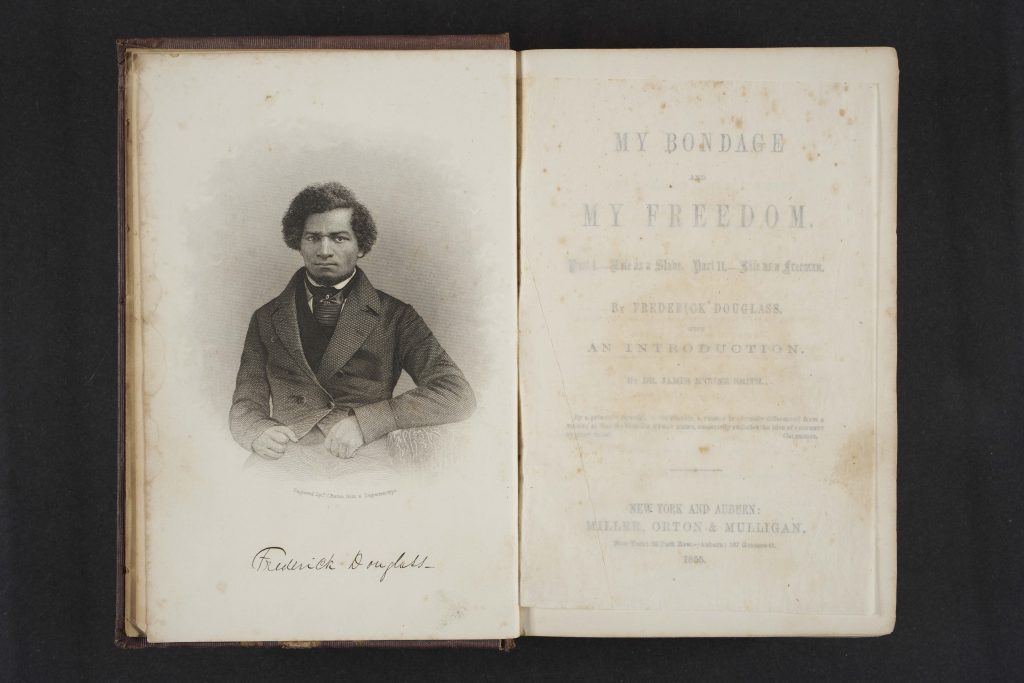

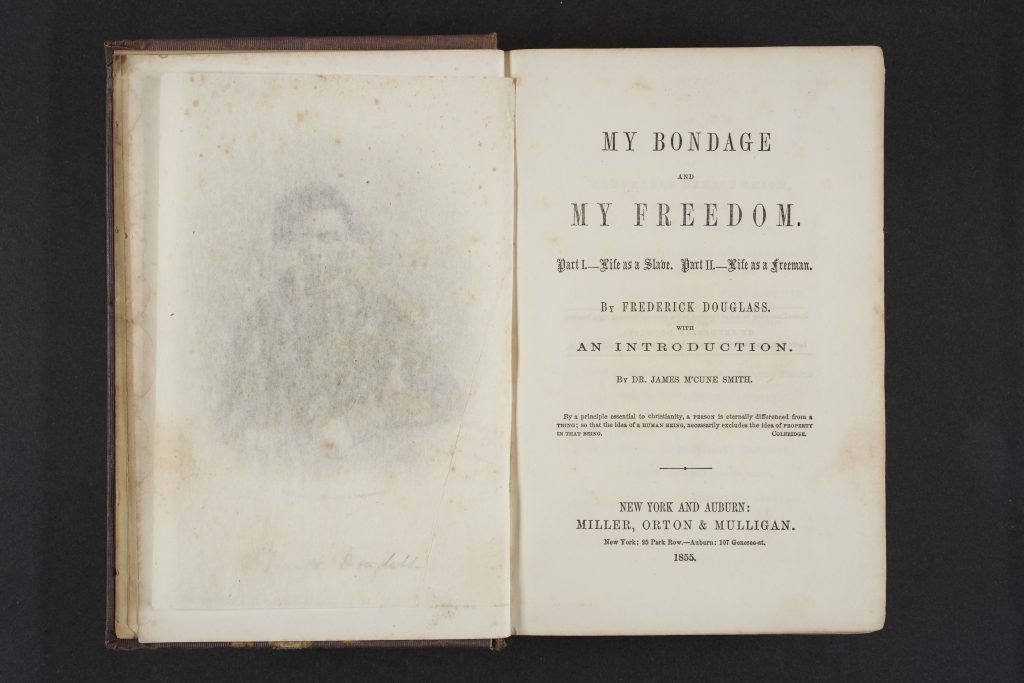

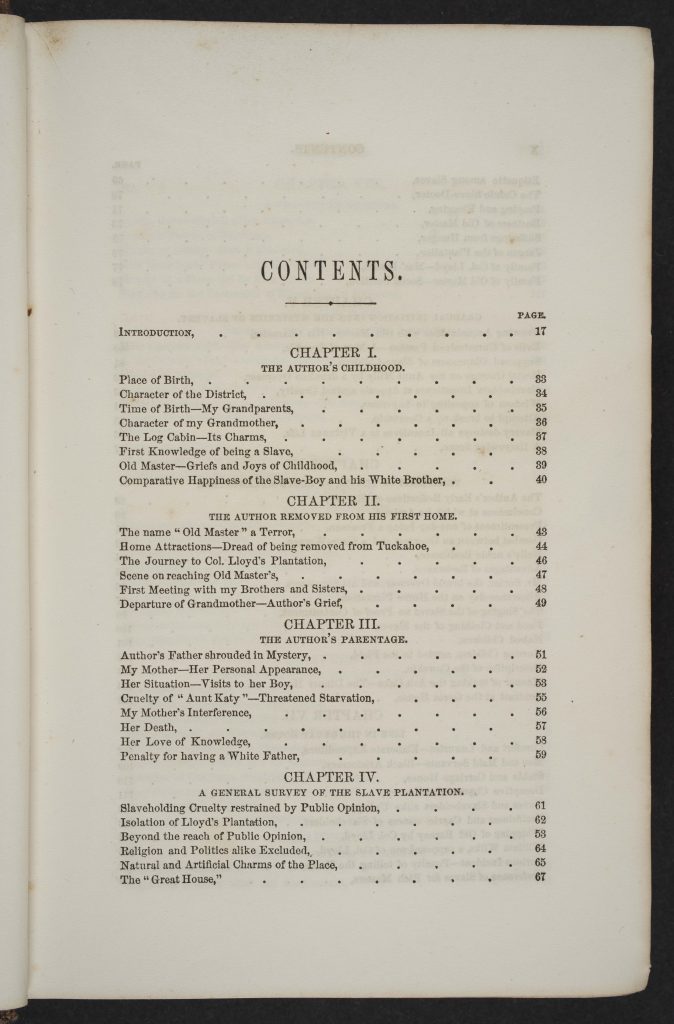

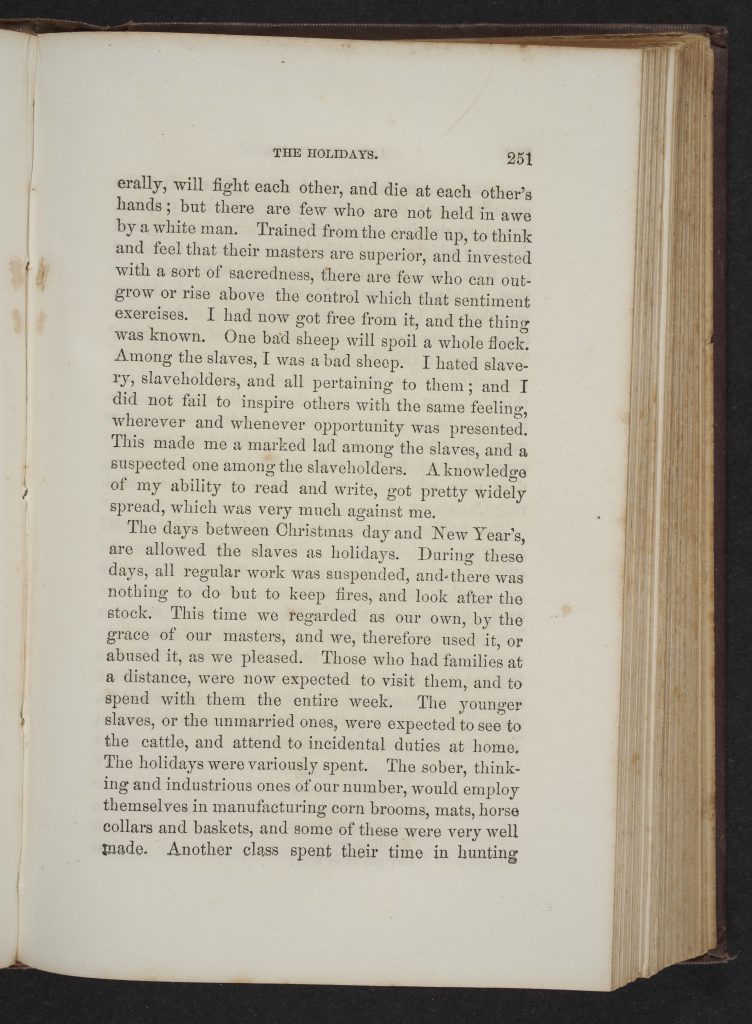

My Bondage and my Freedom

My Bondage and My Freedom by Frederick Douglass is another primary source from the Rare Book Collection that is useful for gaining insights into the history of Black literacy in the West. He escaped slavery in Maryland and went on to become an author and leader in the abolitionist movement between Massachusetts and New York, becoming one of the most famous American figures during the 19th century. This 1855 edition includes a portrait of the author. In this selection of the text, Douglass remarks on experiences he lived as an enslaved person, “A knowledge of my ability to read and write, got pretty widely spread, which was very much against me.” He notes increased ostracization from enslavers as a social consequence of his ability to inspire discontent with the conditions of lawful slavery among other members of the African diaspora.

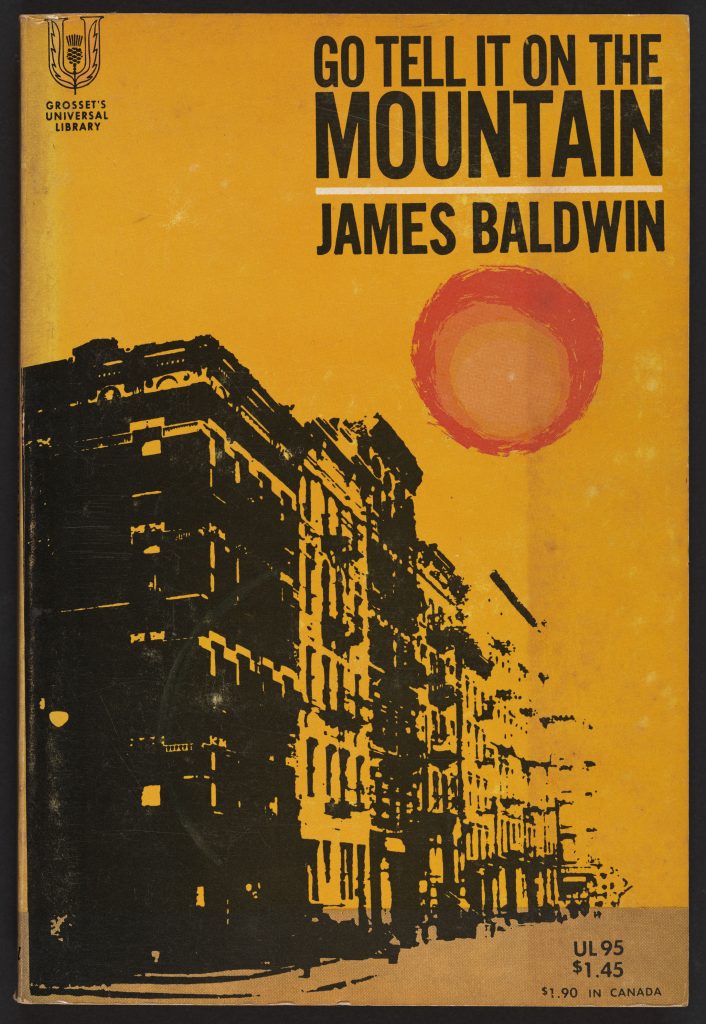

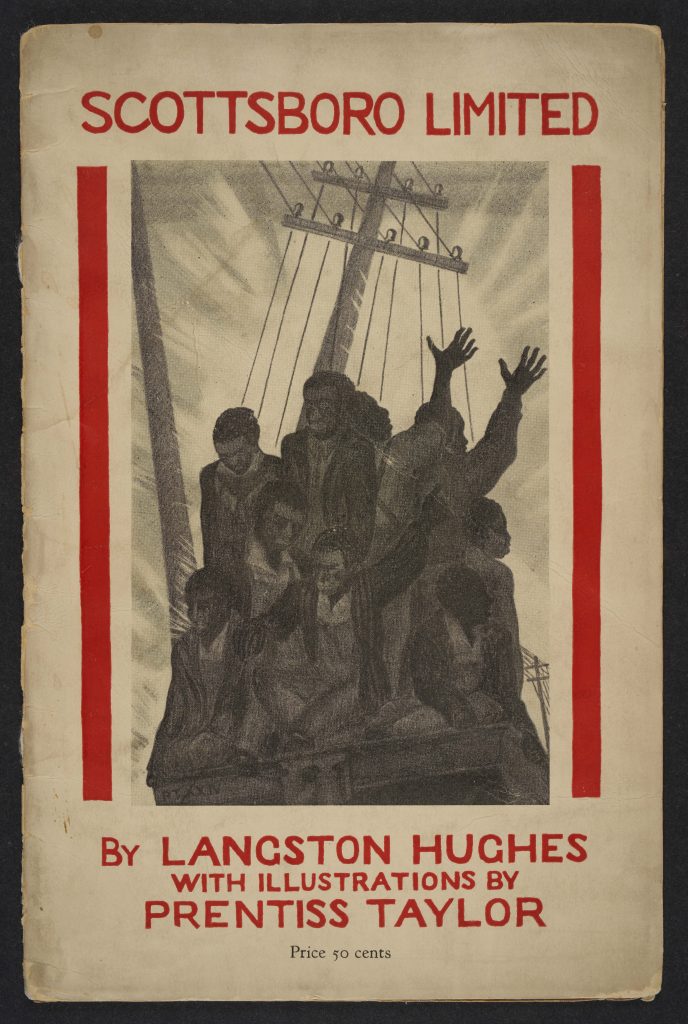

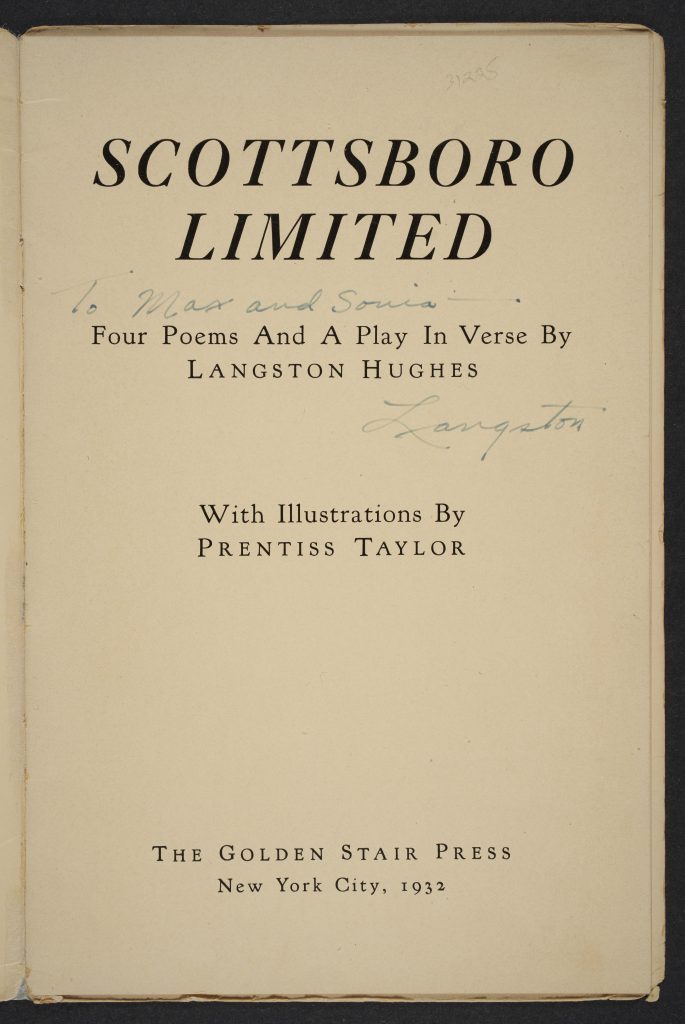

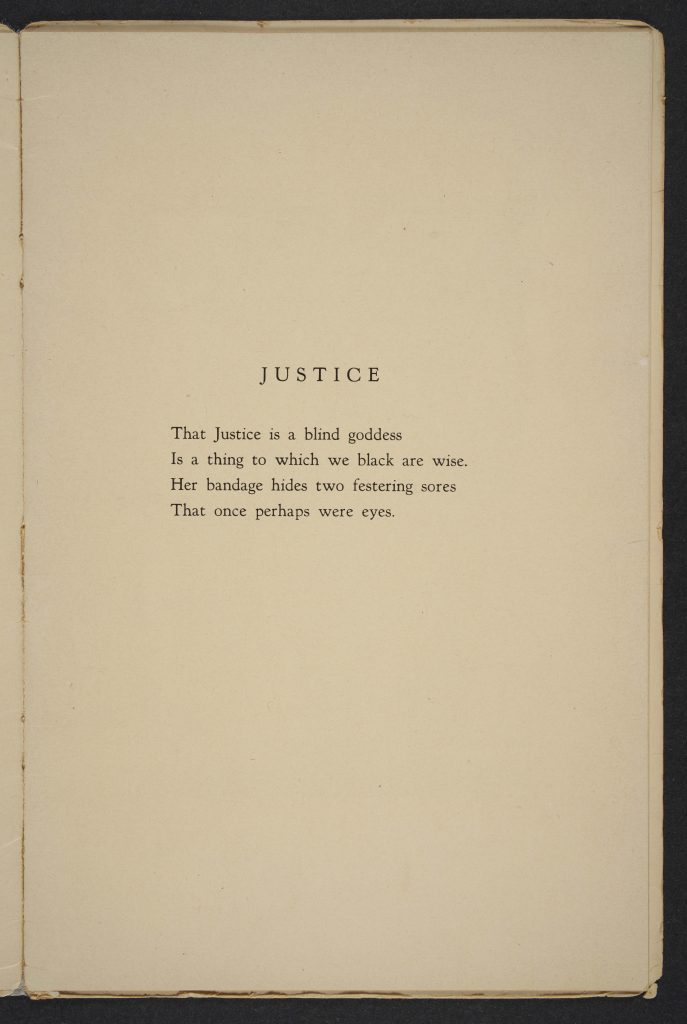

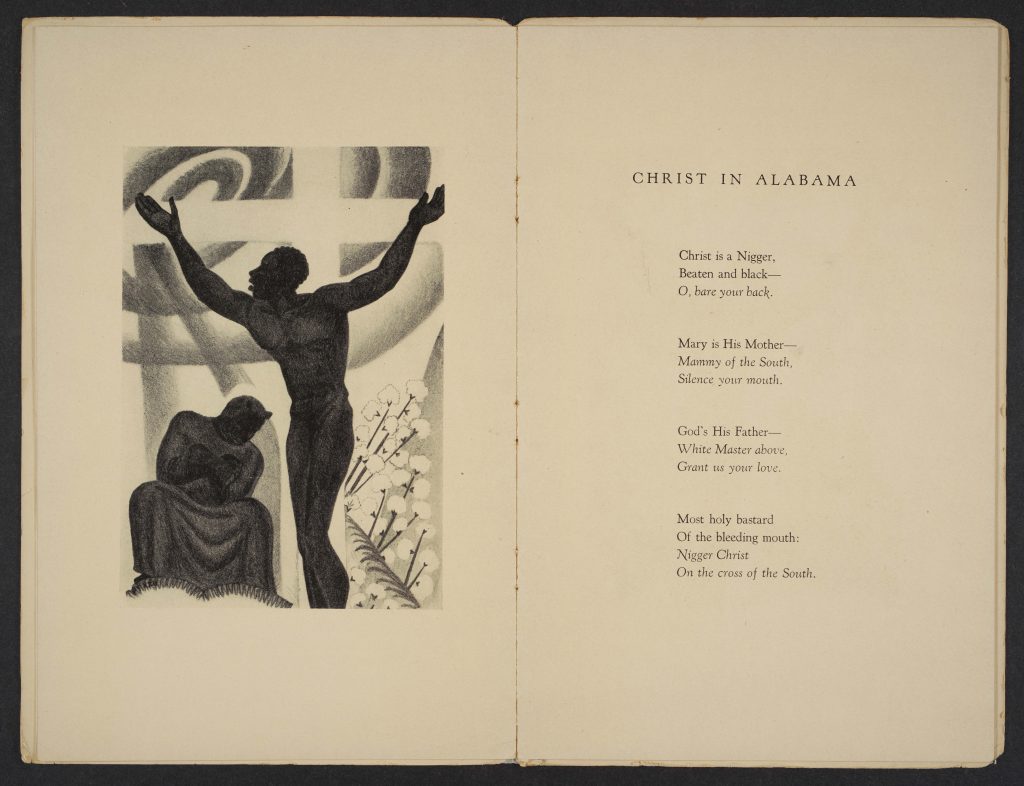

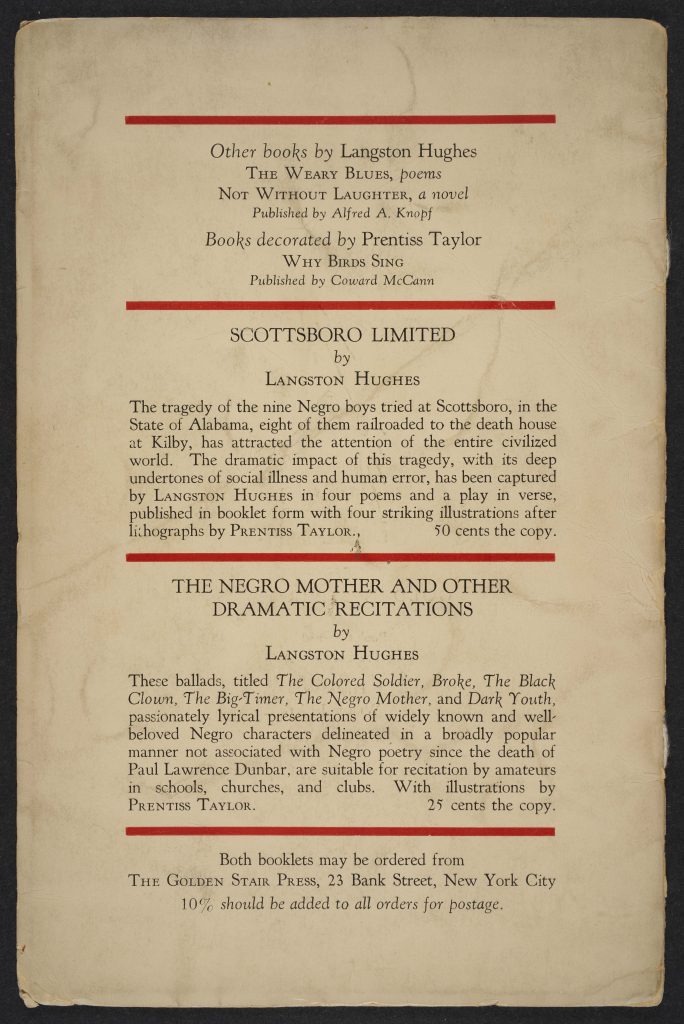

Scottsboro Limited: Four Poems and a Play in Verse

Our narrative of the history of Black literacy continues with Scottsboro Limited: Four Poems and a Play in Verse by Langston Hughes. Increased rates of literacy coincided the explosion of Black print culture that occurred in the decades following the American Civil War and the formal abolition of American slavery. The Harlem Renaissance, a cultural and intellectual revival of African American performing arts and scholarship in New York City across the 1920’s and 1930’s, was the result of increasing Black literacy. Langston Hughes, a leading figure of the movement, and here, we showcase a compilation of his works published by the Golden Stair Press into an ephemeral object. The Golden Stair Press, “was born of Langston Hughes’s desire to publish and distribute inexpensive pamphlets of poetry for African American men, women, and children- affordable literature that would be accessible in both form and content.” (Quinn, page 17). This copy includes a signature by the author and a list of other works by Hughes on the back cover.

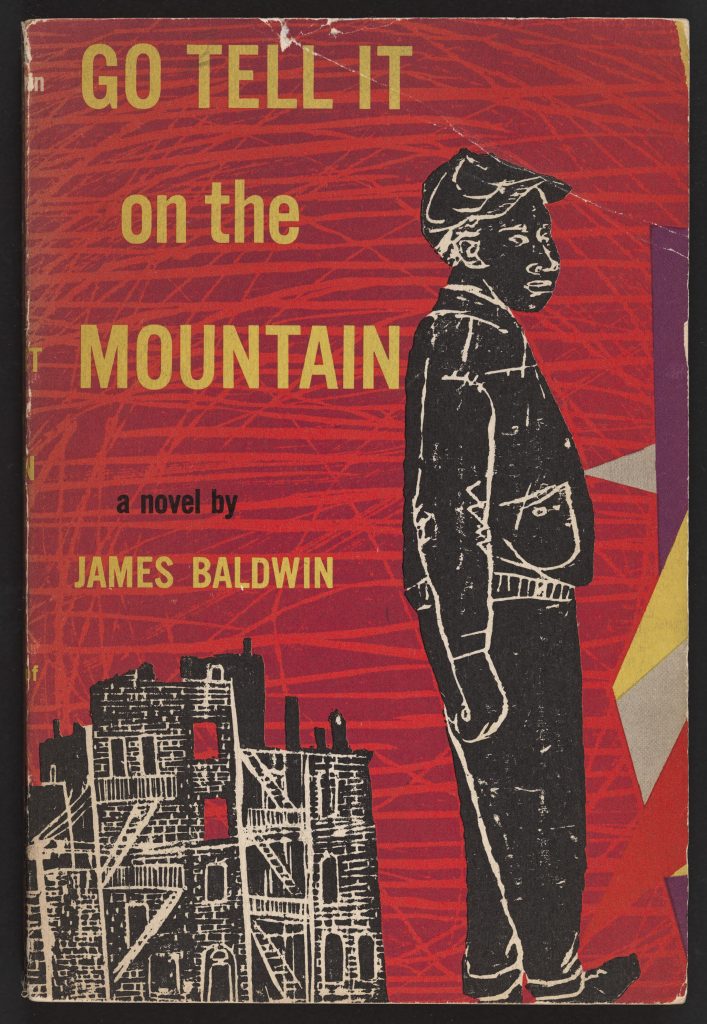

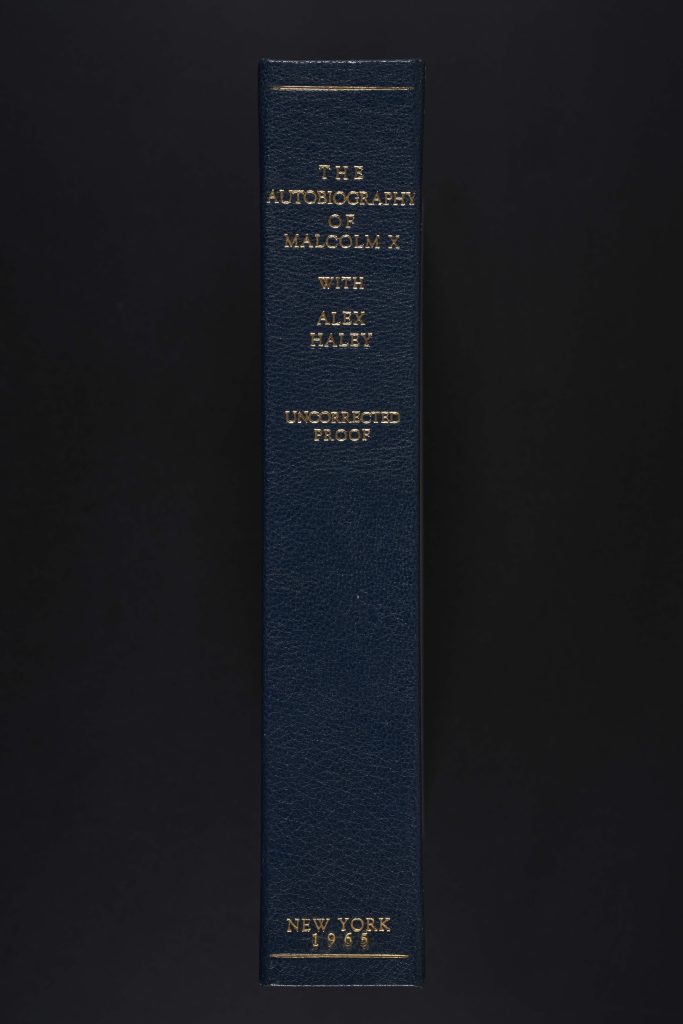

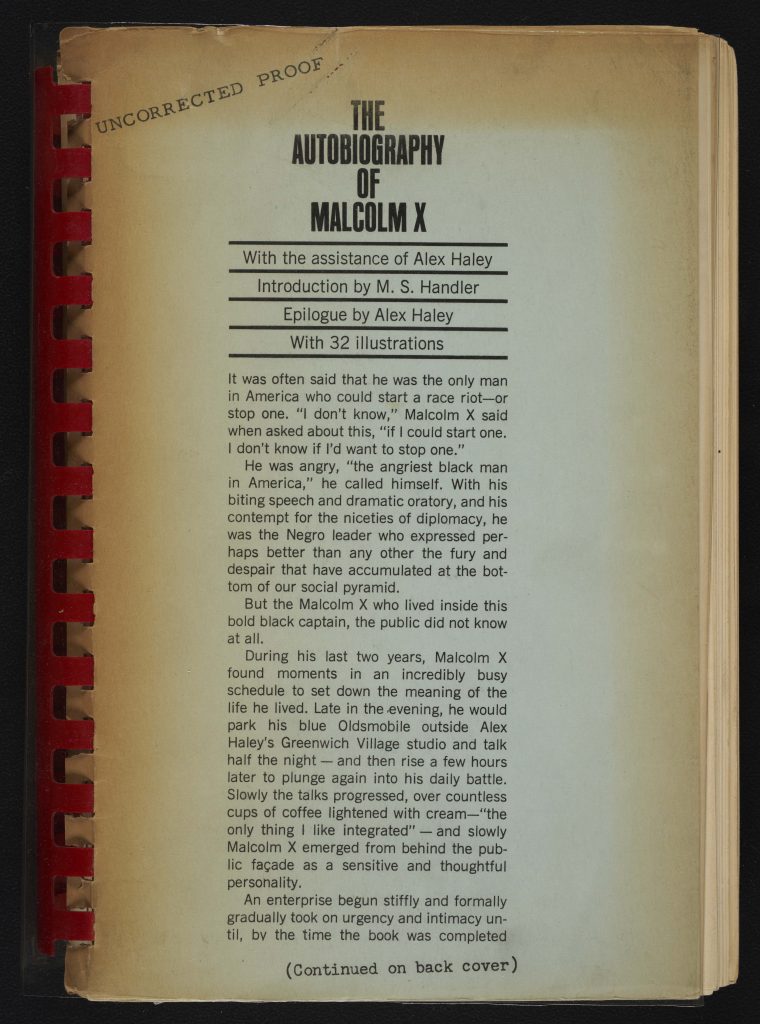

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

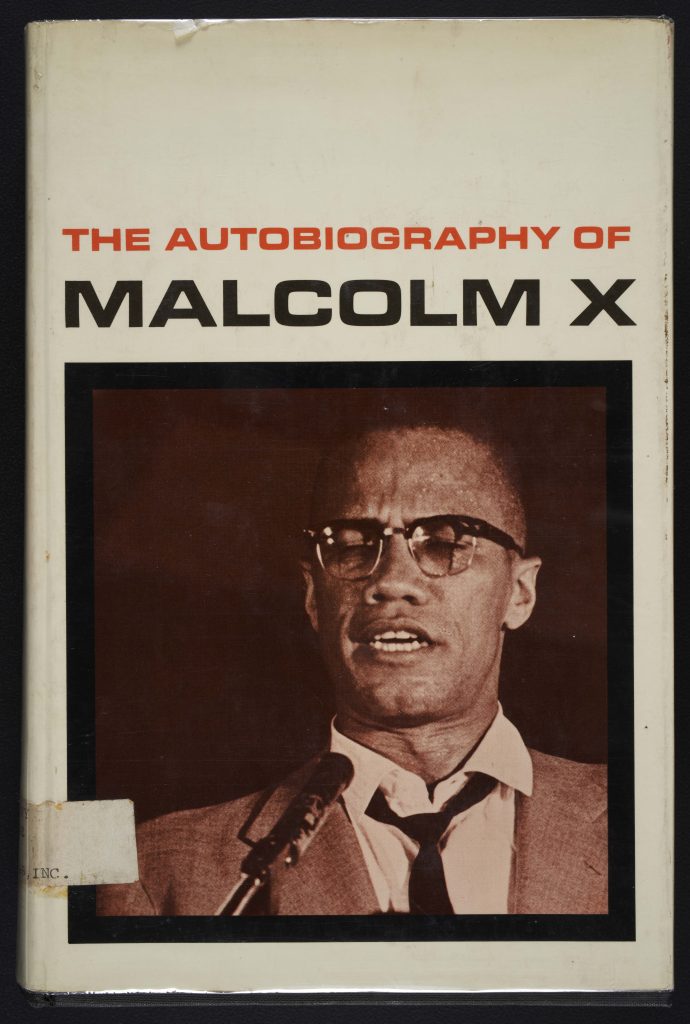

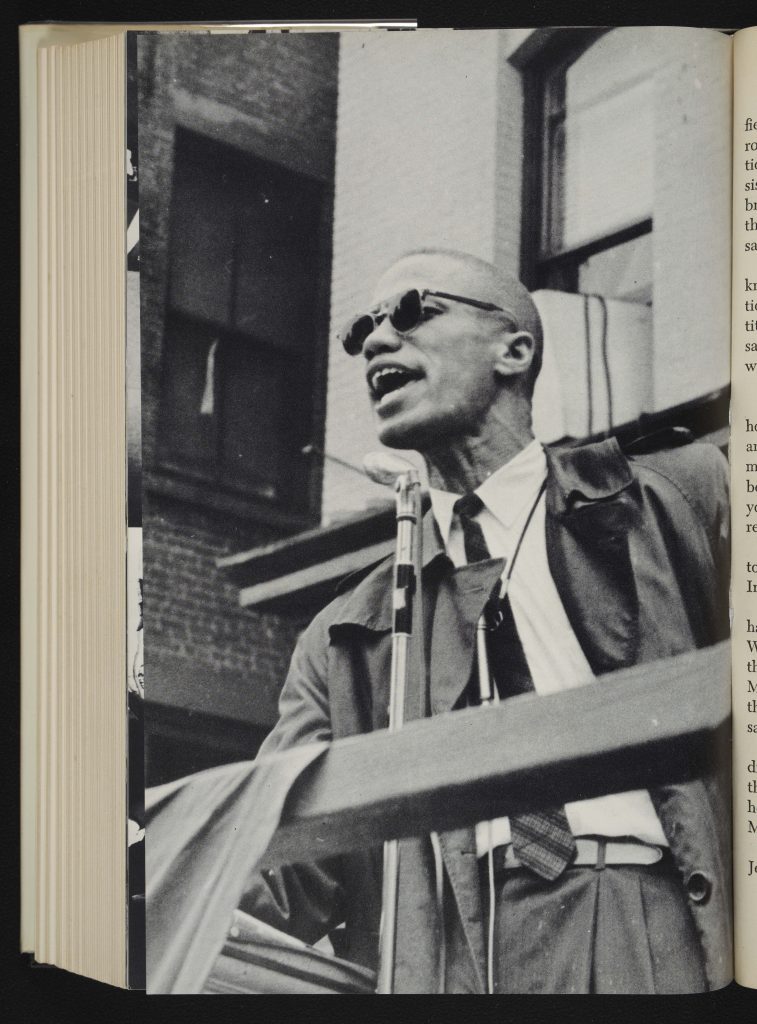

The Autobiography of Malcolm X is another primary source for showcasing the history of literacy for the African diaspora in the West. Prior to his assassination, Malcolm X dedicated his life to advocacy for restorative justice and economic reparations for slavery in Black communities around the globe. The Rare Book Collection holds two copies that are shown here. Notably, the first copy displayed is a spiral-bound uncorrected proof complete with manuscript corrections throughout. The second copy on display is a published version from 1965 that includes an authorial portrait on the dustjacket and several photographs.

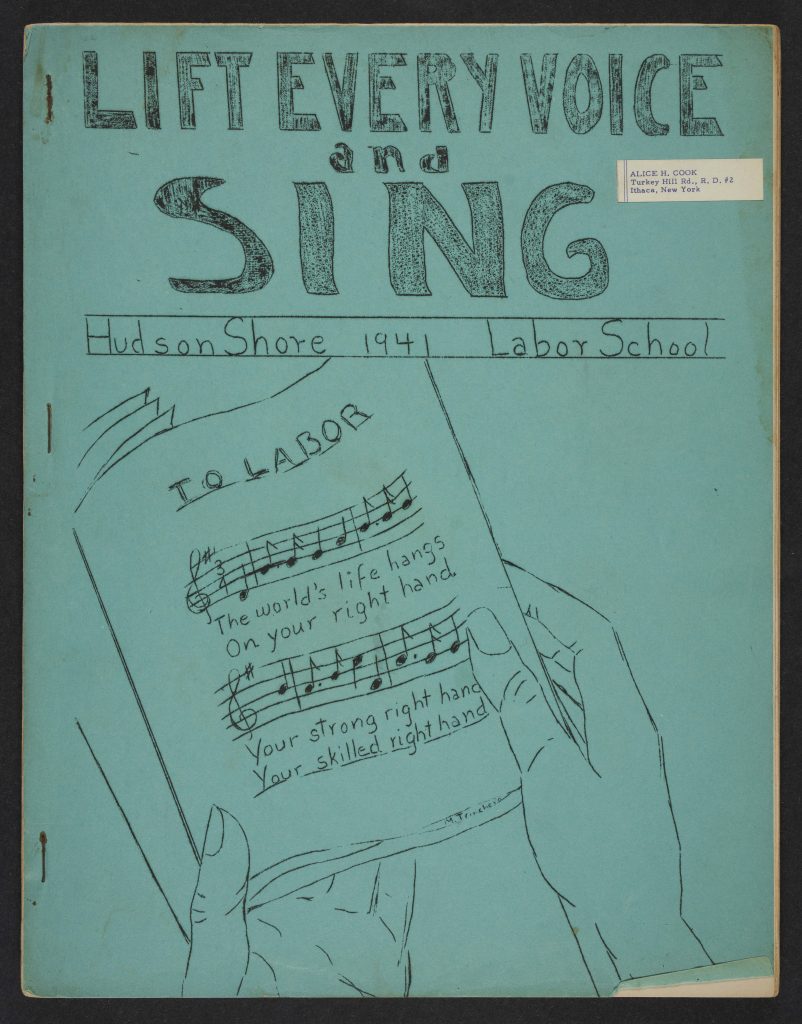

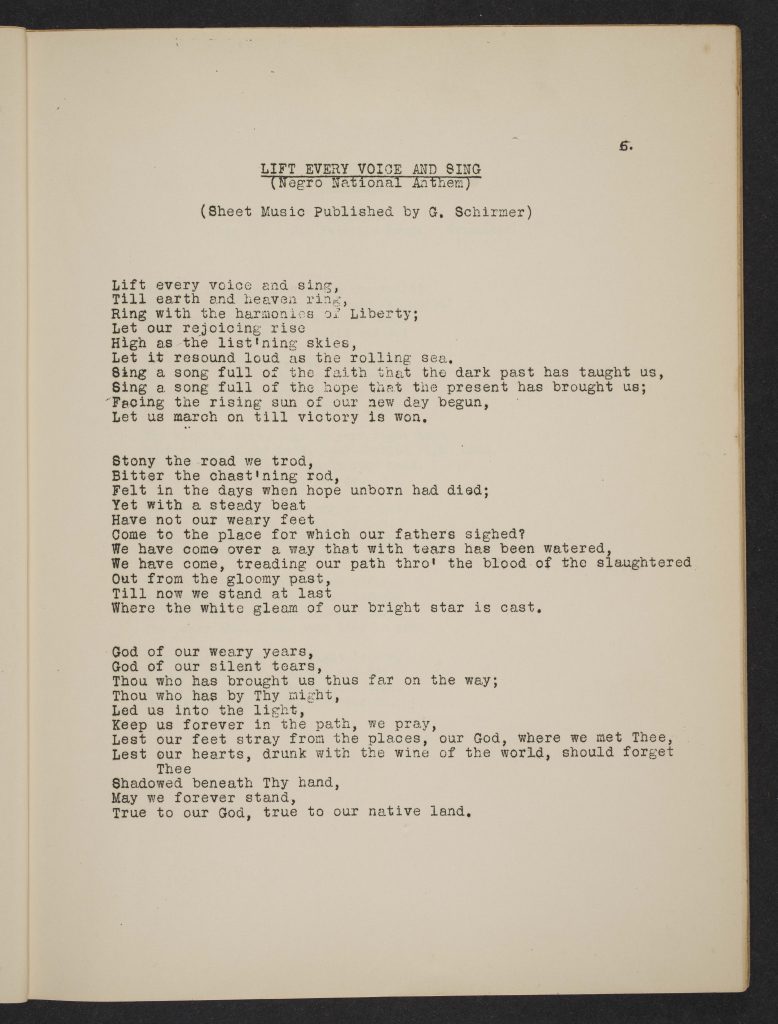

Lift Every Voice and Sing

The final object in this exhibition is a collection of songs gaining its title from the black national anthem, Lift Every Voice and Sing. The NAACP declared this song the Black national anthem in 1919. Twelve years later, President Herbert Hoover would declare the “Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem of the federal government. Here, the song is denoted as the “negro” national anthem. It is often interpreted as a song about collective hope for equality and restorative justice. In contrast, the “Star-Spangled Banner” is still the national anthem today, the third verse of which is written as,

“No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.”